Giving yourself to something you believe in, that is success.

Theodore Walter Rollins was born in New York City to a family that had immigrated from the Virgin Islands. He grew up in Harlem at a time when this crowded district at the northern tip of Manhattan was the vital center of African American culture. His politically active grandmother had been a follower of the Jamaican Pan-Africanist Marcus Garvey, who promoted solidarity among all peoples of African descent. She took a strong role in raising Sonny, as he was known from an early age, along with his older brother and sister, while their father served in the United States Navy.

Harlem in the 1930s and ‘40s was home to the latest developments in jazz, and jazz musicians were admired members of the community. Music was also an important part of life in the Rollins home; Sonny’s brother and sister studied violin and piano. The example of the pioneering rhythm-and-blues star Louis Jordan inspired the young Sonny Rollins to take up the alto saxophone. He switched to tenor sax when he fell under the spell of Coleman Hawkins, a highly sophisticated improviser who first established the tenor saxophone as a lead instrument in American jazz.

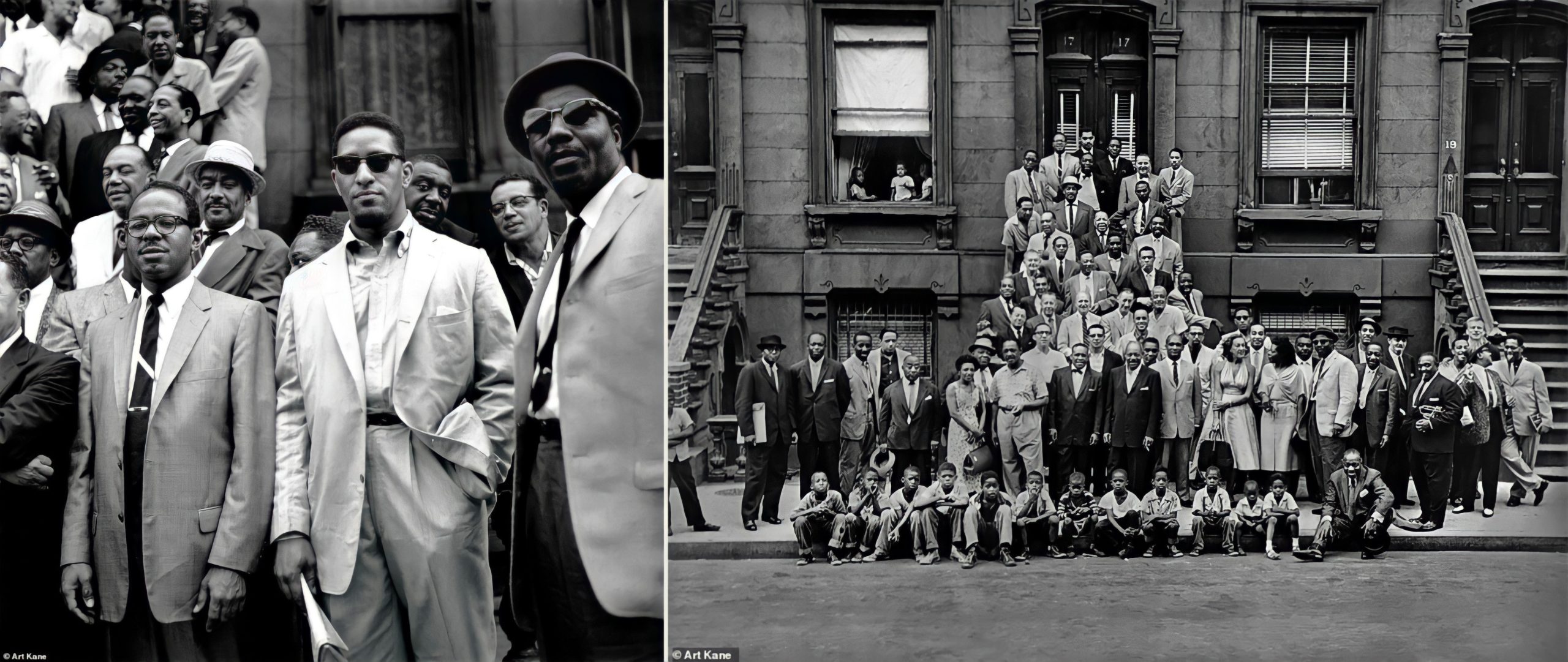

In the years following World War II, Harlem was the scene of the musical revolution known as bebop. A new generation of musicians broke with the dance-oriented big band music of the pre-war era to experiment in small groups with a new style of jazz, featuring advanced harmonies drawn from modern symphonic music, and a loose but hard-driving rhythm that provided the perfect setting for the imaginative flights of virtuoso soloists like trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie and alto saxophonist Charlie Parker. The teenage Sonny Rollins and his friends eagerly followed the new music and idolized its players, particularly the high-flying Parker, known as “Bird” to his friends and admirers. Rollins and other young musicians from his Sugar Hill neighborhood formed a band of their own, which included the gifted alto player Jackie McLean.

By age 18, Rollins had gained such a reputation that he was joining his heroes on the bandstand and in the recording studio. He made his recording debut in 1949 with vocalist Babs Gonzales. Later that year, he recorded with the virtuoso bebop pianist Bud Powell. He recorded with the innnovative pianist and composer Thelonious Monk and shared the stage with his idol, Charlie Parker. In the early 1950s he joined the band of another rising star, trumpeter Miles Davis.

Rollins’s talent was evident to everyone on the scene, but like a number of young musicians of the era, his adulation of the gifted but tragically unstable Charlie Parker had led him to emulate Parker’s drug use. Addiction led to petty crime and run-ins with the law. For a time, it appeared that a promising career had come to a premature end, but Sonny’s mother refused to give up on him. Charlie Parker himself urged Rollins to seek help before his habit consumed him. Rollins finally entered the federal rehabilitation facility in Lexington, Kentucky, where he found the treatment he needed. Freed of his addiction, he returned to New York City and embarked on a period of staggering productivity.

In 1955, Rollins joined a quintet led by pioneering bebop drummer Max Roach, also featuring the gifted trumpeter Clifford Brown. In addition to recording under Max Roach’s name, the quintet produced an album as Sonny Rollins Plus Four, the first collection to feature Rollins as leader. The untimely death of Clifford Brown in a 1956 automobile accident was a blow to the entire jazz world. Rollins stayed with the Roach quintet through this difficult transition, but he was soon producing recordings of his own at an extraordinary pace.

Max Roach supported the younger man’s efforts, playing drums on Rollins’s album Sonny Rollins, Volume One. In the follow-up collection, Volume Two, Rollins was joined by two great pianists: one of the original architects of bebop, Thelonious Monk; and the leading proponent of the new “hard bop” style, Horace Silver. Rollins was now a leading jazz star. The album, Saxophone Colossus, introduced his signature composition, “St. Thomas,” based on a traditional calypso his mother had sung to him in childhood. Major collections from Rollins in this period include the albums Tenor Madness — featuring him in a duet with an up-and-coming rival on the tenor, John Coltrane — and Newk’s Time. A number of Rollins’s friends had taken to calling him “Newk” because of his supposed resemblance to Brooklyn Dodgers pitcher Don Newcombe.

Two hallmarks of Rollins’s career were now well in evidence. One was his penchant for “thematic improvisation,” in which the soloist performs a series of spontaneous variations on a single musical idea. Another was his affection for familiar popular songs and show tunes that other young musicians of the day had come to disdain. Rollins seemed to delight in showing that no melody was so shopworn that it could not be mined for new improvisational riches. A number of outstanding live recordings followed these studio sessions, including A Night at the Village Vanguard, which show Rollins in extraordinary form, supported only by bass and drums. This piano-less saxophone trio was a new concept in jazz. With no piano providing harmonic support, Rollins found unexpected melodic byways that lay beyond conventional harmonic structures.

As the 1950s drew to a close, Sonny Rollins was the most admired, talked-about, sought-after tenor player in jazz, the biggest sax star since Charlie Parker. But Rollins felt this acclaim was undeserved, that his playing did not meet his own high standards. At the height of his fame, he withdrew from public performance and recording. He remained in New York City, and found a congenial place to practice on the Williamsburg Bridge spanning the East River, not far from his home on the Lower East Side. Musicians and neighbors were surprised to find the one-time headliner standing on the bridge at all hours, playing for no one but himself, while he honed his technique and searched for a more spiritually meaningful form of musical expression.

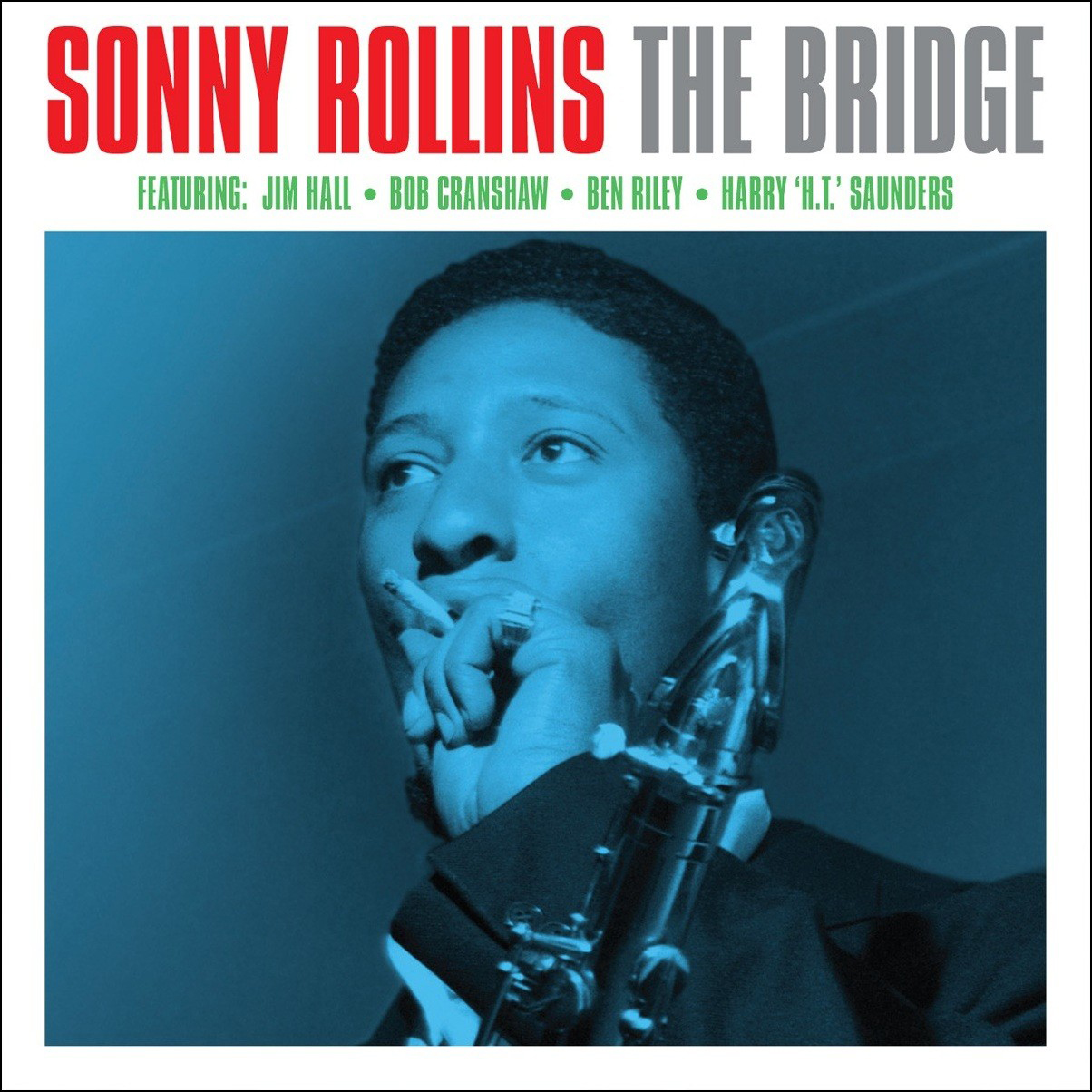

While Sonny Rollins took his sabbatical, revolutionary changes were again shaking the jazz world. He emerged from his three-year exile with a strengthened technique — demonstrated on his comeback album, The Bridge — ready to adapt to all of the innovations that had taken place in jazz during his absence. Throughout the 1960s, Rollins met the challenge of every new development head-on, participating in the avant-garde and “free jazz” experiments of younger musicians, and finally recording with his childhood hero Coleman Hawkins. During this eclectic phase of his career he performed Latin jazz, recorded an album of standards, and composed a popular soundtrack for the 1966 hit film Alfie, starring Michael Caine.

Toward the end of the ‘60s, Rollins took another break from his musical career to immerse himself in the study of Eastern religions. For a while he lived in Japan, then traveled to India, where he studied yoga and spent a long retreat meditating in a monastery. By the early ‘70s, he was ready to return to active recording and performing. His spiritual journey had brought peace to his restless soul, and he addressed his audiences with a new sense of joy and acceptance. He found continued inspiration in traditional Caribbean melodies, and embraced the use of electric instruments and the rhythms of contemporary funk and R&B. These adventures led him into musical territory far from the hard bop of his youth. He startled both jazz and rock fans with an unexpected appearance on the 1981 Rolling Stones album, Tattoo You.

In addition to his work with large electric groups, he pursued the opposite extreme, performing as a solo artist without accompaniment of any kind. In this setting, his solos took the form of long, stream-of-consciousness monologues, drawing on his seemingly bottomless repertoire of classic songs. This side of his creative personality was reflected on his 1985 recording, Solo Album. His solo performances scaled heights of inspiration that transcended all considerations of style and genre, and brought him some of the greatest acclaim of his career.

Rollins was at home in Manhattan, not far from the World Trade Center, when his native city was attacked on September 11, 2001. Only a few days after the catastrophe, Rollins recorded a live concert, Without a Song: The 9/11 Concert, as a tribute to his fallen neighbors. Other releases from this period include Road Show, Volume 1, a compilation of some of his most dynamic live performances from the previous 30 years.

The publication of a new biography of Sonny Rollins, Saxophone Colossus, by John Abbott and Bob Blumenthal, was timed to coincide with his 80th birthday. Other celebrations included a gala concert at New York’s Beacon Theatre.

At age 82, Sonny Rollins played his last concert, his powerful tone finally silenced by pulmonary fibrosis. He retired to Woodstock, New York, to spend his declining years in spiritual pursuits, and to oversee continued releases from his vast archive of recorded performances.

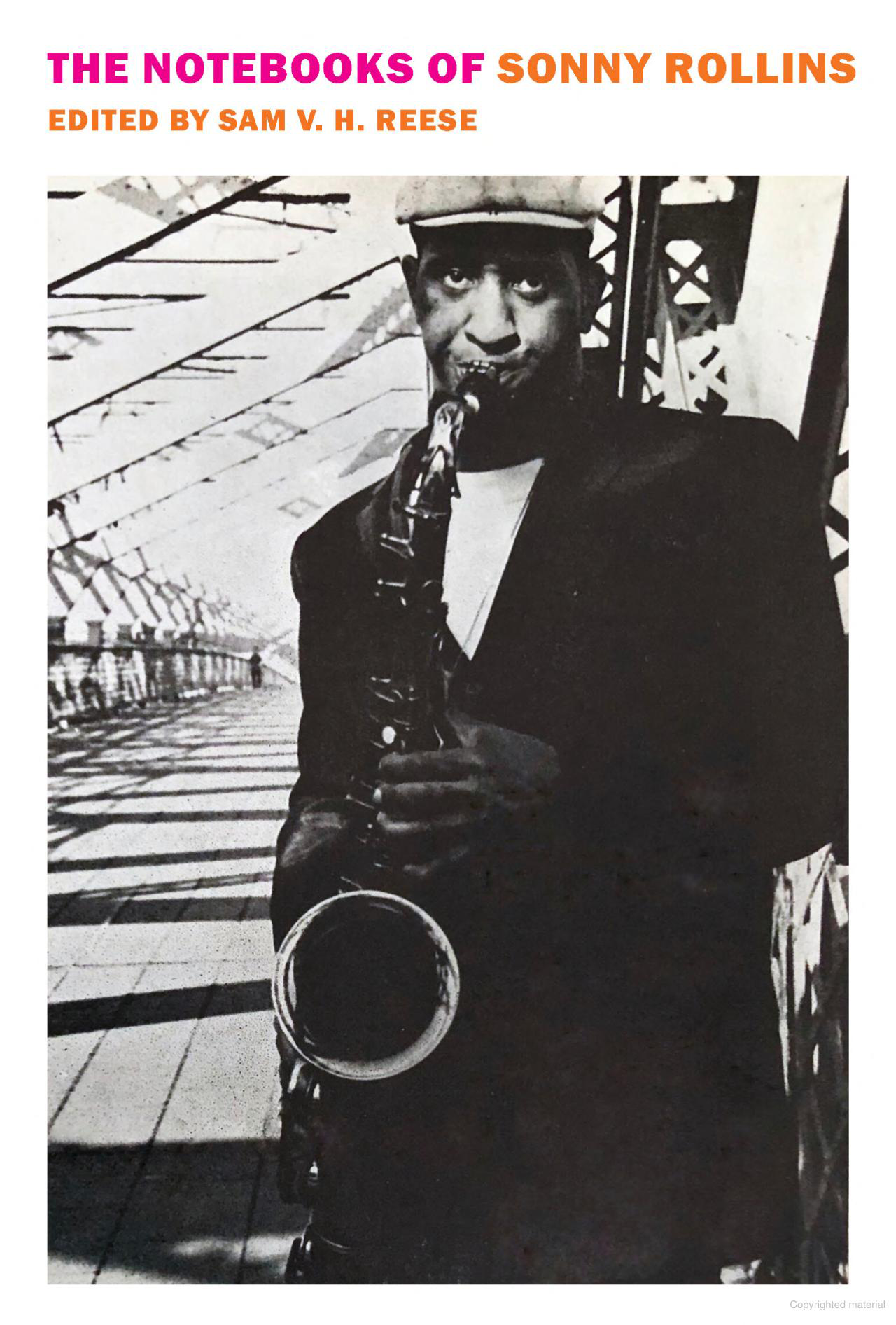

The Notebooks of Sonny Rollins, edited by Sam V.H. Reese, was released on April 16, 2024, and offers a profound glimpse into the jazz icon’s mind. This book, based on Rollins’s writings during his sabbatical on the Williamsburg Bridge from 1959 to 1961, explores music theory, daily routines, spirituality, and systemic racism. Rollins studied the physics and physicality of music, aiming for the “instantaneous creation of music”—a seamless link between thought and sound, filled with emotion. His reflections echo Emerson and Thoreau and highlight the interconnectedness of all music, from Bach to Miles Davis. This collection provides deep insights into the mind and workshop of a musical titan, offering both inspiration and wisdom.

Sonny Rollins performs an improvisational duet with tap-dancing legend Savion Glover at the 2006 International Achievement Summit in Los Angeles, to an audience of Academy youth delegates, Council members, and fellow Golden Plate awardees.

The last survivor of the generation of giants who revolutionized jazz in the 1950s, Sonny Rollins played and recorded with Charlie Parker, Miles Davis and Thelonious Monk while still in his teens. By the end of the decade, he reigned supreme as the most talented and innovative tenor saxophonist in jazz. Rather than follow the easy path to commercial success by repeating his past performances, he left the stage for three years at the height of his fame to practice alone on New York’s Williamsburg Bridge, single-mindedly pursuing his own elusive ideal of perfection. Throughout his career he took leaves of absence for travel, study and meditation, always to return with a new approach to music.

He recorded in a dazzling variety of styles, from the hard bop of his youth to the free jazz, avant-garde, fusion, Latin jazz, funk and R&B of subsequent decades. A formidable composer and bandleader, he was unparalleled in his imagination and expressiveness as a soloist. Armed with a devastating technique and an encyclopedic knowledge of popular song, he held audiences spellbound with a seemingly endless flow of melodic invention.

A 1956 album title still captures his enduring stature in the world of jazz: Saxophone Colossus. Rollins continued performing into his ninth decade, before retiring to a life of spiritual contemplation. His legacy of recordings remains an inspiration to music lovers and seekers of transcendence.

How would you describe the life of a jazz musician?

Sonny Rollins: The life of a jazz musician is a very precarious life. A good friend of mine, a pianist who has got a good reputation, he just had sort of an altercation, and he was hurt. Jazz musicians, they want to express everything, and their life is sort of right out there on their sleeve, but we live in a world in which you can’t always be that way. Playing is great, but you can’t live your life like you’re on the bandstand. You have to live a different life when you are off the bandstand. You have to be a little more conformist, and most jazz musicians find that difficult. Artists find it difficult to be a more normal person when they are off the bandstand.

The life of a jazz musician is a difficult life, because you want to play, you want to be, you want to get to the inner spirit and sometimes you drink or you use drugs or you smoke a lot. You do all these things to try to get the spirit out. So it’s a difficult existence and a lot of the great people that I have known, and in history, they kind of over-indulge, and they never sort of are able to balance their musical life with their personal life. Maybe it’s not necessary to do that. That is another question, I don’t know, but I’d like to see young musicians coming up that don’t smoke and that don’t drink to excess and don’t use drugs, and don’t sort of debilitate themselves. I think that’s where we should go. I think that is what guys should be doing. I don’t think you have to drink and use drugs to play good jazz, but that’s been the model for so long that a lot of guys get caught up in that, you know.

Early in your career, you encountered great success and recognition, but you also experienced some of these problems — drugs and prison. Can you talk about that?

Sonny Rollins: I used to be reticent about talking about that, because it was always like, “Well, let’s stigmatize this jazz musician. Let’s talk about, Oh, he’s a criminal.” But my wife, my dear departed wife used to tell me, “Well, no, Sonny, don’t be afraid. Don’t not want to talk about it, because after all, you have been through it, you came through it, and it’s a great experience. You have conquered it, so to speak.” So I don’t mind talking about it now.

Sometimes I wonder why I am asked that.

It’s important to understand the kind of obstacles people have to overcome to come out on the other end and achieve something great, as you have. That’s the only reason.

Sonny Rollins: Well, that was the rationale actually, not to be ashamed about it. Most people might ask for the same reason, but people that are involved are super-sensitive, perhaps, anyway. But anyway, yeah, I got involved.

We were following our idols. Charlie Parker. And we were told Billie Holliday used drugs, and all this stuff. But my main influence — our main influence — was Charlie Parker; he was our messiah. And Charlie Parker used drugs, so all of us figured that, “Oh, if he used drugs, it’s okay.” But it wasn’t okay, because guys drop through the holes, you know. In my case, I followed Charlie Parker and began using. Well, a lot of guys were using drugs really. Fats Navarro, the great trumpet player, died at a very early age from drugs, and a lot of the guys were on drugs really, a lot of the great bebop players. And I went along and I got messed up, and it took me quite a while to straighten myself out, you know.

How tough was it?

Sonny Rollins: It was pretty tough. It was very tough.

I went through some really terrible times. I don’t know whether I should really even mention it, but you mentioned that I had to go to prison and all that stuff. I was in a state where they had me in a straitjacket at one time. Can you understand what it would feel like to be in a straitjacket? I know. I couldn’t either, but I was, and it was brought about by sort of a drug psychosis in prison. I mean I just went completely… But it was tough, it was tough. I mean at that time they put you in — there’s a place in New York they used to call the Tombs. You’ve probably heard of it. I mean it was like a living tomb, with all the people. So I was there, and the withdrawal — physical symptoms, which were unbelievable.

But I had my family. I was a very bad guy. I used to steal from my house. I was just an outlaw, an outcast. My father was in the Navy, he wasn’t really around during this time.

I was a pretty bad guy. But my mother’s love and her belief in me, I think — and Charlie Parker, who took me aside and told me that this was not the way to be — that had a tremendous effect on me, so that I finally realized that, well, I am not going anyplace. I’m a pariah. People see me coming, they go across the street, you know. So I eventually was able to go to a hospital. There used to be a big hospital in New York — not in New York — in Kentucky, Lexington, which was a very good place. It was a place where you were able to treat addicts, something like the Betty Ford Clinic in later years. Anyway, you were treated in a humane manner, as a sick person, not as a criminal, and you went there for a certain amount of time, and you took what they called “the cure.” I went there voluntarily, and by that time I was determined to get away from drugs, so I was able to go there, and through my determination to do it, that place served me well.

If I didn’t have the determination to stop, it would not happen, because there are people that went there, that still used drugs when they came out. Several people over the years have come to me, asking me about Lexington. In fact, there was recently a guy who wants to write a book about Lexington, the rehabilitation center there.

During all this time, were you without your music?

Sonny Rollins: I wouldn’t say I was without my music. I always had my music. I would get involved with the bands in these institutions. My music was always with me.

You have described it, if you were quoted correctly, as walking into the lion’s den and coming out alive. Is that right?

Sonny Rollins: Yeah, I guess so, although I think I might have a better chance with a lion than with some of these substances. But yeah. That, in effect, is what happens.

A lot has been written about the so-called sabbaticals that you have taken, this willingness to turn your back on your career, and not perform in public for a period of time, like when you went to practice on the Williamsburg Bridge. How do you explain these breaks in your career?

Sonny Rollins: I have always been a person that has had a strong sense of right and wrong, a strong spiritual guide or guardian angel or belief maybe, I don’t know how to explain it, but a conscience maybe. There was always something inside of me that was talking to me all the time. When something talks to me, like the thing with the drugs, I realized something said, “Yeah,” and it finally came to me, “This is not the way to go.” I just have that in me, and when I find something that I want to do, I block out everything else, and I would do it. It’s the sense of right and wrong, so it doesn’t matter to me that people were saying, “How can you leave the music? Because they won’t accept you back if you go away. You will lose your edge,” and all. This was inconsequential to me, because I had an idea that I wanted to improve my self, my musical arsenal, if you will. So I do what I want to do, and that’s that. I am very strong about that, and this has held me in good stead, just listening to the inner voice. This is what I do, and I am happy about it, that I have that much determination, if you want to call it that. That’s what I have done all my life, and the sabbaticals were the same.

I went away from music for certain reasons. The bridge was the one you mentioned. That was sort of self-improvement.

I realized I wasn’t sounding as good as my reputation was, so I wanted to kind of get to that point where I wouldn’t be ashamed to go on the bandstand, which happened to me one time on a job I was playing with… Elvin Jones, at that time, was the drummer playing with me. We used to go around, had a big sign, “Sonny Rollins is coming to town,” everybody was there, but I didn’t sound good, and I knew I wasn’t playing up to what I should be. So I said, “Okay, I am getting out of here. I am going to go and woodshed,” as they say, and get myself together.

So I do things like that, if I feel that there is some reason to do it. Anyway, that was the bridge and other things.

How did you end up practicing on the Williamsburg Bridge in New York City? Could you even hear yourself while you were out there?

Sonny Rollins: Well you know, that was an accident. I lived down on the Lower East Side, and experienced some of the problems with trying to play a horn with neighbors, so I had to find someplace to practice. I practiced in the house because I had to practice, but I felt guilty sometimes, because I’m a sensitive person, and I know that people need privacy in the apartments. So anyway, I just happened to be walking on Delancey Street one day. That was the neighborhood I was in. I had moved down to the Lower East Side, and we had a small apartment there. It was a nice time. I had a lot of friends there. I was welcomed really in the neighborhood by the people on the Lower East Side at that time. Anyway…

I was walking along Delancey Street, and I just happened to look up and see these steps. I wasn’t thinking about anything, so I just walked up there, and I walked up the steps, and there, of course, was the bridge, and it was this nice, big expanse going over. There was nobody up there. So I walked, I started walking, I said, “Wow. This is what I have been looking for. This is a private place. I can blow my horn as loud as I want.” Because the boats are coming under, and the subway is coming across, and cars, and I said, “Wow, this is perfect,” and it was just serendipity. Then, I began getting my horn and going up there, and it was a perfect place to practice. Every now and then somebody would come across, but it was perfect. I would go up there at night, I would go up there in the day, I would go up there, I would be up there 15, 16 hours.