We're not talking about brain surgery here. This is finance — add, subtract, multiply, and divide.

Stephen Schwarzman was born in Philadelphia and grew up in nearby Abington, Pennsylvania, where he attended public schools. From an early age, he worked alongside his father in his grandfather’s drapery and linen business. In high school, he ran track and was elected president of his student body. He studied social sciences at Yale University: psychology, sociology and anthropology, but not economics. As graduation approached, he was still uncertain what he wanted to do for a career. During a homecoming weekend, he met Yale alumnus Bill Donaldson, and after graduating in 1969, he joined Donaldson’s investment banking firm, Donaldson, Lufkin & Jenrette. In his six months with the firm, he developed a taste for corporate finance but became keenly aware that he needed more training before he could make a career in the field. After fulfilling his military service obligation in the Army Reserve, he entered Harvard Business School, graduating in 1972.

Schwarzman interviewed with a number of investment banking firms before deciding corporate finance was his true interest. He joined Lehman Brothers, where he developed a formidable expertise in mergers and acquisitions and made a favorable impression on the firm’s new chairman, former Commerce Secretary Peter G. Peterson. By the time of Lehman Brothers’ 1977 merger with Kuhn Loeb, Schwarzman was a rising star in the firm, and at age 31, he became the managing director of Lehman Brothers, Kuhn Loeb, Inc. In his last two years with Lehman, Schwarzman chaired the firm’s Mergers and Acquisitions Committee. Peterson was pushed out of the chairmanship in 1984, and Schwarzman managed the acquisition of Lehman Brothers by American Express. Not long after the merger was completed in 1985, he left the company to embark on a new venture with his former boss and mentor, Pete Peterson.

Schwarzman and Peterson proposed to build an investment firm of their own, The Blackstone Group. With two employees and only $400,000 of their own money, they set out to compete with industry giants Salomon Brothers, Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley. In the mid-’80s, there was widespread interest in leveraged buyouts, the buying of companies with borrowed money. Schwarzman wanted to start big and raised nearly a billion dollars for Blackstone’s first private equity fund. Private equity funds invest in privately held companies, those whose shares are not traded on the public stock exchanges. In this opportune moment, Blackstone prospered, as Schwarzman applied his expertise in a merger-friendly environment.

In 1991, in the depths of a recession in the real estate market, Schwarzman took the plunge into real estate. Again, he had chosen the perfect moment, acquiring highly lucrative properties at depressed prices. In the following years, Schwarzman and Blackstone invested in a wide variety of industries, including health care, high tech, and communications. At first, most of the group’s investments were concentrated in the United States, Britain, and Germany.

In 2004, Schwarzman picked up the German chemical company Celanese, when most investors were avoiding the chemical industry. He took Celanese public in the U.S. at a time when interest in chemical stocks was rising and reaped a windfall. In addition to its private equity operations, Blackstone manages hedge funds and provides restructuring advice to corporate clients. In the 1990s, these consulting and advisory services took Blackstone’s activities farther east, to Japan and India. The firm has assisted in some of the largest mergers ever transacted between Japanese and American companies and, since the late ’90s, has been a principal adviser to Sony on its foreign acquisitions. Under Schwarzman’s leadership, Blackstone has also led the bankruptcy restructuring of troubled businesses such as Enron and Global Crossing. In 2007, in the biggest leveraged buyout in history, Blackstone acquired Equity Office Partners for $34 billion, taking possession of 540 office buildings around the United States. The deal was quickly followed by the acquisition of the Hilton Hotel chain.

At the height of its success, Schwarzman made the unprecedented decision to take Blackstone public, a first for a private equity firm in the United States. For the preceding five years, Blackstone’s real estate and private equity funds had earned more than 30 percent a year for their participants, primarily institutional investors such as public and corporate retirement funds. Taking the firm public enabled ordinary individual investors to participate in Blackstone’s unparalleled earnings. In the largest initial public offering (IPO) in history, Blackstone entered the market at a value of over $40 billion. This innovative move set off a wave of IPOs by other private equity firms. At the time, Blackstone controlled nearly 50 companies, businesses ranging from orthopedic devices, Gold Toe socks, and Michael’s art supplies stores to Vlasic Pickles and Aunt Jemima pancake mix. In 2008, Blackstone acquired GSO Capital Partners for an estimated $1 billion; GSO is now the credit investment arm of Blackstone.

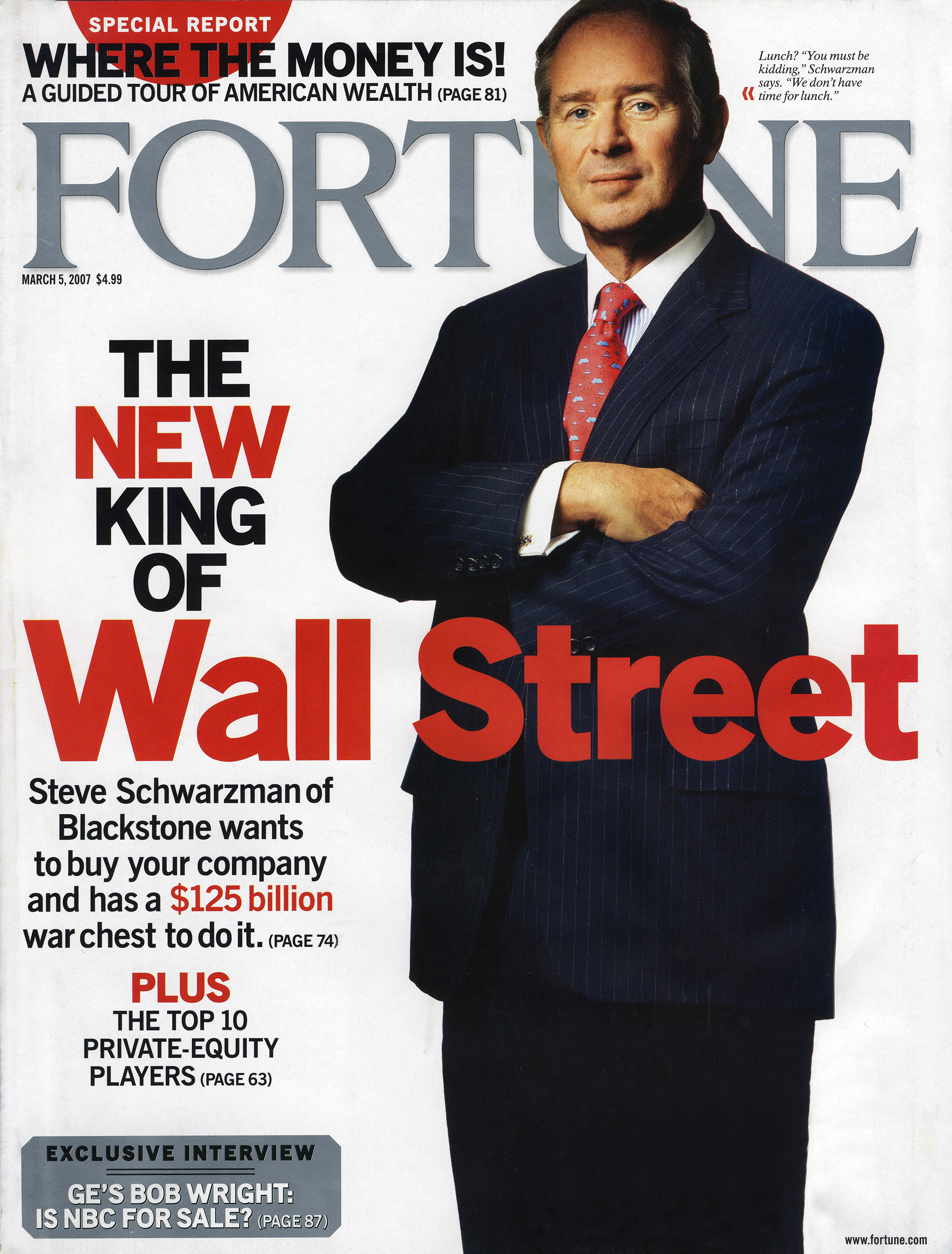

At the end of 2007, it was estimated that Blackstone had access to credit of $125 billion to acquire new companies. Stephen Schwarzman’s management of Blackstone’s investments had made him a billionaire several times over. His personal shares in The Blackstone Group were valued at $7.7 billion, and he was earning well over a million dollars a day.

The following year, the collapse of the U.S. housing market brought about an unprecedented contraction of credit and the downfall of many of the country’s largest investment banks, including Schwarzman’s old firm, Lehman Brothers. Although Blackstone had anticipated the subprime mortgage meltdown, it was not invulnerable. The firm continued to post a profit in the first half of the year, but in the third quarter of 2008, it reported losses of over $500 million. As the company marked down the value of its holdings, its own stock price fell to a fraction of its former value. In the midst of this turmoil, Blackstone’s financial advisory business continued to show a profit, as troubled corporations, including insurance giant AIG, turned to Blackstone for counsel.

Schwarzman and his wife, intellectual property attorney Christine Hearst Schwarzman, maintain their principal residence in New York City. An enthusiastic supporter of the arts and culture, Stephen Schwarzman is a longtime director of such major cultural institutions as the New York Public Library and the New York City Ballet. From 2004 to 2010, he also served as Chairman of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington, D.C. In 2008, he donated $100 million to the New York Public Library to finance the renovation of its main branch building on 42nd Street and Fifth Avenue. The 100-year-old Beaux Arts landmark has been renamed in his honor.

He has also been a generous benefactor of his alma mater, Yale University. In 2015, he made a gift to the university of $150 million to establish a new center for cultural programming and student life. This was the second-largest gift made to Yale in its 300-plus-year history. An even more ambitious project is the creation of Schwarzman College at Tsinghua University in Beijing, China. Every year, approximately 200 university graduates from the United States, China, and other countries are to be given the opportunity to earn graduate degrees in public policy, economics and business, or international studies. The one-year program, conducted in English, is intended to prepare a new generation of leaders for a world in which China is destined to play an increasingly large role. As the Rhodes Scholars of the 20th century played a major role in aligning the interests of the English-speaking nations, it is Stephen Schwarzman’s hope that the Schwarzman Scholars of the 21st century will build a network of relationships that foster peaceful cooperation among China, the United States and all the nations of the world.

Shortly after the 2016 election, President-elect Donald Trump named Stephen Schwarzman to chair a new business advisory council, the President’s Strategic and Policy Forum. The forum met from February 2017 through the following August.

By 2022, Stephen Schwarzman had amassed a personal fortune of more than $36 billion. His income of $734.2 million from Blackstone in one year alone made him far and away the most successful executive in the private equity sector. Blackstone Group LP is the world’s largest alternative investment firm, managing $881 billion in private equity, real estate, and other assets.

In the autumn of 2018, the Blackstone Group acquired Clarus, a leading global life sciences investment firm. With offices in Boston and San Francisco, Clarus has focused on funding growth-stage investments, often through research collaborations with major biopharmaceutical companies. It is the first acquisition of Blackstone Life Sciences, a new private investment platform that focuses on funding research by major pharmaceutical companies and investing in new companies to help them grow past the venture capital stage of fundraising. Blackstone Life Sciences aims to accelerate the development process for new drugs and health technology, shortening the timeline from creation to market.

At the same time, Stephen Schwarzman made a personal gift of $350 million to Massachusetts Institute of Technology, leading the $1 billion effort to create the Stephen A. Schwarzman College of Computing. The college will create 50 new faculty positions and a host of graduate fellowships to educate “the bilinguals of the future,” scholars who will apply expertise in computer science and artificial intelligence to the disciplines of biology, chemistry, politics, history, and linguistics.

Schwarzman’s goals for the college include keeping the United States competitive in the global marketplace while preparing students to deploy artificial intelligence in ethically responsible ways. It is anticipated that Schwarzman College graduates will participate in the political process and in crafting public policy. Stephen Schwarzman relates his passion for AI to his own experience practicing pattern recognition in markets and financial data. “The idea of building data sets and employing them,” he has said, “is one of our firm’s enduring competitive advantages, from day one of our strategic plan.”

Stephen Schwarzman’s philanthropy continues to reach beyond the borders of his own country. In 2019, he donated $188.75 million to the University of Oxford, the largest gift in the 800-year history of Britain’s oldest university. The Schwarzman Centre, will house Oxford’s new Institute for Ethics in AI. Schwarzman’s gift is intended to facilitate the integration of the humanities, particularly philosophy, with the exploding field of artificial intelligence.

In March 2023, Stephen Schwarzman was featured on Forbes‘ “World’s Billionaires” list with an estimated net worth of $27.8 billion.

In July 2023, Blackstone made financial history by becoming the first company in its sector to reach a staggering $1 trillion in assets under management. Achieving this milestone ahead of their 2026 target set in 2018, the firm credits their success to a strategic shift towards lower-risk, lower-return strategies such as insurance, infrastructure, credit, and certain real estate ventures. The firm’s assets rose from $991.3 billion to $1 trillion in Q2 2023, with inflows of $30.1 billion pushing them past the threshold. This significant achievement was not without its challenges; while net income rose to $601.3 million, distributable earnings fell due to a less favorable environment for asset sales and IPOs. Despite its success, Blackstone remains focused on growth, living up to Schwarzman’s mantra to “go big” and commit to ventures with “almost limitless possibilities.”

In 2015, Steve Schwarzman’s encounter with Jack Ma catalyzed his interest in AI, leading to over $500 million in donations towards AI education and research. Significant contributions include establishing the Schwarzman College of Computing at MIT, officially opening at the end of April 2024, and the Schwarzman Centre for the Humanities at Oxford University, focusing on AI’s ethical implications. Beyond philanthropy, Schwarzman has advocated for AI in policy and integrated it within Blackstone’s operations. His efforts highlight a transition from traditional finance to championing AI, aiming to ensure the U.S. remains at the forefront of technological innovation and ethical considerations in AI.

In October 2025, Stephen Schwarzman emerged as a key intermediary in negotiations between Harvard University and the Trump administration over billions in federal research funding. At Harvard’s request—and with the president’s encouragement—he served as the lead voice for the university in calls with senior administration officials, seeking to broker a pause in the White House’s pressure campaign in exchange for certain policy concessions. His involvement helped reopen stalled talks, though no final agreement was reached. The administration pressed for greater control over Harvard’s admissions, employment, and curriculum—measures the university argued would violate its legal rights. Leveraging his longstanding relationship with Donald Trump, Schwarzman was among the few private-sector figures able to communicate directly with the president, continuing his role in major policy debates and underscoring his political relevance without holding public office. As of October 2025, at age 78, Schwarzman was worth more than $50 billion, ranking No. 32 on Forbes‘ list of the world’s richest people.

At age 31, Stephen Schwarzman was managing director of Lehman Brothers, one of Wall Street’s leading investment banking firms, but after merging Lehman with American Express, he chose to strike out on his own. With one partner, two employees and less than half a million in start-up cash, he set out to compete with Wall Street’s reigning giants.

From these unpromising beginnings, Schwarzman built America’s leading private equity firm, The Blackstone Group, and made brilliant strategic investments in almost every sector of the economy. After completing the largest leveraged buyout in history to acquire some of America’s most profitable real estate, he took his firm public in the biggest initial public offering recorded to date, giving ordinary investors a chance to participate in Blackstone’s unprecedented success.

Schwarzman’s investments made him a very rich man, but they also made the American economy more efficient and productive, rescuing troubled companies from insolvency and building small companies into big ones. Although Blackstone and its holdings declined along with the rest of the economy in the global credit crisis of 2008, the firm and its chairman remain major figures in the world financial scene. In addition to his achievements in finance, Stephen Schwarzman is one of his country’s leading patrons of the arts and culture; in recognition of his generosity, the main branch of the New York City Public Library now bears his name.

(The Academy of Achievement interviewed Stephen Schwarzman in Washington, D.C. on June 20, 1999, and again, in New York City, on February 20, 2018. Transcripts of both interviews are combined here.)

You’ve said that when you were a student, you imagined yourself as being like a telephone switchboard. What did you mean by that?

Stephen Schwarzman: They’re now obsolete, but in the olden days, what a telephone switchboard would do is take in incoming calls, sort of whip them around, and then connect you with some other place that you were trying to reach. And that’s sort of the way I saw myself. You know, I’m not much of a self-starter — in other words, sitting in a room thinking great thoughts. But if I can see things that are happening, if I can feel what’s going on, then I can do something with them, and I make them go some other place, create something, do something with it. So I need those inputs. I’ve got the processor, and then something magic happens coming out. So that’s what I thought was my basic purpose or skill or whatever.

What are the inputs that you take in now for your very special processor?

Stephen Schwarzman: Now it’s amazing because there are so many inputs through my work life. I get to hear about what’s going on in every part of the world, with every asset class, with different kinds of companies, real estate. I can get a unique overview every week of what’s happening, and that’s also got a political overlay to it. So then, of course, we are now in an Internet world where there are all these other inputs, and television is no longer three network channels. It became four, and now there are hundreds of inputs and more publications.

How do you pick what to pay attention to? How do you sort through all that data?

Stephen Schwarzman: We set up a system that’s terrific here, where, every Monday, each one of our big areas — private equity, where we probably employ about 500,000 people, one of the biggest in the United States; real estate, where we’re the largest owner of real estate in the world and, you know, sort of our capital extension in the debt business — each one of these areas reports and tells you everything that’s going on. I don’t have to pick. It picks itself. And the people in that group describe what’s going on in the world. I’ve only been doing this for over 30 years. So you get these feeds from — it’s raw data, and this is before there was a fixation on data. We get it all the time. What works for me is the way my mind, I realize now, works is I look for changes — not what’s going on; anybody can see what’s going on — that what I’m most interested in are those little imperfections. I call it a piece of white lint on a black dress. Usually people just brush it off. I keep looking at it. What’s it doing there? Why has that happened? What does that mean? Because what I’m looking for — I guess you’d call it some kind of an odd pattern recognition — is something that’s changed from the normal order.

Can you give us an example?

Stephen Schwarzman: We were looking at buying some real estate. This is a business example, but there are examples from other areas. We were looking at buying some condominiums in southern Spain in the 2006-2007 era, and we did some analysis and had a meeting. And the team reported that they were building so many units in Spain that you could move most of Germany into Spain and there’d still be extra units. And then somebody commented from our Indian office, which I didn’t even realize we had, that the same thing was happening in India and that raw land had gone up ten times in 18 months, which seemed like an impossible thing. Then that weekend, I was in Florida, in my house there and reading the newspaper, and it said that real estate prices for houses were up 25 percent in one year, with like a one percent growth in population. So you could see a global residential housing boom so strong that it was meant to collapse, which, of course, it did. So we adjusted everything we were doing at the firm to not get caught in that mess. I can go over in more depth exactly what we did. It’s actually not that important except we changed our entire array of where we’d invest, where we wouldn’t invest, and when the subprime crisis happened, where the global financial crisis was triggered, we were positioned in a much different way than almost everybody. And you could see it just with one or two pieces of information. So that’s the way my mind sort of works.

What do you think is different about you or how your mind works?

Stephen Schwarzman: I just see connections of things that I think are sensible. One of the differences — when I see something like that and I figure it out, I’ll do it. Part of what I’ve discovered in life is most people don’t like changing what they do. They’re quite happy the way they are. Even if they grumble, that isn’t enough to make them change course. So when I see things that are different than other people see them, they’re always fact-based. They’re not my opinions. I can explain what will happen, and why, and hardly anybody cares. In fact, they say, typically, “That’s interesting,” and then they go back to what they’re doing. I don’t understand why it doesn’t change their behavior. But it certainly changes mine. Because I’m now in a position at my own business, Blackstone, and in other things that I do, where, when I see something that I think is worthy of a real course correction — which involves starting new things, doing new things — I go and do it. I don’t hesitate.

Where does that confidence come from, that you don’t have that fear of risk or failure?

Stephen Schwarzman: It’s not risk. I hate risk. I don’t take risks. Risk is when you’re uncertain about an outcome but you go there anyhow.

But how can you be so certain when you’re doing things that no one else has done before?

Stephen Schwarzman: Because they’re all logical, and I can explain why they would work. I don’t find anyone who says, “I don’t think it will work.” They just don’t want to do it. The way I think is, whenever I see one of those opportunities, that’s the least risky thing in the world. First, you have no competition. That’s one of the things that makes it very easy to go there. And you know why you’re going. It’s no different than playing basketball, and everybody’s guarding everybody, and all of a sudden somebody guarding you falls down, and you’re ten feet away from the basket. It’s a completely open shot. You take it. You don’t think about it.

You’ve put together deals in ways that nobody else has done before. Can you take us through a specific instance, from the germ of an idea to the actual execution?

Stephen Schwarzman: We bought a company in 2007 with a funny name. It was just acronyms, EOP. It was the largest office company — office buildings — in the world. Nothing close. It was worth about $40 billion. And it was near the top of the real estate cycle. We thought it would be interesting to buy for a number of reasons. But the price of the deal started getting higher. It became competitive. So we did some interesting tactical things to make sure we won. But I was so scared that we were winning — because we could have taken $500 million, I believe, to just go away and let somebody else win. That just made me — I couldn’t sleep at night because it was right on the margin. So we decided to sell half of what we bought because, if you have a huge group of buildings, you can sell them as one or two buildings. You can sell them by city. You can sell them by area. So what we did is we bought at one price — which was around 5.7 percent yield — and we sold them. We thought we could sell them at four-and-a-half. Roughly what that does is it increases the yield on the stuff you have left, so it’s safer. So we decided to do that. And I said, “I don’t want to take one minute of risk. This deal is so risky. So I want to simultaneously sell half the day we buy,” and the seller of the whole company didn’t want to do that. And I said, you know — we said we’d walk. We wouldn’t increase our bid to be the buyer. And they said okay. So imagine buying $40 billion of real estate one day and selling $20 billion of it the same day. The most amount of real estate that was ever sold in history in a year was $10 billion. So we were doing six times what anybody did in one day. And I did that because I was scared because I hate risk.

What does it feel like when you’re making a deal and you know you might lose billions of dollars?

Stephen Schwarzman: I don’t want to lose one dollar! You know, part of what makes people is their background. I came from a background where to get spending money or do anything, I had to have jobs. I cut lawns. I shoveled snow. And then I recruited my brothers to do it, and I kept half of the profits. That lasted a few years before they realized they could do it all. I always did things. I sold lightbulbs door-to-door. I sold stationery door-to-door in college so I could get a KLA stereo. I did all kinds of things. When you do stuff like that, you really never want to lose your money because then you just have to keep doing more. That’s a huge effort to knock on somebody’s door you don’t know. You don’t know what’s going to happen. You only do it because you really want to be successful. So I’m not a believer in going backwards. It’s not something I endorse. I only like to go forwards. So I worry about making a mistake, any type of mistake. Part of the culture at our firm — it’s a little different than most — the first rule is don’t lose money. I know this sounds primitive. You don’t have to go to Harvard Business School for this. But if you have a philosophy of trying never to lose rather than how much you make, you always end up making a bunch on interesting things. But if you don’t have a downside, and you only have an upside, and you’re in a growing economy — which is where we operate — and you do it on leverage, you’ll make very, very high returns, and we have — so it’s a pretty simple model.

You’re well known for making huge amounts of money in these big deals that you’ve done. What’s the most you’ve ever lost in a day?

Stephen Schwarzman: In a day? You don’t lose it in a day. You lose it over a project. We had one where we lost a billion dollars. We’d bought a significant percentage of a telephone company in a European country, and we were partners with the government, who had the largest share. We had the second. We had a whole transformation project to have that company do much better. It used to be owned by the government. We agreed on it completely, and we would have made a very good return. Then there was an election, and the government basically said, “I’m sorry. I know I told you I wanted to do all these things with you, but I’m not doing it.” And this is a big country with famous people. You go over, and you sat down with them, and you said, “But you told me!” And they said, “Well, things changed.” So we lost almost all of our money on that.

You’re at the pinnacle of success now, not just in business, but you have heads of state reaching out to you for advice. Is success all that you thought it would be?

Stephen Schwarzman: Yeah. In fact, it’s more because it’s optionality, and it’s fun. It’s not about financial return. It’s about the ability to create and do and help people and connect the dots, whether it’s in the business world, whether it’s in the philanthropic world, whether it’s in the political world. You just have enormous access and the ability to address issues in a really positive way. So, gee, my life’s never been more exciting. It’s wonderful.