I do not know the word ‘quit.’ Either I never did, or I have somehow abolished it.

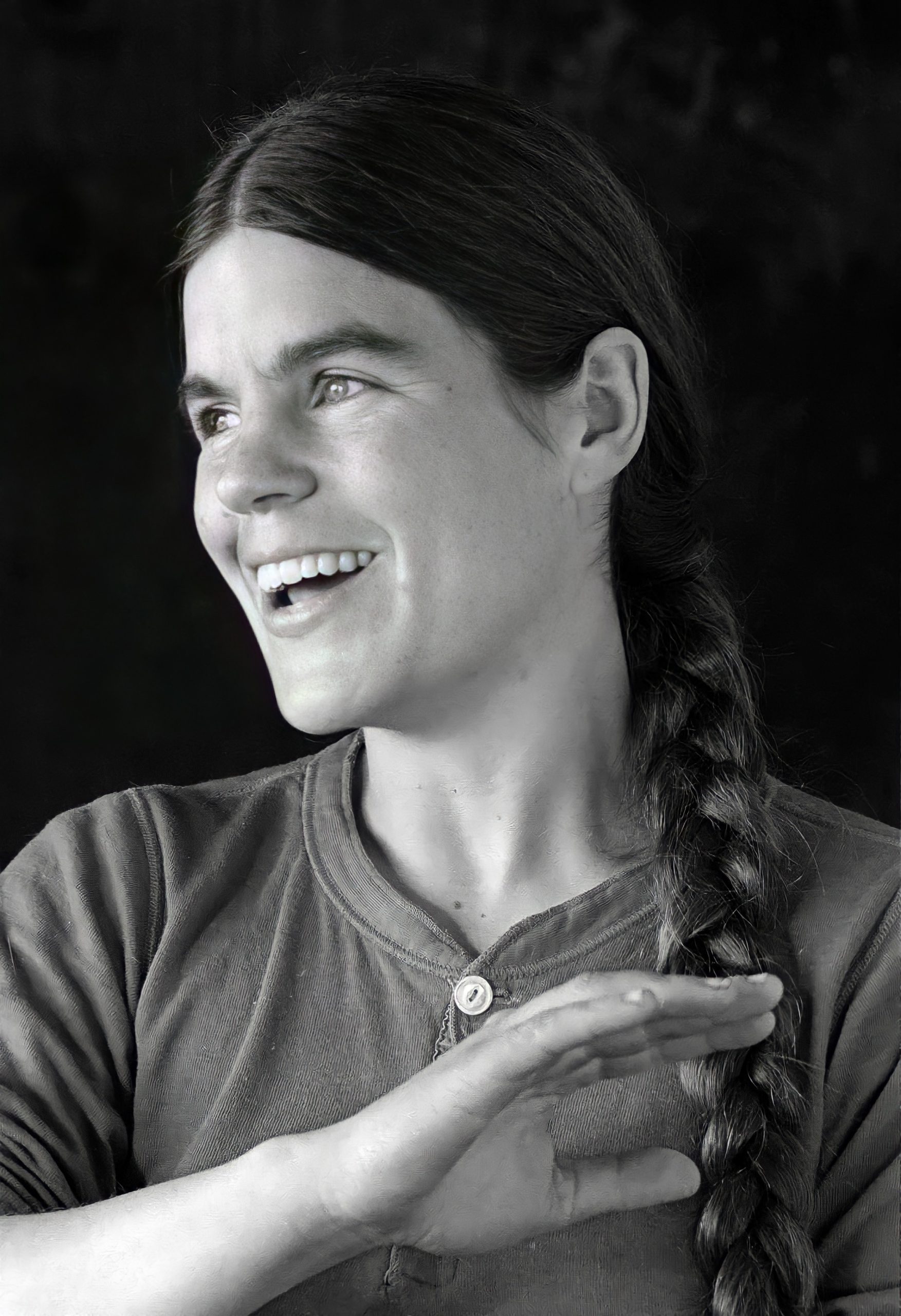

Susan Howlet Butcher was born in Boston, Massachusetts. Her love of the wilderness and animals drew her to Alaska when she was 20 years old. Starting out with only two dogs, doing odd jobs during the summer months in order to live through the long winters, she eventually rose to become the most famous dog musher in the world.

A disciplined and fearless adventurer, she was the first person to win three consecutive Iditarod championships, from 1986 to 1988. The Iditirod is a 1,152-mile race across the spectacular but brutal Alaskan wilderness. Competitors endure 100 mph skin-ripping winds, blinding snow, and temperatures reaching 70 degrees below zero. Butcher, who raced in her first Iditarod in 1978, finished in the top five from 1980 to 1984. In 1985, she was leading in the early stages of the race when a sick and dying moose blundered into her path on the trail. A few frantic minutes later, two of Butcher’s dogs were dead, others were injured and she was out of the race.

The following year, she returned to win the race, triumphing again in 1987 and 1988. In 1989, she finished second but returned to win once again in 1990 — four first-place finishes in only five years, an Iditarod record. In all, she would finish in the top five in twelve Iditarods. No musher has ever so dominated the sport.

“You have to be very selfless in your dedication to your dogs. When you come into a checkpoint, although there may be a wood stove to warm your feet by, you stay outside; you take care of your dogs, get them bedded down and fed. It may take three hours. Then you can go and have your 15 minutes inside, and then it’s time to go and check your dogs, massage them down and get ready to go again. I might get a catnap,” Butcher told The Los Angeles Times.

At the peak of her racing career, Susan Butcher stood an athletic five feet six inches and weighed 135 pounds. Her success was the result of long training. “At a pace of eight or nine miles per hour” she said, “you do some riding that can be fairly relaxing, but the majority of it you’re either pumping with one leg or running. The most strenuous is going over the rough terrain and having to steer the sled, which weighs 150 to 200 pounds with all the gear in it. Throwing the sled around is as exhausting as pumping or running.”

Two of her favorite lead dogs were Granite and Tolstoy, each of whom led her to victory. Like all Alaskan Huskies, Butcher said, “They live to race. They like the competition. They understand the competition. They want to pass the teams ahead of them. You need only one to three dogs to pull you and the sled and the gear, so it’s way overkill, and you have this immense amount of power. You’ve got nothing but a voice command. There are no reins or anything. It’s all ‘gee’ for right, ‘haw’ for left, ‘whoa’ for stop.”

Butcher lived with her husband, fellow dog sled racer David Monson, in the remote area of Eureka, where they raised two daughters and a pack of wonderful sled dogs. For many years after her retirement from competition, Susan Butcher owned and operated Trail Breaker Kennel, first in Eureka, and later in Fairbanks.

In 2006, she died of leukemia at the age of 51. In the years following her death, the State of Alaska honored her in a number of ways.

In 2008, the state legislature established Susan Butcher Day, to be observed on the first Saturday of March each year. Later that year, the University of Alaska at Fairbanks announced the creation of the Susan Butcher Institute, to develop public service and leadership skills among young Alaskans.

“I have been known to walk in front of my team for 55 miles, with snow shoes, to lead them through snow storms, in non-racing situations, where I could have just as easily radioed for a plane to come and get me.”

Susan Howlet Butcher was an animal lover, a business woman, a wife and a mother. She was also called “the best competitive dog sled racer in the universe.” Before her, there were many women who competed in sports, but not many who entered the race called the Iditarod, one that took her 1,152 miles across the Alaskan wilderness, enduring 100 m.p.h. winds, Arctic blizzards, snow blindness, wild animals, thin ice, sleep deprivation, avalanches, and every other hardship nature can inflict in the land of the midnight sun.

Butcher won this race four times in five years, so often that “Iditarod,” as well as the sport of mushing, became synonymous with her name.

It would be hard to say whether Alaska found Butcher or Butcher found Alaska. Drawn to the great northern wilderness from her love of animals and disdain for cities when she was 20 years old, she became an outspoken advocate for wildlife and the environment, and educated the public about the proper care of animals.

Combining an arduous training schedule for herself and her dogs with an ability to focus on a goal with extraordinary discipline and singleminded force, Susan Butcher was a true champion — one of those few who exemplify a given sport in the minds of millions.

What is it like to compete in the Iditarod? It’s 1,000-plus miles over rough terrain, from Anchorage to Nome. Can you try to describe it for us?

For the musher, the most difficult aspect is the lack of sleep. And it is an ongoing and constant thing that you are aware of. We are getting between one and two hours of sleep a day for perhaps an 11- to 13-, 14-day race. It turns out a little bit more than that.

In a 12-day race I’ll get about 20 hours of sleep. Most people think that fact in itself would make this an extremely grueling, totally uncomfortable race. Then you add to it the cold. We are often as cold as 50 below. You have the windstorms; you have the snowstorms; you also might have forty above zero. You have a lot of elements that are causing what most people view as discomfort. But again, the thing to remember is that we live in that all year round. And, although, yes, I am very, very cold at fifty below, and even as good as I have learned to dress in those temperatures, I am not going to say I am completely comfortable. Yet, I know how to deal with them, and I am not miserable. Although sometimes you are! But I am often not miserable. So the thing that I think is important for me to say is that the country we are going through is so magnificent and beautiful. Even though I’ve gone through this same country many, many, many times, it is never anything less than spectacular. And it is always changing. Every 20, 30, or 40 miles, you come into a totally new terrain. Maybe you are in some really tall mountains, the Alaska range, or one of the other ranges we go over. You could be on the Yukon River, which is, at some points, a mile across. Just magnificent. Or the frozen tundra, which is not beautiful in the same sense as the mountains, but awesome in it’s expanse. So there is always something beautiful to look at. If it’s the night, you may not be able to see anything except for the stars, and more often, the Northern Lights. So we are always out in the spectacular nature and the wilderness, and no matter how tired you are, no matter how cold you are, you are able to appreciate that.

Most important is that you are out there with your 12, 16, 20 best friends — the dogs. I have raised each one of them. I have trained them. I know each little personality. I know what they are thinking as they are going down the trail, each individually. They are all thinking different thoughts. I know how much they’re enjoying it. And I can see the work that we have accumulatively put together — to make this team perform the way it is obviously performing for me, if I am being able to win, is so satisfying and fantastic. To me, today, there is nothing that brings me more joy than to see a 16-dog team trotting down the trail with just as much power as you could muster. It’s just a beautiful scene to me.

You’ve said you enjoy the scenery while you’re running the race, but you also must have things to worry about out there.

Many people say, “What do you think about for 12 days?” Well, you are constantly, at every step of the way, worrying about steering the sled, making sure that the dogs are going the direction that you want them to, staying on the trail, so on and so forth. The trails are not huge, beautiful paths. We go over boulders, over fallen trees, over bare ground, twists and turns and down through mountain gorges, and over glare ice, through open water, everything. The actual steering of the sled for the musher is very physically demanding. In addition, you are trying to watch what’s going on two or three feet in front of the sled, you’re looking at your lead dogs way up there, and at every dog in the team, making sure that they are okay, taking the bends correctly, and that there are no problems. That is really what you are spending your time thinking about when you are mushing down the trail.

You are constantly checking how each individual dog is performing — is one tiring before the rest of the group? If so, it’s time to stop. You always stop for the weakest dog, not the strongest dog. When should I stop next? What should I feed them next? Where, when is the next checkpoint? You’re trying to look at the terrain around you, trying to figure out where you are. I have a map, a compass. I’m constantly checking my watch, trying to find out if I am lost or if I am on the right trail. All of these things are of great concern every moment of every day.

In addition, you are in a race. You are not just on a survival trip. So you are worrying about where so-and-so is. Perhaps you just passed a fellow musher stopped by the trail. Is he going to stop for a half hour, is he going to stop for four hours? What does this mean to my strategy? When did I last see him? Let’s see, he left the checkpoint a little bit in front of me. Am I moving faster than him? All these types of things. Or perhaps you literally pass somebody on the go. Well, that’s a wonderful feeling, and you say, “Aha! I’m faster!” or, “At this point in the race I am faster.” So it’s a great game of strategies. It’s a great game of dog care. Do you want to be out in the lead? How much faster are you than another one? When should you take your rest periods, and when should you push? This is great.

Then you have the storms, and you have everything else that comes in to create havoc with what would be a perfect strategy. So it’s a balance between a survival act and a typical race. There are so many aspects; I think this is why it has held my interest for so long. There are always new things to get better at. Right now I am spending a lot of my time working on canine nutrition, on canine sports medicine. I am actually getting back into the veterinary field because I love it so much, to find out where I can enhance the team. But again, what I am looking for is not written in any book. I am working with veterinarians on the next step that they don’t even know about. And it’s really exciting.

It sounds like it could be dangerous out there.

There are a lot of dangers. We have avalanches. We have the dangers of the Arctic blizzards which are, in many ways, the most fearsome. Many people freeze to death every year who travel in those countries. No one has ever frozen to death in the race, but this happens typically with the local people, so we know that it is extremely dangerous. The open water is perhaps the thing we fear the most, or the thin ice. In 1984 I can tell a story of being ten miles away from a checkpoint village, an Eskimo village of Shaktoolik. I was traveling on some salt water ice, and I was quite a ways off land. And all of a sudden I realized that the ice was billowing around me. And so, just as I realized how dangerous it was, I gave the dogs the command to turn towards land, just as my sled broke through. So I went under, broke through, the successive dogs right in front of the sled broke through because of the weight of my sled. But the lead dogs and a couple pairs behind them were able to stay up on the hard ice and slowly but surely pull the rest of us out. It was probably about 30 below, and there is not one blade of grass out there. There is nothing to start a fire with to warm us up or dry us off.

So I just kept everybody moving. I ran for the next ten miles to keep myself from freezing to get to the next checkpoint. Now, this water that I broke through was deep enough to drown me, but just as often the danger is merely getting wet in temperatures below zero, where there is no shelter from the wind, and there is often nothing to start a fire with. That is a great danger. A less common danger, but nonetheless very serious, is the moose. The wolves are simply curious. They never cause us any problems. The bears, except for the polar bears, are in hibernation, and most of the polar bears are much further north than where we race. So the only danger for us really is the moose and the buffalo. But we only run through one herd of buffalo on the way to Nome. The moose generally run away from a dog team but occasionally they will somehow feel entrapped, and they feel they have to run towards you, and in essence, through the dog team. That has probably happened to me three or four times. No serious injuries to the dogs, none to me. Only minor injuries.

I was traveling alone at night in the lead of the race and ran into an obviously crazed moose. She was starving to death. There was something wrong with her. She was just skin and bones. And rather than run away, she turned to charge the team. I thought she would just run through me. I stopped the team, threw the sled over. She had plenty of room to pass us along the trail. She came into the team and stopped. She just started stomping and kicking the dogs. She charged at me. For 20 minutes, I held her off with my ax and with my parka, waving it in her face. And finally, another musher came along and we shot her, but not before she had killed two of my dogs, and she injured 13 others, leaving me to scratch from the race. She bruised my shoulder. We spent the next two weeks at a veterinary hospital, saving the lives of the injured dogs. So these things are possible, but this is very atypical. Mostly, the moose will cause little trouble. But these are some of the dangers that we have to be prepared for.

Your encounter with the crazed moose that killed some of your dogs, is that the worst thing that has ever happened to you in the Iditarod?

That is definitely the worst thing, as far as that it ended with tragedy. However, my close calls, my encounters with open water, have been much more severe and have been much closer to death for me and/or the team than this was. For the full team, this one ended very tragically. But I’ve got to say, I’m a lot more scared of open water than I am of moose today.

You’ve told a story on occasion about a time when a dog disobeyed your order and it saved your life. Is that true?

The most important thing that I believe my job is, is to train my dogs to have a “trust-and-be-trusted” relationship. This starts with me working with the puppies, training them to always trust that I will never ask them to go any further or faster than they are capable of; and yet, everyday, in some way, I will challenge them perhaps to go a little bit farther than they know they are capable of doing. However, if they show me they are not capable of something, I’m there to comfort and praise them, to give them whatever they need. If they do accomplish it, I’m there to praise them. I do this sometimes by just letting the puppies run loose, and sometimes the dog team. That trust is fairly easy to give to them. The other side of it is that I need to trust in them, trust that they are smarter in the wilderness than I am. I will many times have to depend on their lives, and my life, in their knowledge. And one of the first ways I found this out was after just two years of living in Alaska. I was traveling on a trail I had been using all winter long, which crossed a frozen river, and my lead dog, Teckla at the time, took off to the right. I told her to go back onto the trail. She took off to the right again. This dog never disobeyed me, and I could not understand why she was trying to do it. So I finally gave her her head, she pulled the team off to the side just as the trail collapsed into the river, and we all would have drowned. So she had a sixth sense that saved our lives.

It’s mutual trust. Theirs in my guidance, and mine in their ability and instincts, in the wilderness, that has saved our lives many times.

Has the thought ever crossed your mind, out there, during the toughest part of any of these races, that you just want to give up, just quit?

No. Absolutely not.

I do not know the word “quit.” Either I never did, or I have somehow abolished it from my language. If you allowed it to enter your mind, I think during the worst times when you are so exhausted, and so cold, and the dogs may be getting tired towards the end of a four- or five-hour run, you’d quit. You would. You have to see only that you are going into this specific race, whether it be a 300- or a 500- or 1,000-mile race, or individual training run. You are going to complete this. Then, if some force, such as the moose, becomes so great, it’s going to be obvious that you should quit. So you can’t think about “quit.” I just don’t think it even enters my mind. I am always so keyed up for the challenge, and not only in a racing situation where it would be quite obvious, because for the Iditarod I have trained for — let alone many years — an entire year for this race. Just because I got a little cold and tired would be a stupid reason to give up an entire year’s work. But even more so, I think the examples that show my lack of willingness to quit would be certain training runs. Runs where I may be out on a 500-mile trip, there is no reason why I have to make it from point A to point B. There is nothing driving me but my own desire to get there. And where I am getting isn’t even an important thing to me. It somehow is just to have that challenge. I have been known to walk in front of my team for 55 miles with snowshoes to lead them through snowstorms in non-racing situations, where I could have just as easily radioed for a plane to come and get me. Instead, I will take the other way out. And it’s certainly given my life incredible fulfillment.

What’s the strangest thing that’s ever happened to you out there?

Because of the lack of sleep, we do get to the point of hallucinations. I have learned now to take little 15-minute catnaps and how to stay mostly in control of these hallucinations. But my first years of racing, I was horrible. I had no idea how to sleep. I would usually go for two or three days without a single nap, and then I’d sleep for five hours. So I was not doing it right. And at one point in the race, I was traveling along, and I thought there were four of us on the sled and we each had a job. My job was to lean to the right if the sled would tip to the left. Another person’s job was to lean to the left if the sled would tip to the right. One person was supposed to use the brake, and I never did figure out what the fourth person was doing on the sled. But here we were going between Slatta Crossing and Ruby, over these huge hills, and I was doing a really good job in my job. Every time the sled would lean to the left, I’d lean to the right. But the others, they weren’t doing a good job at all, and we would tip over! And I would get my face completely full of snow, and you would think that this would wake me up out of this. I would throw the sled back up and yell at these non-existent people and off we’d go. I later found out by looking at my watch that this went on for almost seven hours. The way it stopped was I was going along and I fell off the sled, in my hallucination, and the team was running away from me. There’s a rope that drags behind the sled we call the snub line. Well, I grabbed the snub line, and I am yanking it, and yelling, “Whoa, whoa, whoa, whoa, whoa!” and they were disappearing off into the distance. I finally woke up because I did not have a hold of the snub line. Indeed I had lost the sled, and we have a headlight that we use on our head, and it has a cord on it, and I had a hold of the cord, and I was yanking my head up and down yelling “Whoa!” and I woke up to see my team disappearing into the wilderness. And I said, “This is bad. This is not good.” Luckily, they were as tired as I was. I told them to “Whoa!” and they stopped. I went up there, we camped, and I slept. But definitely, the hallucinations are pretty hysterical.

In one race, Joe Garnie and I were neck-and-neck — we often are — and traveling along in the northern arctic, up by Nome. The arctic tree line well below us. There are absolutely no trees up there. Well, I was in the lead and we got off the trail. I went up to the front of my team, and we were in a thick forest, and I had to lead my dogs through this forest. Joe came up behind me and said, “What are you doing?” and I said, “Well, I’m leading the team through these trees back to the trail.” He said, “Susan, there are no trees here.” And I said, “I know, but I can’t make them go away.” And he said, “Neither can I.” We both were seeing the same trees. We could not make our minds get rid of them and make a straight line to the trail. We wove our way through these trees back to the trail. So it’s quite amazing what exhaustion can do.

You had run the Iditarod seven times before you finally won. Can you tell us how you felt the first time you crossed the finish line in first place?

You know, when I first won the race, I think I was almost in shock. I don’t think I could enjoy what had happened until almost 24 hours later. I had worked so hard for it. And, of course, at this point in the race you are also so exhausted. There was certainly just a glow and a contentment in me. But to actually finally sit back and say, “I am the champion of the Iditarod!” This was something that had just been so high and just close enough to almost touch, but never touch, and all of a sudden I was there. It was amazing to me that I had actually reached a goal. And then, I think as anybody who reaches a goal knows, there is a depression that goes with that. I had experienced this with every finish of every Iditarod because that in itself is a goal — just to be able to finish. So I knew a little bit about it. But there was definitely a depression that happened after that. I worked quickly to combat it. Probably a week or two after the finish, I just said, “Well, it’s time to get ready for next year’s race, and I am going to win that one,” and I learned that was the way to battle that problem. In fact, the next year, what I did, after winning again was, as I was standing at the finish line and the media wanted to interview me about that race — the ’87 race — and ask me how it went, I said, “I don’t want to talk about this year’s race. It’s over. I’ve won it. Let’s talk about next year’s race. I’m coming back to win it again.” The instant I was done with that goal, I went on to my next. And I never went through the depression.