My writing all comes from listening. The more I can listen, the more I can write.

Suzan-Lori Parks was born in Fort Knox, Kentucky. Her father was a career officer in the United States Army, so the family moved frequently while Suzan-Lori was growing up. She went to school in six states, seldom spending more than a year in the same school. While her father served overseas in Vietnam, the rest of the family lived in Odessa, Texas, near Suzan-Lori’s maternal grandmother. The rhythms and similes of West Texas dialect made a lasting impression on Suzan-Lori Parks, whose work as a writer overflows with colorful dialogue, exploiting the rich resources of African American vernacular speech. A lively, imaginative child, Parks was an avid reader of mythology and folklore, and amused herself writing songs and stories. In 1974, her father was posted to Germany and the whole family moved with him. Suzan-Lori and her brother and sister attended local schools, where they soon became fluent in German. Both of Suzan-Lori’s parents emphasized the importance of education. After retiring from the Army, Mr. Parks became a professor of education at the University of Vermont. Her mother later became an administrator at Syracuse University. In high school, Suzan-Lori Parks dreamed of becoming a writer, but was discouraged by an English teacher who found fault with her spelling. Temporarily abandoning her dream, Parks entered Mt. Holyoke College in Massachusetts as a science student, but soon rediscovered her love of poetry and fiction, and decided to major in English and German literature.

By her own account, the highlight of her college career was a fiction workshop taught by the esteemed novelist and civil rights activist James Baldwin. Baldwin set a formidable example of self-discipline and artistic integrity. He encouraged Parks to find her own voice and to explore writing for the theater. At the end of the year, Baldwin called Parks “an utterly astounding and beautiful creature who may become one of the most valuable artists of our time.”

Following Baldwin’s advice, Parks educated herself in the art of the theater. After graduating Phi Beta Kappa from Mount Holyoke in 1985, she spent a year in London studying acting, not with the aim of pursuing an acting career, but to deepen her understanding of the stage. Returning to the United States, she settled in New York City, working secretarial jobs by day and churning out one-act plays by night. She haunted the small theaters of Off-Broadway and Off-Off-Broadway and produced her first plays in bars and coffee houses. A chance encounter with Village Voice theater critic Alisa Solomon led Parks to an association with the Brooklyn Arts and Culture Association (BACA). It marked the beginning of a fruitful collaboration with director Liz Diamond, who directed Parks’s first full-length play, Imperceptible Mutabilities in the Third Kingdom, at BACA in 1989. Described as a “choral poem” of African American history, cast in metaphors drawn from the life sciences, Mutabilities brought Parks immediate acclaim. Critics praised her uninhibited, imaginative language, and highly original stage imagery. The play won Off-Broadway’s Obie award for Best New Play.

In 1991, Parks became an Associate Artist at the Yale School of Drama. Her work attracted support from the Rockefeller and Ford Foundations, as well as the National Endowment for the Arts. Her next play, The Death of the Last Black Man in the Whole Entire World (1992), also premiered at BACA, but her work was quickly spreading to theaters outside New York. In the same year, her play, Devotees in the Garden of Love, debuted at the Actors Theatre of Louisville.

Suzan-Lori Parks had also captured the attention of playwright and director George C. Wolfe, whose work — particularly his 1986 play, The Colored Museum — had close affinities with her own. When Wolfe was named to head the New York Public Theater in 1993, he was eager to schedule a new play by Suzan-Lori Parks. Her association with the Public began with a production of The America Play, directed by Liz Diamond, in which Parks first introduced the notion of a black man who works as an Abraham Lincoln impersonator, an idea that recurred in her later work, Topdog/Underdog.

Her 1996 play, Venus, wove a fictional narrative around the true story of a 19th-century African woman, known as “the Hottentot Venus,” who was exhibited as a curiosity, caged and naked, in Europe in the early 19th century. Venus opened at New York’s Public Theater to intense publicity and won Parks her second Obie Award. That same year saw the release of a feature film written by Suzan-Lori Parks, Girl 6, directed by Spike Lee. The playwright’s imagination continued to range over a panorama of literary and historical topics. For a number of years, she had contemplated a re-interpretation of The Scarlet Letter, Nathaniel Hawthorne’s tale of adultery and atonement in Puritan New England. Her inspiration eventually produced a very different story. In the Blood, produced at the Public Theater in 1999, tells the story of a homeless woman with five children by five different fathers.

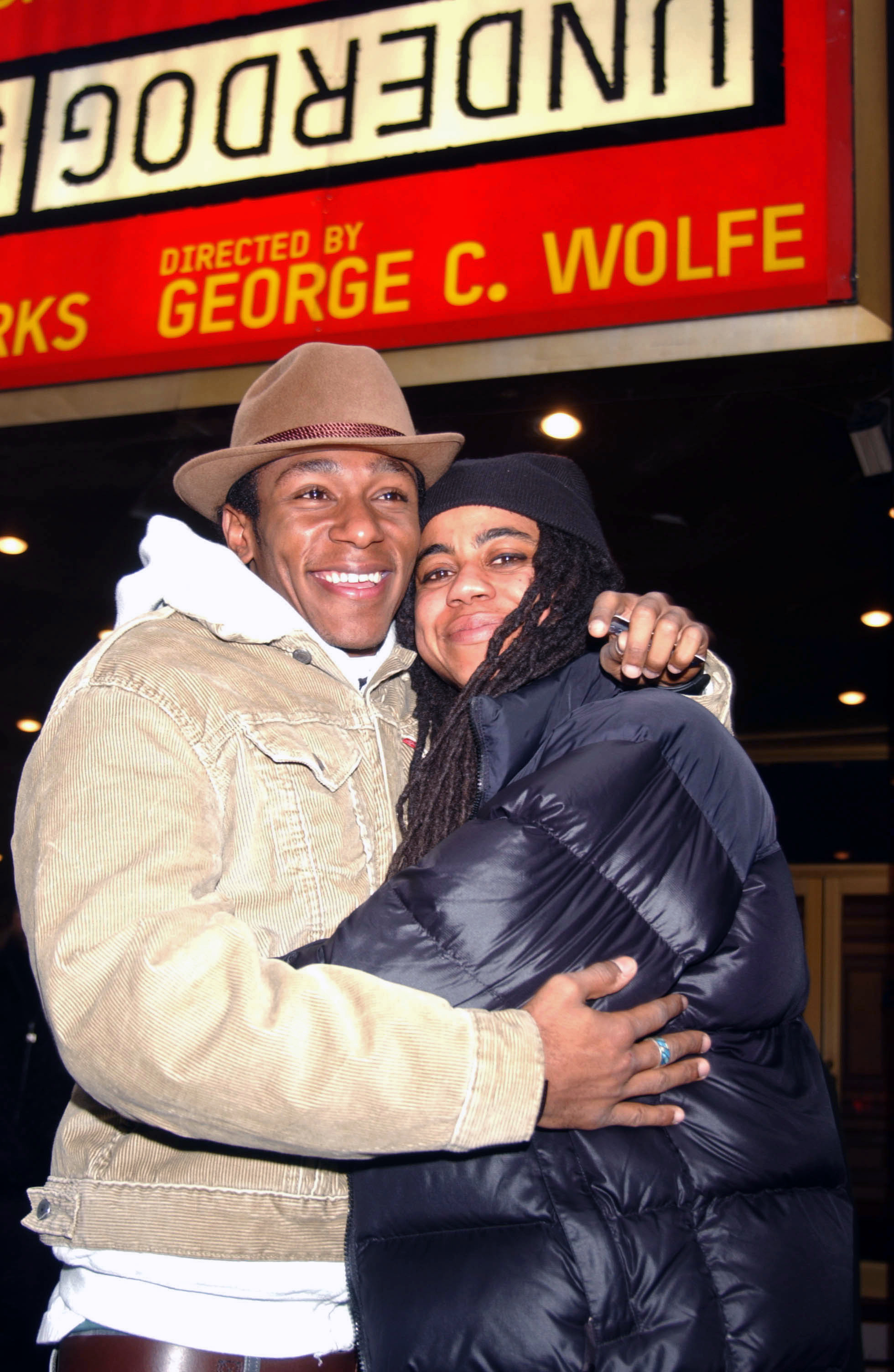

Topdog/Underdog marked something of a departure from the exaggerated language and surreal imagery of the playwright’s earlier work. Set in a single room, it explored the conflict between two brothers, ominously named for President Lincoln and his assassin, John Wilkes Booth. It opened at the Public in 2001 with actors Jeffrey Wright and Don Cheadle as Lincoln and Booth, directed by George C. Wolfe. After a sold-out run at the Public, it moved to Broadway’s Ambassador Theatre, with rapper and actor Mos Def replacing Cheadle as Booth. In 2001, Parks received the coveted “genius grant” of the MacArthur Foundation. Topdog/Underdog was awarded the 2002 Pulitzer Prize for Drama. Suzan-Lori Parks was the first African American woman to be so honored. Time magazine named her one of its “100 Innovators for the Next New Wave.”

After the success of Topdog, Parks moved to Los Angeles for six years, where she broadened her creative activities and taught a graduate playwriting seminar at the California Institute of the Arts. While seeing nine of her full-length plays produced, Parks has not confined her efforts to the live theater. In Los Angeles, Parks wrote a television adaptation of Zora Neale Hurston’s novel Their Eyes Were Watching God (2005), produced by Oprah Winfrey, and starring Halle Berry. Her own book, Getting Mother’s Body, a Faulknerian “novel in voices” set in West Texas, was published in 2003. Her adaptation of the classic opera Porgy and Bess, which premiered on Broadway at the Richard Rodgers Theatre, won a Tony Award for Best Musical Revival in 2012.

At the same time, Parks undertook her most ambitious theater work to date. She set herself the daunting task of writing one complete short play every day for a year. She held herself to this rigid program while fulfilling a demanding travel schedule, writing in hotel rooms and even while waiting in airport security lines. The resulting work, 365 Plays/365 Days, was produced by 700 theaters around the world, in venues ranging from street corners to opera houses. With major theaters in the largest cities acting as “hub theaters,” coordinating the efforts of smaller groups throughout their metropolitan areas, it is the largest grassroots collaboration in theater history.

She followed this massive project with Ray Charles Live!, a stage musical based on the life and music of the late Ray Charles. She has since completed two more plays, Father Comes Home from the Wars (Parts 1, 2 & 3) — an epic set during the Civil War — and The Book of Grace, and is reportedly at work on a second novel. Meanwhile, she is in constant demand on the college lecture circuit. In 2015, she received the $300,000 Dorothy and Lillian Gish Prize, awarded annually to artists who have had an extraordinary impact.

In 2022, Parks, 59, has four productions in the Fall. A 20th-anniversary revival of Topdog/Underdog, Sally & Tom, a new play about Parks’s two favorite subjects, history and theater, but also about Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings, Plays for the Plague Year, Parks’s diaristic musings on the first year of the Covid-19 pandemic and a coincident string of deaths, including those of Black Americans killed by police officers, and The Harder They Come, her musical adaptation of the 1972 outlaw film with a reggae score.

Suzan-Lori Parks currently teaches playwriting at the Tisch School of the Arts in the Department of Dramatic Writing at New York University. During the 2016-17 season, she was the Signature Theatre’s Residency One playwright. She launched her residency with her play The Death of the Last Black Man in the Whole Entire World AKA The Negro Book of the Dead, a “historical nightmare with hypnotic staging.” Her play White Noise portrays the complicated relationships of a quartet of Americans, black and white, who have been friends since college, and the course their lives take when one becomes the victim of a police beating. White Noise opened to rave reviews at New York’s Public Theater in 2019.

Suzan-Lori Parks’ Topdog/Underdog won the 2023 Tony Award for Best Revival of a Play at the 76th Annual Tony Awards. It previously earned two 2002 Tony nominations, including Best Play, and won the 2002 Pulitzer Prize for Drama, marking Parks as the first Black woman to achieve this honor.

In her 2024 play Sally & Tom, Suzan-Lori Parks explores the complicated “relationship” between Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings, who was 14 when Jefferson began a sexual relationship with her. The play combines this historical story with a modern narrative about Luce, a Black female playwright, and her white director husband, Mike. They struggle with how to honestly depict Jefferson and Hemings’ relationship in their first major theater production. Directed by Steve H. Broadnax III, the play prompts the audience to think deeply about intimacy and power, questioning simplified historical accounts. It aims for a truthful representation of history, reflecting Parks’ focus on the subtle complexities of past injustices and intimacy through theater. Parks describes this process as an opportunity to wield “vulnerability and introspection” as superpowers.

Suzan-Lori Parks lives in New York City with her husband, guitarist Christian Konopka, and their son Patrick.

The most exciting and acclaimed playwright in American drama today, Suzan-Lori Parks is the first African American woman to win the Pulitzer Prize for Drama. Audiences across the country relish her rich blend of fantasy, humor, history and legend, bursting with the music and wordplay of African American vernacular speech. The powerful theatricality of her work forces audiences to re-examine their thinking about race, sex, family, society and life itself.

Her plays Imperceptible Mutabilities in the Third Kingdom and Venus both won Off-Broadway’s Obie Awards for Best Play. In Topdog/Underdog, written in only three days, two brothers named Lincoln and Booth work their way through a dense undergrowth of family grievances, until their names take on an awful relevance. A sensation at the Public Theater in 2001, it moved to Broadway the following year, bringing the playwright a MacArthur Foundation “Genius Grant” and the Pulitzer Prize.

Another writer might have choked on the expectations raised by her success; Parks responded by writing one short play every day for a year. The resulting work, 365 Plays/365 Days, has been produced by a network of 700 theaters around the world, in venues ranging from street corners to opera houses. It is the largest grassroots collaboration in theater history. How does she explain her extraordinary productivity? “Discipline,” she says, “is just an extension of the love you have for yourself.”

Thank you for being here today.

Suzan-Lori Parks: Thanks for having me.

Topdog/Underdog has been your most acclaimed play to date; it won the Pulitzer Prize. Let’s talk about that play and the relationship between the two brothers. One of them was a three-card monte player.

Suzan-Lori Parks: There are two brothers in the play. It’s a two-hander. Two brothers, Lincoln and Booth, African American men, in their 30s, kind of, and one is a booster, meaning he goes out and steals things. What do you call it? Shoplifts things, putting them under his coat and whatnot. And the other gentleman works as an Abraham Lincoln impersonator in an arcade where people come in and shoot him. It’s complicated. So he works as a Lincoln impersonator, but he used to throw cards, meaning he used to do three-card monte, like the shell game, but with playing cards. He used to throw cards on the street, and he was the best that ever lived. He felt one day that that was going to be his death, so he swore to never touch the cards again.

The difficulty in the play is that he’s remembering himself basically. Through the course of the play, this young man remembers who he is, and what his calling is, and he is called to throw the cards again. It proves to be very difficult for him. If he could just not remember who he really is and keep on impersonating Abraham Lincoln, he would be all right. But it’s not enough.

He’s sort of dragged down. There’s a force like gravity, isn’t there?

Suzan-Lori Parks: It is almost, or drag almost. He’s pulled into himself. He’s literally “re-minded.” He remembers who he is.

Was Adam reminded of who he was? Adam like the “Adam-in-the-Bible” Adam. Was he reminded? Is that what the snake did? Did the snake remind him of who he was? So was he dragged down into his own humanity and to his own — what do you call it? Mortality? Because that’s what happens to this gentleman, Lincoln, in Topdog/Underdog. He is reminded of his own self, which means — that’s right, ’cause Adam ate from the tree of life and learned about death. And that’s what it is. He’s reminded of himself, so he moves from the historical into life. Anyway, when I think about the play, then I start going, “Woo!” but I don’t really think about it that much.

There seems to be almost a cosmic aspect to these brothers, because somebody named them Lincoln and Booth.

Suzan-Lori Parks: Their father named them that. Their father named them Lincoln and Booth. It was a joke, Lincoln is the older brother, and Booth is the younger. Their parents had a very difficult relationship, and they have been on their own for a long, long time and have had to make their life, just the two of them. But their father named them as part of a joke.

Maybe names aren’t something we should fool around with that much.

Suzan-Lori Parks: They have power. They have a lot of power, as does name-calling. There’s a lot of that in the media these days, people calling people things, mostly unkind things, and who has the right to call who what? Context is everything — everything. We have to be aware that names have a lot of power.

What was it about Lincoln, as a historical figure, that captured your imagination?

Suzan-Lori Parks: What is it about Lincoln that hooks me first? It’s his costume. That’s not irreverent or dissing Lincoln. You know what I’m saying? It’s his costume: the hat, the beard, the height. This is from a person who as a child was very drawn to mythic characters. So the hat, the beard, the height, I think that that has burned itself in the imagination of the universe in a very deep way, and even if he had been just — I don’t know. Then the other things around it I think — I don’t know — but I think that we can’t dismiss that, because all the world’s a stage, and the costume is very, very important. And he freed the slaves and whoo! You can imagine that. There they go, running free.

You know, he spoke in a high voice. That is always a little piece of the puzzle that makes me go “Hmmm.” How high was his voice? Can you imagine a man that tall speaking like this? They say in some African countries that the dead speak in nasal tones, and I always find that fantastic that he had a high voice. And he was shot in a theater by an actor. That’s what draws me to him a lot, also. Costume? Free the slaves? That’s icing on the gravy. Shot in a theater by an actor. How good is that? If you’re a playwright, it just doesn’t get any better than that.

You mentioned Adam in the Bible. There is almost a sense in your play that the historical Lincoln was destined to be shot by Booth, that there was almost a sense of original sin, maybe that he was too pure for this world, that there was an inexorable tragedy that was going to come.

Suzan-Lori Parks: I think that’s another reason why he captures us. These are things that we overlook in the things that are listed in history books. We forget these deep things that are the same reasons why music affects us in a certain way. You play a certain note, you feel a certain way. We forget these things, these things that resonate that we can’t quite quantify. That’s one of them. It’s almost as if we, or he, knew his end, which is one of the deep great things. It’s why the Greeks loved to go see Oedipus. They knew the end. There is something deeply satisfying in that, like dawn or nightfall. You know where it’s going, and there’s something incredibly satisfying in the human structure that needs that and enjoys that. I think you’re right. I think there is something in him that knew that. He was the one who kept the country together, but a part of his destiny was to be blown apart. The costume and the hat and the theater, it’s too good. But I think he knew. I think he knew, and he was part of the pageant. I think he got that, and that is why we connect with him. Do you know what I mean?

The same way with John Lennon. His costume wasn’t quite as elaborate and dramatic and amazing, but I think he had an awareness of himself as part of the pageant. I think that’s why we connect to people like that. I think you’re totally right about Lincoln, but that’s not what people want to hear. “Talk about how he freed the slaves and stuff.” Well, that was part of it, but it wasn’t the deep thing, you know. It wasn’t the deeper or bigger thing.

What was the experience like, writing Topdog/Underdog? Was it different in any way from your other plays?

Suzan-Lori Parks: Yeah. It was like silver liquid being poured in the back of my head. That’s what that was like.

Usually, it’s just like I can hear talking. Topdog was like — I thought that if I looked up — I didn’t, as I was writing, because I wrote for three days, or 72 hours. People said, “Well, you wrote from this day to that,” but it was like a three-day period. Wrote, wrote, wrote, wrote, and I thought if I looked up, I would see someone pouring silver liquid into the back of my head. That’s what it felt like. It was just like “I know.”

That’s one of those bricks, those story bricks. The lesson from that is: I am not a three-day writer. Though I was, just that once.

A few years ago, you had this idea to write 365 plays in 365 days. You’ve described it as almost like a prayer to the theater, or to art. How did that come about? It’s still going on.

Suzan-Lori Parks: It is. The production is still going on. The production started in November 2006 and will continue through November 12, 2007. My husband, Paul, was there when it sort of came, from the great prompter who stands off stage, continually whispering things in my ear.

We were hanging out at our house in Venice Beach, and I said to Paul, my husband, “I’m going to write…” and I talked in this voice, which is funny, because maybe the nasal tone thing — Oh, it gets kind of creepy! “I’m going to write a play a day, and I’m going to call it 365 Days/365 Plays. Wow!” Paul wears his sunglasses — his shades — all the time, because he’s a blues musician. He’s sitting on the couch like this, and he goes, “Yeah, baby. That’d be cool,” like that. I said, “I’m going to do this,” and he said, “That’d be cool.” There it began. I ran upstairs and started right then. It was the 13th of November 2003, I think, or maybe 2002. I can’t remember. Anyway, 2002 or 2003. And I wrote a play a day.

The first one was called Start Here. It’s about Krishna and Arjuna and their starting, their beginning. Arjuna, the human, he doesn’t really want to do it. He’s scared, and Krishna the god is saying, “Oh, come on. I can hear them writing your name in the book. Let us go forward.” Every day after that, I just wrote a play a day, and now we’re doing it in, gosh, I think it’s 14 or 15 different networks in this country and abroad, each with 52 theaters. Each of these 14 or 15 networks around the globe each have 52 theaters, and simultaneously, they’re doing the plays. So there’s hundreds and hundreds of theaters. My producer, Bonnie Metzgar, is a genius at bringing people together. We’re so smiley about this. We’re charging a dollar a day for the play, so we’re making no money, hand over fist, and we’re having a ball.

One effect is that some of the bigger theater companies, who are kind of up on the hill, are joining hands with smaller community-based companies. They don’t usually have a lot of contact, and now they’re coming together. So in a way, you’re bringing the theater community together. Was that intentional?

Suzan-Lori Parks: Not in the writing of it. I have nothing to say. I have things to show.

I just wanted to say thank you to theater for being. I wanted to say thank you, and the way I say thank you is by writing in the way I wanted to. I wanted to embrace the everyday occurrence. I would wake up in the morning and say, “Oh look, there’s a rabbit running across the lawn.” Hopping, I suppose. “Oh, the play for the day is called Rabbit,” for example. Or perhaps a writer or someone had died. I’d wake up in the morning and hear that Carol Shields, the wonderful writer, had died, so there’s a play for Carol Shields, or Johnny Cash or Idi Amin, and they would get their tribute plays. Or I’d wake up in the morning and think, “Oh, I want to write one of my project plays,” I call them. So I’d write Project Ulysses or Project Macbeth or Project Tempest. Or “Oh, I think I’ll write Hamlet. Hamlet is a great play, and The Hamlet is a great novel by William Faulkner. Put them together and write Hamlet the Hamlet.”

I would embrace the great enormous “whatever” by writing. I just wanted to say thank you, and I say thank you by writing. So all these theaters coming together, and the small theaters working with the large theaters and people going, “Oh my gosh, for the first time, we can cast Latin American actors or Chicano actors, because we’re experimenting and we’re having fun.” It’s amazing.

Sometimes they’re done as curtain raisers, and sometimes they’re the whole show.

Suzan-Lori Parks: Exactly. Sometimes they’re done as little features in the lobby while folks are coming into a mainstage production. The City of Seattle is doing a play a day. Every single day, they’re doing the play that was written on that day. It rains a lot in Seattle, so a lot of the pictures that I’ve seen, they’re doing it under a series of umbrellas. It’s gorgeous. Each city is doing them in their own fashion, as they choose, because we really wanted the individual cities to take charge. In Washington, D.C. they’re doing them, and in Atlanta, Chicago, the Northeast. They call it “The Storm Front,” because the show will move from Boston to Connecticut. It will move like a storm front. People are having fun.

In a way, you’re sort of demystifying playwriting by saying, “I can write a play a day.”

Suzan-Lori Parks: Exactly, which doesn’t make it any less incredible somehow.

It doesn’t make it any less like, “Wow,” by saying, “I can write a play a day, and so can you, and so can you, and so can we all.” Or a poem. A lot of people have said, “I’m going to write a poem a day.” Great! Or a lot of folks coming up, younger writers, have said, “I’m going to do it, too.” Great! So they feel empowered. It doesn’t make it any less special. What’s that saying in Zen meditation? “Before enlightenment: chop wood, carry water. After enlightenment: chop wood and carry water.” So it doesn’t make it any less special. We’re just trying to say it’s out there. It’s available to everyone. It’s something that everyone can do. We open up the window of opportunity in your mind, and we’re not necessarily encouraging everybody to become a playwright, but we’re encouraging everyone to open up the window of opportunity and see what happens.