Dancing was getting inside my body, emotionally as well as physically. At the dress rehearsal... I suddenly was in the real atmosphere of the theater. I felt all this sort of dust, or feelings of people who had been there before. It was palpable. And I just thought, ‘this is what I wanted to be.’

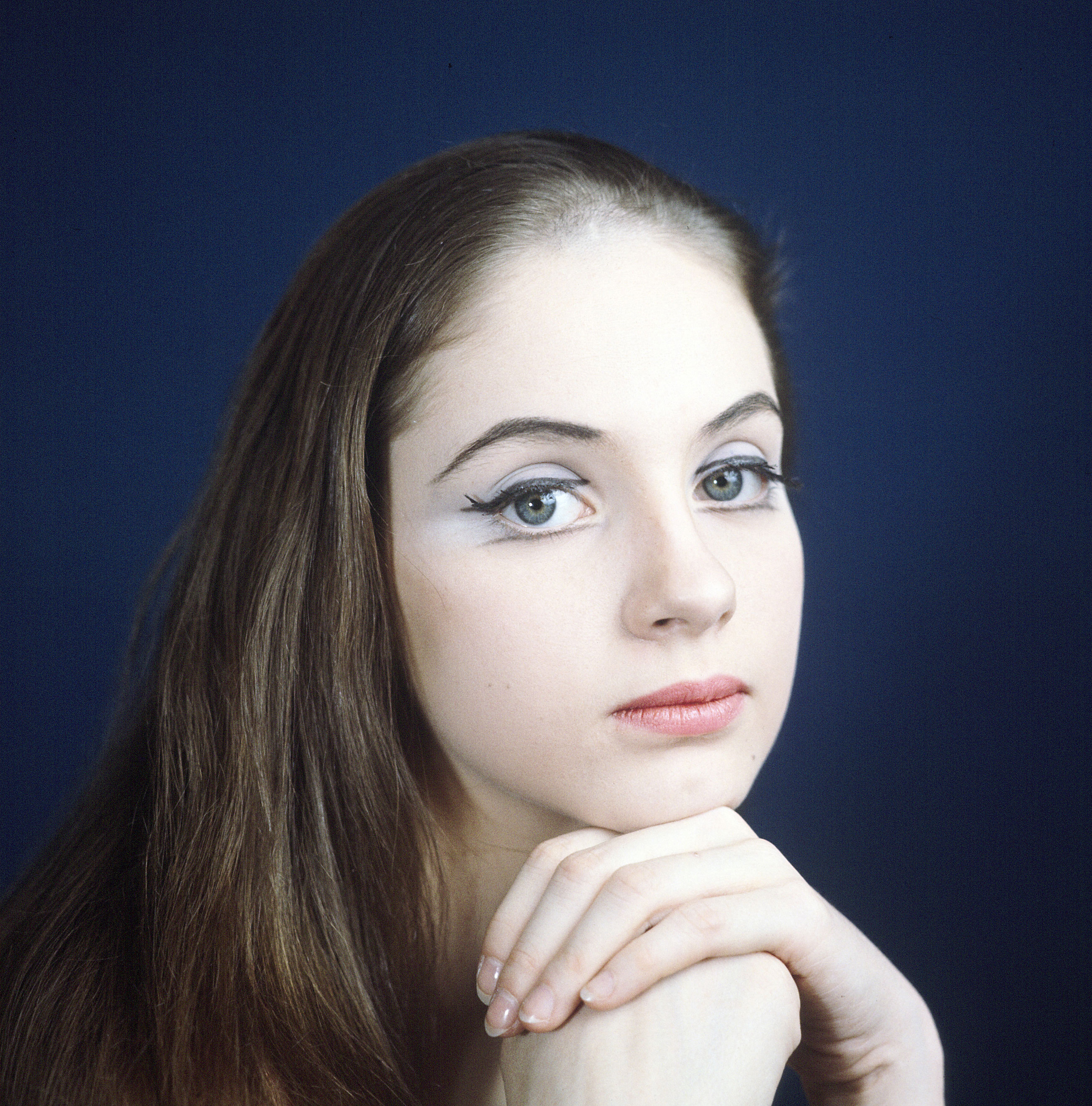

As a child, Roberta Sue Ficker of Cincinnati, Ohio never dreamed of becoming Suzanne Farrell, the youngest ballerina in the history of the New York City Ballet. A devotee of tree climbing, dodgeball and playing “dress-up,” she imagined instead that she would work as a clown. Her study of dance began at age eight when it was decided ballet classes might make the little “tomboy” more ladylike.

Her passion for the art was not instantaneous. Tall for her age, she played boys’ roles in school recitals, and preferred tap and acrobatics to ballet, but finally graduated to a tutu at age 12. After her parents divorced in 1954, her mother worked as a nurse to support her three girls, who were constantly practicing and rehearsing at the Cincinnati Conservatory of Music.

In 1959, Diana Adams, a star dancer of the New York City Ballet (NYCB) and the discovery of choreographer George Balanchine, toured the country scouting talent for the company’s School of American Ballet. Young Suzanne, 15 years old, was selected to audition for the legendary Balanchine. After winning a Ford Foundation Scholarship to attend the School, she relocated with her mother and sister to a one-room apartment on New York’s Upper West Side.

She began by performing an “angel” role in The Nutcracker along with the other students. At the beginning of the 1961-62 season she joined the corps de ballet of the company. By that summer, she was dancing featured roles. Choreographer John Taras was the first to create a role especially for Farrell in Arcade, which premiered in 1963 with music by Igor Stravinsky. Several weeks later, she danced the lead role in a new Balanchine/Stravinsky collaboration, Movements for Piano and Orchestra. She also danced leading roles in Agon, Orpheus, and Liebeslieder Walzer.

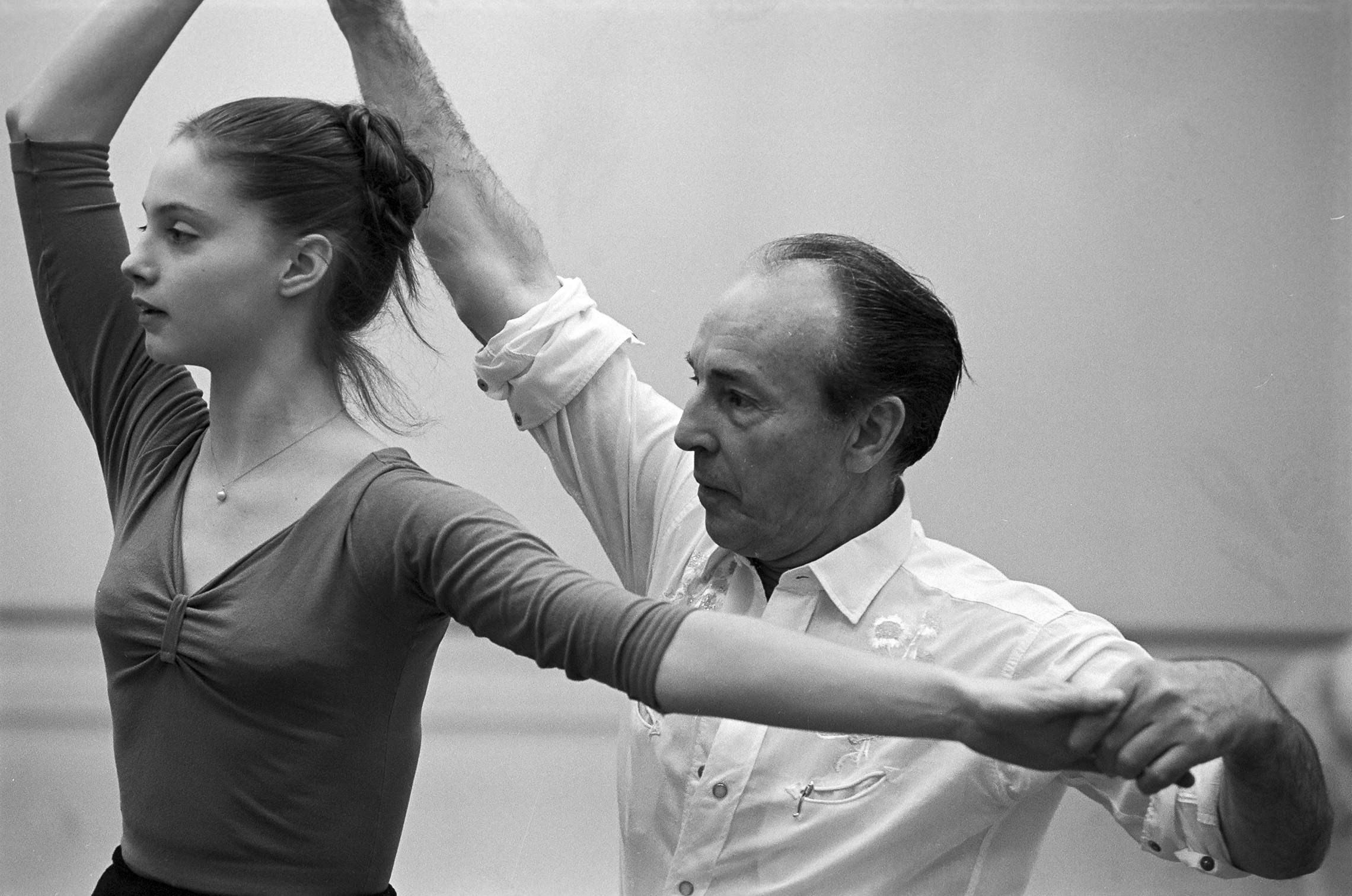

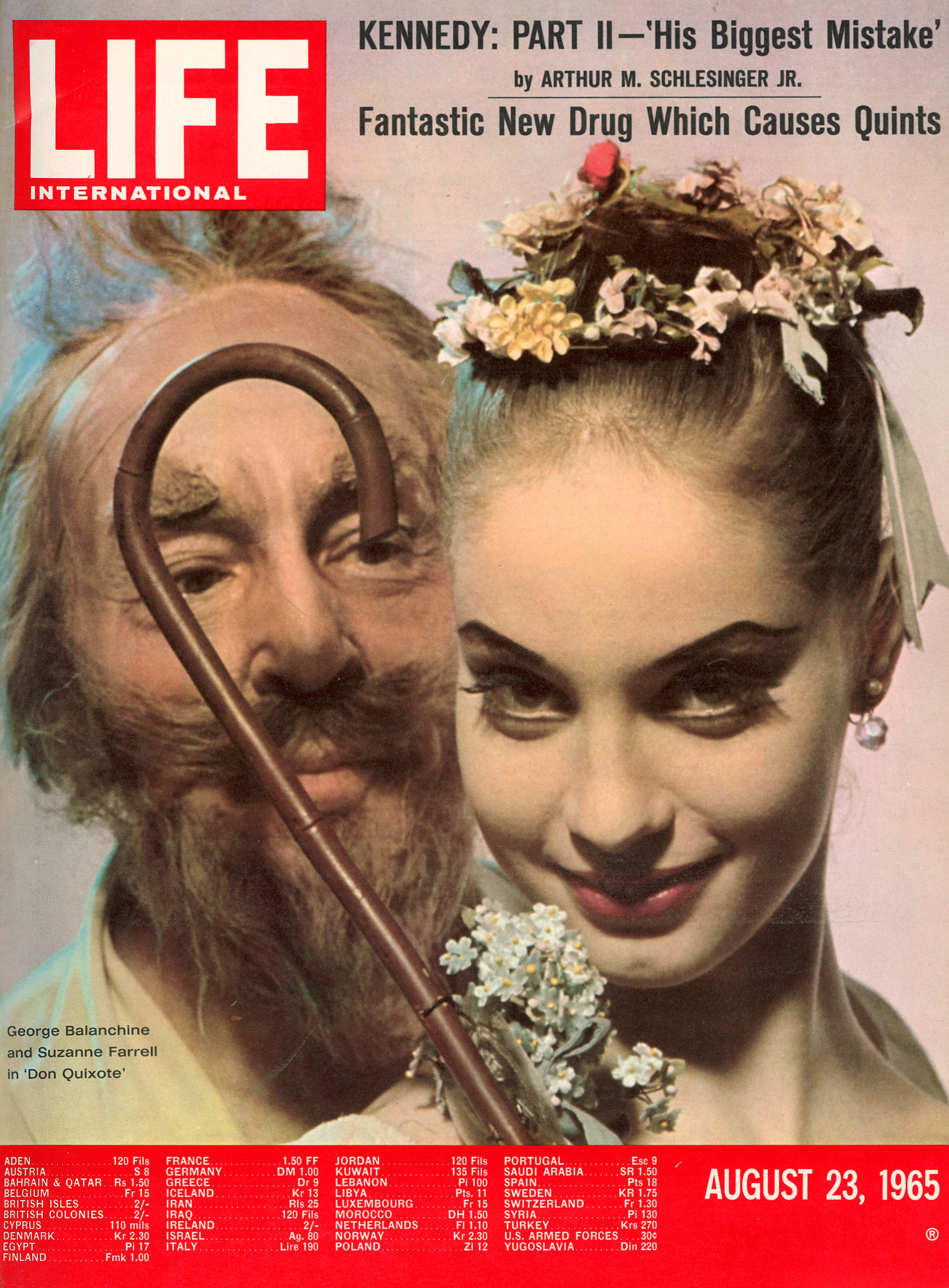

Reviewers began to take notice not only of her long, slender body and impeccable technique, typical of the Balanchine-trained dancer, but of her special personal lyricism and spontaneity. In 1965, Balanchine choreographed a new full-length ballet on the theme of Don Quixote, to a new score by his fellow Russian exile Nicholas Nabokov. Farrell’s performance of Dulcinea, the idealized dream woman of the addled knight, made her a star. The choreographer had created the role especially to take advantage of her magical, mysterious qualities. He was often quoted in the press as saying of his youthful protégé, “She is my muse.” Don Quixote is considered by Ms. Farrell as her breakthrough ballet in terms of pure emotional honesty on stage. This stunning production sealed the unique bond between the young artist and her inspired mentor “Mr. B.”

In 1965, before European and Middle Eastern tours, Ms. Farrell was promoted to principal dancer. In 1966, she undertook her first leading role from the classical repertoire, the Swan Queen in Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake. This was a version in which Balanchine combined modern inventions of his own with the traditional staging he had learned at the Russian imperial ballet school as a young man in St. Petersburg. Critics now praised her growing maturity, especially in her signature role in Don Quixote. Between seasons, she taught at the University of Cincinnati. In 1967, the NYCB version of A Midsummer Night’s Dream was filmed by Columbia Pictures.

When Farrell married Paul Mejia, another young dancer in the company, relations with Balanchine became strained, and the newlyweds left the New York City Ballet. Ms. Farrell began a second career at Ballet of the 20th Century, the Brussels-based company of the controversial Belgian choreographer Maurice Bejart. Bejart’s lavishly designed, theatrical works were the polar opposite of Balanchine’s cool, abstract, contemplative approach. The first collaboration was in 1970, a pas de deux entitled Bach Sonate. It was followed by many others, including Romeo and Juliet, Fleurs du Mal, Rite of Spring, Bolero, and their two most successful projects, Nijinsky, Clown of God and Le Triomphe.

In 1975, Farrell returned to the New York City Ballet. She and Balanchine collaborated on Chaconne, Vienna Waltzes, Union Jack, Tzigane, Davidsbundlertanze, and his final masterpiece, Mozartiana, The last two ballets Balanchine choreographed were solos for Farrell, ten months before he died in April 1983. That same year, while on a European tour for the Chicago City Ballet, Suzanne Farrell began to experience intense pain in her right hip. Suspecting a pulled muscle, she continued to dance, but her hip grew steadily worse. Unprepared for the professional diagnosis she finally sought, she could not bring herself to speak the doctors’ word, “arthritis.”

Two years later, by the age of 40, she had tried every treatment available, without improvement. Though physically compromised and often in pain, she continued performing for four years. She experienced more difficulty in walking than in dancing — perhaps a miracle for those moments — but her condition deteriorated, necessitating hip replacement surgery. Suzanne Farrell retired from the stage in 1989.

Following her retirement as a performer, Farrell continued to teach and to coach the dancers of the New York City Ballet in many of the roles she had performed, but in 1993, the new director of the company, Peter Martins, abruptly terminated her relationship with the ensemble that had been her artistic home for over 30 years.

In the years that followed, she traveled the world teaching Balanchine ballets to a new generation of dancers and repaying her debt to the man who made her one of the brightest stars of the international dance scene. She became the répetiteur for the Balanchine Trust, an independent organization founded to oversee the licensing and staging of his ballets. Other troupes she has worked with include the Kirov Ballet, the Royal Danish Ballet, the Paris Opera Ballet, the Bolshoi Ballet and many American companies.

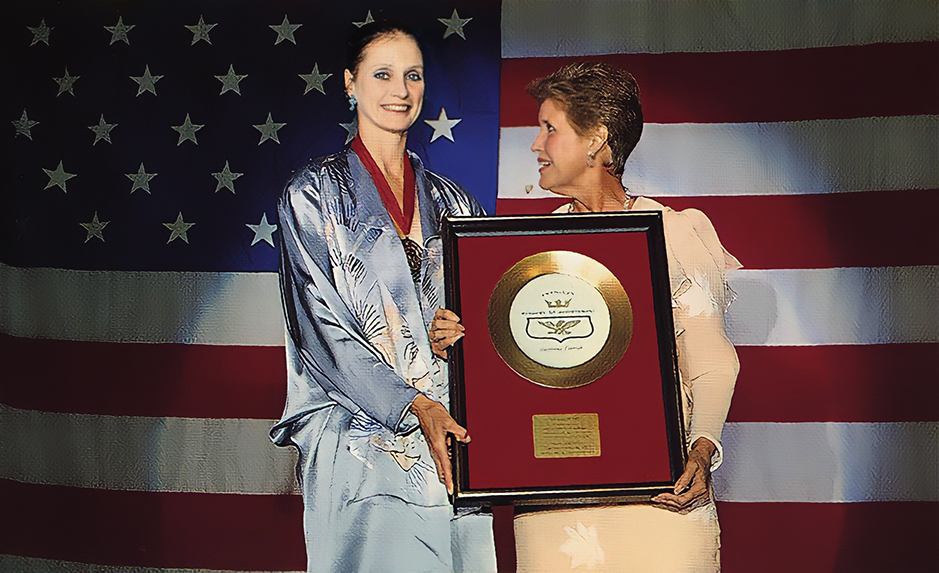

Since the year 2000, Suzanne Farrell has been a professor of dance at Florida State University. In that same year, she organized the Suzanne Farrell Ballet, which became the resident classical ballet company of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington, D.C. For over 15 years, she led the company through performances of many works by Balanchine, including revivals of some of his lesser-known works. In 2003, she received the National Medal of Arts, followed by Kennedy Center Honors in 2005.

In 2006, she solidified her role as guardian of the Balanchine legacy formal with the establishment of the Balanchine Preservation Initiative, created to document and preserve the more rarely performed works of her great teacher and mentor. At the end of 2016, she announced that the following year would be the Suzanne Farrell Ballet’s last season, although she has continued her involvement as teacher and guiding spirit of the Kennedy Center’s expanded dance program as well as her work with the Balanchine Preservation Initiative.

In 2019, following Peter Martins’ resignation from the New York City Ballet, Suzanne Farrell returned to the company after an absence of more than 25 years. The news was warmly greeted by the company’s devotees. The company had endured a period of turmoil around Martins’ departure, and Farrell’s return was welcomed as a sign that the NYCB would regain its full glory, and that the company George Balanchine built would preserve his legacy for generations to come.

“I’m thought of as a cool, unemotional dancer, but inside I’m not. As soon as I hear music, something in me starts to vibrate.”

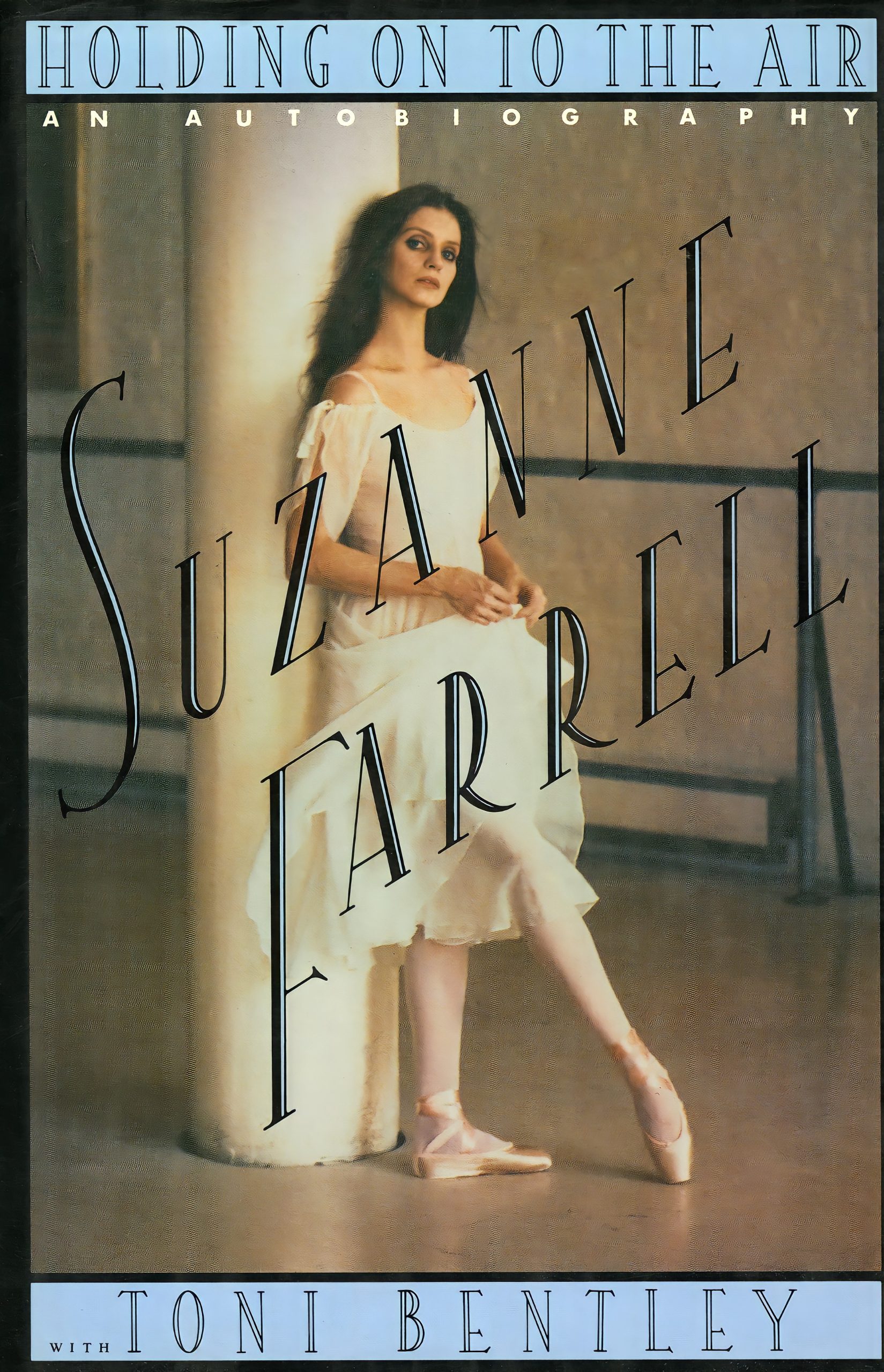

The most lyrical American ballerina of her generation was a young student from Cincinnati when, at age 15, she first auditioned for the legendary choreographer George Balanchine. She danced a section of Glazunov’s The Seasons, humming her own accompaniment, and the perfectionist was charmed. Her talent shone from the moment she joined the New York City Ballet, where she would became Balanchine’s “inspiring angel” and partner in the development of the most glorious ballets of our time. Over the next 25 years, with her artful manner and dignity, she proved that any movement could be unimaginably beautiful and mysterious.

This “choreographer’s ideal,” critic’s dream and public star has been saluted recently as “simply the greatest dancer of our century… and one of the most important who ever lived.”

How did a self-described tomboy from Cincinnati ever adapt to the discipline of serious ballet training?

Suzanne Farrell: My feelings started to change when I realized that dancing was getting inside my body, emotionally, as well as physically. And that it was taking on a whole new dimension, and my life was changing, and I had a performance where I got on stage with an orchestra. At the dress rehearsal, there was no one in the audience, but I suddenly was in the real atmosphere of the theater. I looked out at these empty seats. But I felt all this sort of dust, or feelings of people who had been there before. It was palpable. And I just thought, this is what I want to be. And I knew that dancing would be my chosen profession. And I never regretted it. Never regretted the work. Never got over that feeling. Even now when I go in a theater, it is a very special place to be in. The work, and the responsibility that goes along with it, is very special. I am not afraid of hard work or the responsibility.

There are countless young women who, at the age of five or six or seven, are taken by the hand by their mothers to ballet class. Many young women have this experience but very few continue in dance. Why did you keep dancing?

Suzanne Farrell: I learned to love dance for its own sake. The feeling that it gave me—the happiness, the security, the release of my feelings — it made me a person. It brought out in me the person whom I had the potential to become. I think that’s why I loved it for its own sake, not to be a ballerina. On the other hand, I think it is wonderful for everyone to take ballet classes, at any age. It gives you a discipline, it gives you a place to go. It gives you some control in your life. You are with music. You express yourself in a way that you can’t explain, even to your best friend. And it is in a beautiful environment.

When you get on stage, you can be anything. You are removed from reality in a way, the real world. And yet I think that when you are a performer — and for me, a dancer — is when, to me, that is more real. It is not fantasy. It’s a certain amount of pretending, and your hard work and your training and your professionalism. But it’s more real, because I have spent my life in the theater and on stage, and in the classroom. Far from feeling that it is not the real world, I feel that I see the real world more realistically because I see it clearer when I am dancing.

There was a woman who actually discovered you, Diana Adams. Can you tell us that story?

Suzanne Farrell: I had gone to one audition about a month before I was 14. A Canadian company was coming to perform in Kentucky, and a friend of my mother knew the woman who ran the company, and we thought that maybe I could go and audition, not to be in the company, but to get a scholarship in the school. In Cincinnati, Canada was the “big time.” I wanted to have more knowledge and more opportunities in dance. Mother thought this might be good, so I went down there and I auditioned. And I guess I was a failure, because they were not impressed. So I was going to retire as a dancer. Then the following month, we read in Dance magazine that the Ford Foundation had given money to Balanchine to scout around the country and pick promising students, to have either local scholarships at their own school, or to come to New York. My mother thought this was wonderful, and I decided to come out of my “retirement” and face this audition.

I knew Diana Adams was beautiful because I would go to the library and look at the ballet books and pictures, and I was familiar with this very tall, beautiful image. The fact that she was tall was important to me, because I was very tall, and I had been told in a letter from this Canadian Company that I might be too tall to be a dancer. I used to sleep curled up in a ball because I read you grew at night, and I was afraid I would be too tall to be a dancer. When Ms. Adams came to the studio to watch a class in which we were auditioning, I was very happy to see that she was very tall, so all those fears disappeared for me. When it was over, I don’t know how well I did. She didn’t say anything to us. She talked to the teacher and took her own notes.

I had a program from when I went to see the New York City Ballet in Indiana a couple of months prior to that, and I took it to her, and I asked her for her autograph. And she wrote “good luck” on it. And I thought that she was wishing me good luck, or that she thought I would need it desperately, or I don’t know what she meant. But I took it as a very personal message. Good Luck. And that gave me such inspiration and such trust, so she was the person who eventually suggested that I audition, go to New York and audition for a scholarship. Not that I had one, but the fact that she said “good luck” was enough for me to hang onto, and to consider pursuing my dreams. So we went to New York, and of course I did get a scholarship.

She was a wonderful lady. A very elegant person. I learned a lot from her, not so much in what she said, but in what she didn’t say. She didn’t become overly protective, or say “I think you should do this, or dance that way.” She also told me what she knew when she was teaching class, and made suggestions. I think you can make a better impression by suggesting something to someone than telling them what they have to do.

Who had the most influence on your career? Who had the greatest impact on you?

Suzanne Farrell: That’s an easy question. It was, of course, George Balanchine. He came from Russia via Europe and settled in America in 1933. He started a little company which was not very successful, so he had to start over and over again. Ultimately, he founded the New York City Ballet. I happened to be born at the right time, came to the right place, and had the fortune to audition for him, and work with him, because he is the genius of the century of ballet. I learned how to dance with him. I think he was a great philosopher. He had a wonderful theory that you live in the “now,” which I think is important. Along with living in the moment, you also have to assume the responsibility that goes along with it, and you don’t take your position lightly. But it also means that you get the full value of the moment that you are living, so you don’t look back on your life and say, “If only I hadn’t wasted time, if only I had done this.” You do the best you can. It was wonderful to be able to go home after a performance, and think, well it wasn’t maybe so good, but it was the best I could be at that time. Then you have a departure point and some place to go to for the next time. At least you know you tried your best. There is always some kind of progress, and you learn from that situation.

I learned a lot from him, aside from just learning how to dance. Of course, he was quite a bit older that I was. He was 50 years older than I was. I had the benefit of all his experience, all the ballets he did before I was even born, plus the ballets he did when we were working together, up until he died. It was like I lived his lifetime in my short career as a dancer.

It was a great experience. I think you have to respect time very much, and know the time you are living in and that we are all living at the same time, but we are all at different times in our lives, and you have to see that and make the best of it.

There were ballets in the course of your career that have special importance for you. One was Don Quixote. Can you talk a little bit about that?

Suzanne Farrell: It is a very involved story. As I said, I didn’t read that much in school because I became a dancer and I didn’t have that much time to sit down and read. Nor have the kind of body that would sit still that long. Mr. Balanchine told me that he wanted to do this ballet. He had wanted to do it for quite some time and he felt he had found the person to do it for. It was a departure for him, because it was three acts, and it had a story. It was a novelty for him to do a big three-act ballet with a big story and lots of scenery.

And he created a part for you?

Suzanne Farrell: Yes. I played Dulcinea, his inspiration. It was particularly exciting because the first night he did the part of Don Quixote himself. It was more a character part as opposed to a dancing part. Basically it brought us together in terms of our future collaboration. Up until that point, I still was always in awe of him, and couldn’t say much to him other than “How’s the weather?” “How’s your cat?” or something like that. It really brought us together where our work and our feelings became very important. It was a great ballet. I had a wonderful time. I played many different parts in it.

What did that chance to dance Dulcinea mean to you?

Suzanne Farrell: It was the first time a big ballet like that had been built around me. There were very few dancing roles for our company of 60 dancers. It was basically my ballet, and that of course caused some friction from other people in the company. On the other hand, I also had a job. I was paid as a dancer, and this was my work. He chose me, and living in the moment I was going to get the best out of it. I started to read the book. Couldn’t find myself in the book — a thousand-page book, you know. Finally I went up to him in rehearsal, I had the book, and I said, “I can’t find myself in here, where am I?” And he said, “No, you don’t have to read the book.” So it was the beginning of where I really trusted him. We learned a lot. I believed that anything I needed to know about the ballet would be in his choreography.

From the technical point of view, he started looking at me and asking me to do things that he had never asked someone to do before. It seemed at the time impossible, and yet I realized that it’s not impossible, it’s just different. So “impossible” went out of my vocabulary. I said, “No, I can’t do it today, but let me work on it.” We were always trying and failing, or trying and discovering. When someone believes in you, and you believe in them, it is a very empowering thing to give someone, and a responsibility to have in return. There is just no end to how hard someone is willing to work when you have their belief in you. Technique doesn’t really play as big a part as how you look at the picture, the part that you play in the picture. I learned a lot from that ballet. I also learned how to dance.

There is another ballet that is important to you: Tzigane.

Suzanne Farrell: In the early days of my career, I was always this virginal girl in white. I liked that, but the tomboy in me always wanted to be a little contrary. I used to wish that I could play the black swan instead of the white swan, or the evil girl instead of the good girl. So when I came back to the company, this was the first thing Mr. Balanchine did for me. I was curious to know how he would see me. Tzigane means “gypsy,” it’s Hungarian. I thought he’d give me something very technical, but the first thing he had me do is sort of mosey on stage in this sort of indifferent quality. I thought this was very strange. “I’m not sure if I want to look like this. What are people going to think? They expect me to dance.” And then I said, “No, he’s always presented you very well, and you believe in him. Let’s try something that hasn’t been done before.” So we started working on this ballet. It was a lot of fun to be a gypsy. By then Mr. Balanchine and I had become comfortable with each other, and frequently he would say, “Oh, you know what I want. You fill in.” That was very nice of him, but also a big responsibility. Because it had to look like what he might do, be in the same flavor, and the same character as what he might do, and wonderful that he trusted me enough to say, “Oh, Suzie, you do it.” It was quite thrilling, and gave me a lot of freedom in a world that has a lot of discipline. At one part in the choreography, he said, “Oh just stand here and do something, and then start turning.”

As the ballet starts out, I’m dancing to a solo violin. There is not even a conductor. I don’t even see the violinist. He’s down in the pit, and there is just a single spotlight on my face. The rest of the stage is dark, so it is very lonely. In fact, it is probably the loneliest I’ve ever been. Even lonelier than walking down the streets of New York by yourself. To be in front of people, you have to look interesting, have to go from one side of the stage to the other, portray something, but you don’t even have the sound of an orchestra to fill the void. Just this one lonely violin and myself. I start to dance. And it stays this way for about five minutes. It was a long solo. Just before the ballet changes, and I am supposed to do this step, and pantomime, and then turn like a whirlwind before my partner is to come in, the violinist got carried away, and he started playing extra music, and I didn’t know what to do! So I reached into my bag of tricks, and I put my hand out and I pretended that I was a fortune teller, writing down a fortune on the palm of my hand. And that became the choreography. And now people would look for that in the ballet, but that was not choreographed. That happened at the moment when I had extra music left over and I didn’t know what to do. I couldn’t just stand there and do nothing! And so I said, “Well I’m going to write my fortune.” And that’s what I did and by then it was time for the next part of the ballet. It’s remained in the ballet and has become one of the signatures of that particular ballet. That was a lot of fun.

A lot has been written about it but, in your own words, how would you describe your relationship with Mr. Balanchine?

Suzanne Farrell: He of course was my teacher. He was my friend. I believe also in destiny. I think we were meant to be together. That we both had chosen these professions, he from Russia and me from Cincinnati. It’s so strange that our orbits should intercept. We both wanted to work in ballet. So, we became very close. We were very much in love with each other in many ways. And I think that if it hadn’t been that way we wouldn’t have gone on to do the work that we did. We were both very professional. He could work with other people, and I could work with other people, but it was important in the whole scheme of things that we have this great love for each other. And it was devastating at times, but I tell you, I wouldn’t trade it for the world. I wouldn’t change any of my life. I’d live it all over again the same way.

What are some of the hardships you’ve had to endure along the way, some of the obstacles you’ve had to overcome?

Suzanne Farrell: Well, I’ve had injuries, but I’d always get out on stage because I think the body is a wonderful thing, and you have to treat it with respect. We haven’t even reached our potential for what we can do as human beings. I went through a period where I had hip trouble. I thought it was just a typical pulled muscle, so I used liniment, and warmed up more than I thought was necessary, all the things we learn to do when you have a typical dance-related injury or sore muscle. Over the months, it didn’t go away. In fact, it got worse. Eventually I realized that I had a very serious problem, and it was the first time that dance had let me down. What had been my salvation and my security with my body was abandoning me. This was emotionally and physically devastating.

It took me a long time to admit that I had arthritis, and that it was not going to ever get better. But strangely enough, when I got on stage, I had no pain, because the moment when I was out there was so important and the “now” of the situation was the only thing that mattered, that my body rallied somehow. We have these powers within us, you know, endorphins. The body can do amazing things in a situation when it is really called upon. And so I remained dancing and performing so that I didn’t have the pain. Even though the same movements in the classroom would be painful, somehow in a performance situation it was not. I went several years in that situation, and I was happy, because by then I was told that I would have to have an operation. You can’t dance with an artificial hip. It was important to me to stay dancing as long as possible, because I knew that once I had the operation I would not be able to dance again. So I was happy. I had to curtail and alter my repertoire. I couldn’t do everything that I used to. But I was dancing and I was happy. There were emotional times. I tell my students, “You have to learn to dance even when you don’t feel like it. Because most of the time you might not feel like it.” But the amazing thing is that, when you start to dance, everything seems wonderful, and puts it in perspective.

How did you decide to go through with the operation?

Suzanne Farrell: By the time I admitted that I needed a hip operation, I had denied it for so long that it was a breakthrough to suddenly say, “I need this.” I knew I would probably never dance again, but I had no choice. By that time, I just wanted to be normal. I wanted to walk down the street without limping. I couldn’t tie my shoes. I couldn’t put slacks on. I was the farthest thing from a person who ever could dance and do all those extremely incredible extensions and contortions that we do.

I had no choice and so I had the operation. I was very happy when I went in, and happy when I came out. Because suddenly I saw that I would live my life, instead of watch it go by, which was the way it had become lately in that situation. And so, of course, the doctor said I would never dance again. But I wanted to. But I didn’t think about dancing again, I just thought about getting well. I put all my energies into the moment that I was now living in, and that was getting well. And I thought, if God wanted me to dance, He will let me dance.

As it happened, it was a long process, and slow, and interesting if not as fast-paced as the kind of life I was used to living. Finally I got back on my feet, and I was walking. People were curious to know what was going to happen to me now. I was giving a little speech, which was the first time I publicly admitted what had happened to me, and the reason why I was speaking was because I was a dancer, but I was speaking as a person who may never dance again.

One of the hardest things that I ever had to do was to be in a situation where I suddenly didn’t have any real control or any of the stability or security that I had always with the dancing. But I had just recently gotten off crutches and I was determined to walk up to this platform and give this speech, in high heels, even if I was slightly listing to one side, and tell these people about what it was like to be a dancer. And what it was like to be a dancer who couldn’t dance any more. And I remember I started to cry because, first of all, I wanted to make my point. I could be admired as a dancer, but I also wanted to be admired as a person. And I said to them that I had to work very hard to become a dancer, but now I had to work even harder to get back any little thing, just to be able to walk, let alone dance.

I wasn’t embarrassed by that. It didn’t really matter. I would be the best that I could be with what I had. If I didn’t dance, I hoped that I would have the conviction and the moral commitment and the courage to let go of something that I couldn’t do any longer, and to do the best that I could do with what I had. I think that was very important for me to say. And it works.

I tell my students, “The act of thinking about something is almost doing it.” If you think positively that you can do it, you are already closer than if you didn’t even try to do it. I think it was a big step for me. Consequently, I did get back onstage. I did dance again. In a different capacity, and not with the range of motion that I had, but I got back onstage. Not to prove a point, not to be some sort of oddity, or hero, but because I wanted to quit myself. I had felt that I sort of had the rug pulled out from underneath me by my hip, and that I also knew that I would be better if I had a goal to reach. I didn’t care really, whether I ever got out onstage again, I only knew that I had to try. That I would be unhappy, I would be unhappy if I didn’t try, but I would not be unhappy if I tried and failed. And so, that was my impetus to get out on stage again and to dance again.