How old were you when you contracted polio?

Tenley Albright: I was eleven.

As a girl who had skated, had a normal life, and was very active, how did you deal with the uncertainty? Knowing that you were ill, how much fear did you feel?

Tenley Albright: I don’t remember fear about being sick. The fear I had was staying in the hospital overnight. I couldn’t imagine anything worse. But no one told me how serious it was. In fact, they took the sign “polio” off my door, hoping I wouldn’t realize how sick I was. Looking back, I don’t think I ever knew how sick I was because it never occurred to me that I couldn’t and wouldn’t get better. I feel very fortunate when I think of the number of people in the hospital at the same time who were in iron lungs, and I do feel lucky. Because of that, perhaps I was motivated to make the most of what I could do with that luck. The fear was really wondering if my friends would play with me when I did get out, and did understand what I had had. But it was just about two years ago that something occurred to me that hadn’t until then.

When I was first in the hospital that very first night, they showed me the long needle that they were going to put in my back to do a lumbar puncture to try to make a diagnosis. But nobody told me they weren’t going to put the needle all the way in, and I was scared. At the end of the bed there was a group of maybe six or seven house officers, interns, medical students, all in white coats. And as they were ready they had washed off my back, and were just about to put the needle in. I said, “Could someone please hold my hand?”

Tenley Albright: I remember very clearly now, that those people in their white coats looked at each other, and no one came forward for a long, long time. Finally, one person came forward and let me hold his hand and squeeze it when it really hurt. It wasn’t until just recently that I realized, when someone was talking about the concerns of things as serious as HIV, that nobody understood how it could be communicated or how people could catch the disease. And as long ago as that, it was very similar to some of the things going on now. As a result of that experience, where the person did come forward and hold my hand, and let me squeeze it when it hurt, having the needle go in, in my own field of general surgery, anytime I’ve had to do a procedure on a patient, I’ve always made sure that someone, a nurse, a family member, someone, held the patient’s hand while I was doing the procedure. Because it does help.

Can you talk about the roots of your dedication to master the art of skating, or the art, if you call it that, of surgery?

Tenley Albright: Whatever you do, if you do it the best you can, has a relation to whatever else you do. People have said to me, “What connection does surgery have to figure skating? Aside from the fact that they’re both blades?” I never thought there was a connection, and I certainly didn’t think of it when I began concentrating in the field of surgery. But there is a connection, because of the mental preparation, trying to do your best, expecting a lot of yourself, and learning to expect the unexpected. You have to be prepared, but you still don’t know everything that’s going to happen.

Right now, I’m working on getting some of the basic research I’ve been involved in clinically applied. Sort of bringing basic research to the bedside, so physicians can use it. And in looking back, in skating, everything is step-wise. I can remember taking several pairs of skating tights to the rink because I would get so soaked, falling down again and again and again while I tried the sit-spin. And I remember my mother saying once, “Tenley, let the other children do a sit-spin. Why don’t you try something else?”

The feeling of when you finally do manage not to fall down, when you are trying something new, is such a wonderful feeling that you want that feeling again. And if you have mastered one little thing in skating, then you try the next thing. When you reach a certain level then you are allowed to take a preliminary test, a first test, a second test. If you pass that test you are allowed to go in the little local competition. So it’s step by step by step. And it’s a very good feeling to try hard and see that you’ve done it. And that applies to whatever you do.

I remember asking my father, who is also a surgeon, “Daddy how did you ever dare to do your first operation?” He said, “It’s not a question of daring. By the time you are allowed to do it, you just are so convinced that you know how to do it so well, and you are anxious to.” And of course there again, you are never allowed to do the whole cholecystectomy the first time. You are allowed to put in a skin stitch the first time, and that is quite a pleasure.

One of your skating coaches, Maribel Vinson Owen, said that when you were starting out, you were very much like all the other little girls skating in Boston. What happened inside you that set you apart from the crowd, so to speak?

Tenley Albright: One of the common threads that comes through when people get together for the American Academy of Achievement is: creativity, dare to be different, be true to yourself, don’t be so concerned with what other people think, be more concerned with what you think yourself, and what you dare to do. I think I am still like the other little girls who are skating, because I just got a pair of roller blades myself, the night before last, and I felt like a beginner. I was a beginner. And all those same feelings of being a beginner in figure skating came right back. It’s the excitement of trying something, and having some little tiny success, and sort of knowing that you can do something, I think, that spurs you on.

Creativity is a big part of it for me. I loved the music. In skating, you respond to the music, you forget yourself. When you are comfortable in your medium, you have a way of expressing your feelings. Then you are free to do your own choreography, and make up things. I was always kind of teased for some of the silly things I’d make up in skating, but that was what I really enjoyed: making up new jumps, new spins, making up a program. I even skated to “Barney the Bashful Bullfrog.”

That was a challenge. I remember saying to my grandmother, “I want to skate to this music.” And she said, “What kind of a costume are you going to use for that?” Whatever you like to do, go ahead and do it. Try it the hardest you can and the best you can, even if it’s seeing how big a mud puddle you can jump over. We all know that’s fun. And when you are juggling things, and it works, it makes you want to do it more. That’s the fun of it. No matter how hard things are, how much work, how tough a competition, how nervous you may be, I recommend not using the word “nervous.” because if you say you are nervous, you are. You have to think of yourself as being like a race horse. If a race horse weren’t keyed up for the event, the gates would open and nothing would happen. So it’s important to be keyed up for something in order to do your best. Whatever it is, go ahead and do it. Don’t let anybody tell you it’s not important. You will find that whatever you do the rest of your life will relate to some of those things you did, no matter how young you are, or how much of a beginner you are.

Take us back to a certain day when you invented a new jump or a new spin or a new move, and tell us what that was, how it happened, and what you felt. Can you recall a certain thing you did?

Tenley Albright: It was about four o’clock in the morning. I had discovered that there were two rinks in Boston where, if they hadn’t sold the ice for hockey for the next morning, if I called after ten o’clock at night, they’d let me use the ice and have it all to myself until the hockey game or hockey practice started. So I did that one morning. I carried my own phonograph and my skates, and it was snowing, and I unlocked the back door of the rink. But just before I did, actually, my feet slipped out from under me, flew up in the air. I fell down, all my things around me, burst out laughing and realized there wasn’t a soul around. It was very, very quiet. But I had the ice all to myself that morning. I had been shown where to put the lights on. I could play the music as loud as I wanted, as many times as I wanted.

And I was then working on a number that was to be for an amateur ice show that came up very soon, and it was a witch number. I decided that it would be fun to do some number where there was something big and flowing like a witch’s cape, and I skated to Berlioz, and the chimes were ringing. And I decided I would have a cauldron of dry ice and be mixing my brew. And I thought, well, what moves can I do? And gradually, I sort of felt perfectly free, nobody watching, could do whatever I wanted, could go slamming across the ice on my rear end, or trip over my own feet or anything. And I kept on doing some sort of swirling, swirly things. And I thought I wanted to do something that would take me up in the air as far as I could go, and it would be rather extreme.

So I took off on a forward edge, jumped with my foot wide as far as I could, but then I hadn’t decided what to do. How do I land? While I was in the air I thought, “I need to land as low as I can, but not fall.” So I landed on two feet, then tried another few times, then finally decided that I would combine what we call a drag, which is quite an easy thing, which you may know how to do. It’s going on one foot bent way down, with your other foot dragging on the ice behind you. So I started out the way you do an axel, or an open axle, went as high as I could, and then landed as low as I could in the drag. I called it a witch jump. I used it in that program and had sort of fun with that. That’s how the little moves get started. There’s another one I call my grass skirt step. And that’s simply a lot of very fast brackets, very quickly in a row. The feet move quickly, the upper body stays still, and you sort of twist in the middle.

When you talk about skating, you talk about the creativity and the free-flowing quality of it. Yet, you were really very dedicated and disciplined in mastering the compulsory figures, and there is something about them that is not creative, and is not fun. What about these other components of the tests that you have to get through?

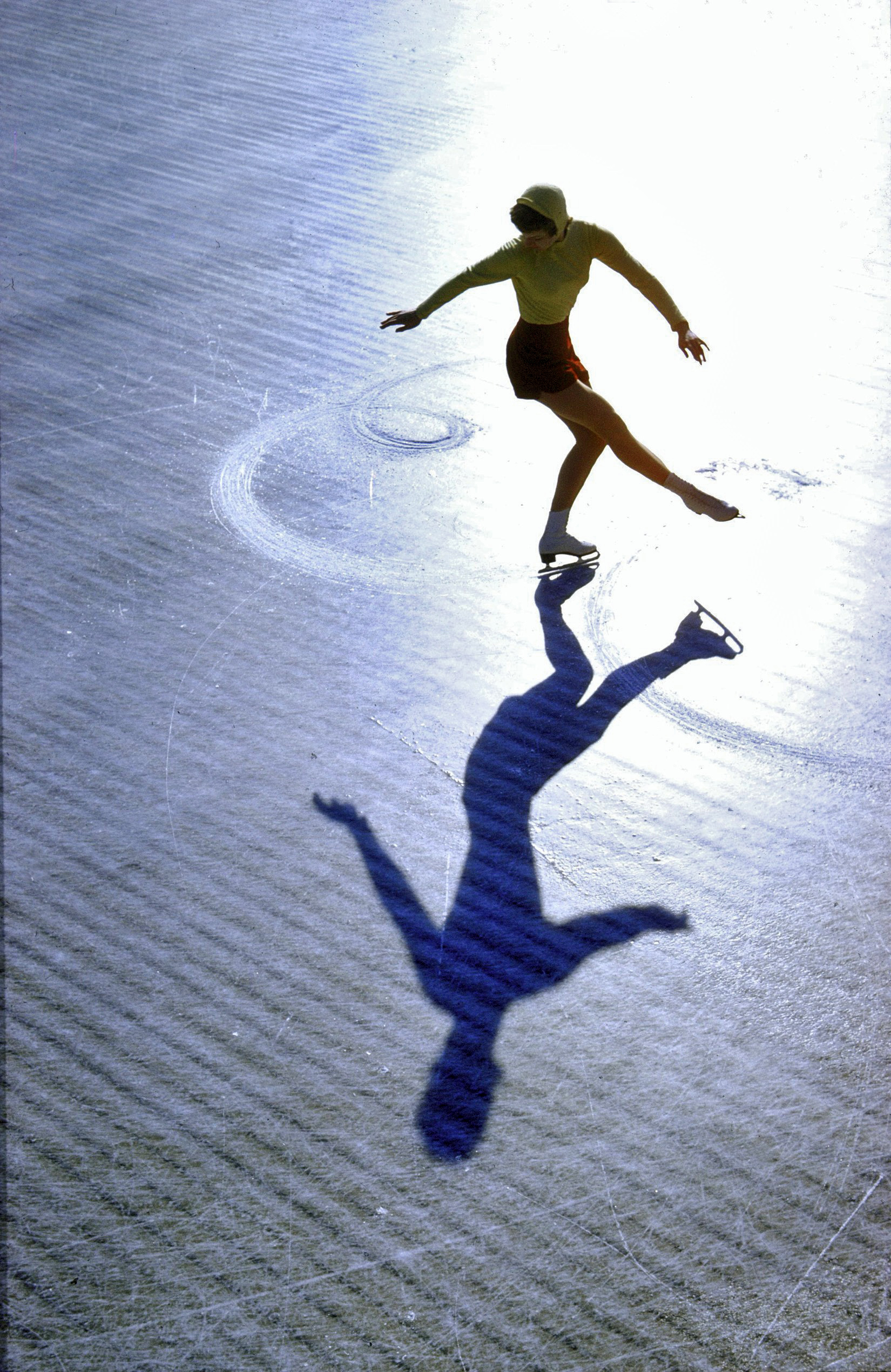

Tenley Albright: I like to think that I was good in the compulsory figures. That wasn’t the part I enjoyed. The jumps, the spins, the dance steps, the choreography and especially that feeling trying to fly, was what I really liked, and what I still like about skating. The compulsory figures… well, there’s the word: compulsory. We had to do them. If you didn’t qualify or come out really high on the compulsory figures, you didn’t have a chance. When the free skating came, you’d be marked too low, so that you wouldn’t have a chance in the free skating. But there is a kind of fascination with those school figures. You are testing yourself. You’re seeing how close you can come, whether you can, in your mind’s eye, draw a pattern on a totally clean, unmarked piece of ice.

Sometimes, when we skated outdoors in competitions in Europe, it would be on ice outdoors that might have snow on it, or sun on part of it, shadow on the other part, and that was really a challenge. You had to be sure that your body positions were right, because you can’t make a circle if you can’t see it, if you are not feeling it. So there was a fascination and a challenge to that. It is a little bit like the barre exercises in ballet.

You seem to have found just the right psychological approach to everything that you needed to do. You made it look so easy. You make it sound easy. You seem to have found, within yourself, just what was needed. And it wasn’t just to be creative, and it wasn’t just to skate. You did what was necessary to become recognized as the best woman skater on the planet.

Tenley Albright: I didn’t work on skating to be the best woman skater on the planet. What appeals to all of us is to do something that is a challenge. I don’t think we’d try if we knew it was easy. If you find something that piques your interest, or that you want to try, you’ve already started it.

Why we accept a challenge, I’m not sure. Maybe it’s part of that feeling of obligation to do what you can, to take part, to have compassion for feelings of other people, whether it’s through expressing your own feelings, or whether it’s caring for them as patients. It’s being involved, it’s testing yourself. I think we need to test ourselves.

If you ever watch a little child, maybe three years old, they love to climb on things, walk on stone walls, test their balance. I still like to do that. It’s within us. I think we tend to teach it out of ourselves. I’ve been lucky because I’ve had a chance to do it in several different areas. But you have to remember that girls were not asked, “What do you want to be when you grow up?”

Now, when I meet these wonderful students who have qualified to be part of the American Academy of Achievement, it’s astonishing to see what so many of them have already accomplished, but also how clearly they know what areas they want to be in. There are a lot more opportunities for young women now, but they also have to make choices, and they are almost required to stick with them in a way. We had sort of a freedom. Yes, we were pioneering in a sense. But now, young women here are asked, “What are you going to do?” and that’s a different type of challenge. And they are certainly accepting it and doing it. In fact, right now, there are a number of the students who were chosen to take part as high school students in the American Academy of Achievement who have now come back and are honorees, who are explaining to this year’s students what they have done since that time, and that’s really exciting to see.

Was there something about your growing up that simply masked the fact that there are human limitations from you?

Tenley Albright: I don’t think any of us really understands the extent of what we can do, and what we are capable of doing. Maybe when I was diagnosed with polio, getting through that, being one of the lucky ones who did get through it, was what changed it for me and made me appreciate things. It made me realize, wow, it’s amazing, we can put one foot in front of the other, we can run up stairs. Another time that occurred to me was when we studied physiology in medical school. I can remember very clearly after our physiology class running up a whole series of stairs outside the main building at Harvard Medical School and thinking, “Whoops! Which muscles are doing what?” And I almost tripped. Again and again, I am reminded that we can do more than we think we can.

One place that really struck me was when I was out on the ice at a competition. My name had been called, and I was standing alone on the ice, realizing it’s my turn, this is it, there is nobody else out here, here we go! And then my music started. And as soon as my music started, I settled right down, felt like responding to the music, forgot that I should be nervous. But I also can clearly remember which ones of my friends were sitting at different parts of the ice. And I was conscious of the surface of the ice, and where there were holes, whether my music was the right speed, whether my foot was in the right position for the next jump, and hundreds of things were going through my mind. And that evening afterwards, I thought, we can’t just think of one thing at a time. Our brains can think of many things at once. We have to realize that. We shouldn’t make ourselves ignore everything. Yes focus, but be receptive to other things. Again and again, we are reminded that we can do a lot more than we think we can. Also, even though it doesn’t always work, we certainly ought to try.

You seem to indicate that by skating as you did at the age of fifteen, you were not only expressing yourself but you were contributing to something. I mean, fifteen year-olds skate, they don’t do surgery. But in a sense of contributing to something, what do you think it was that you contributed to?

Tenley Albright: When I had learned to do certain things skating, and did well in a few competitions, I found that I might be asked to show some of the other children some jumps. Or sometimes at a skating rink, children would come to me and say, “Tenley, will you show me how to do this or that?” And that was really fun, I liked that. And also, a number of things happened that I could never have anticipated. When I won the Junior National Competition at the age of fifteen, I was invited to do all sorts of things that I wouldn’t have had a chance to do otherwise. I was invited to do things like pass out athletic awards for children, and one thing I remember very clearly was the first time I ever visited a reform school for girls. It was quite a moving experience for me.

Because I saw children younger than I was, and my own age too, who had terrible situations, bad luck. Whatever the cause, they had been in all sorts of trouble. But yet, in speaking to them absolutely normally, you could see that there was a common bond. They were just as interested in some of the things I was, and afterwards I was very touched when some of the people who had taken me there told me that some of the girls I had talked to had refused to speak to anybody before that. And I suddenly thought, you know, things like sport are a common language.

And I later saw that at the Olympics, where all the competitors from all over the world were there for the same purpose; you feel as if you know each other. You don’t pay attention to different political backgrounds, or even to language barriers. You feel as if you know each other, and there is a very healthy bond through your sport. So things that you do that have to do with your sport can affect all other parts of your life too.

How long was it between your final competition and your entry into medical school?

Tenley Albright: Just about right away.

What was that like for you? I mean, you were the best in the world at something, and then you were part of 130 young people entering a class. Can you tell us what went on inside you?

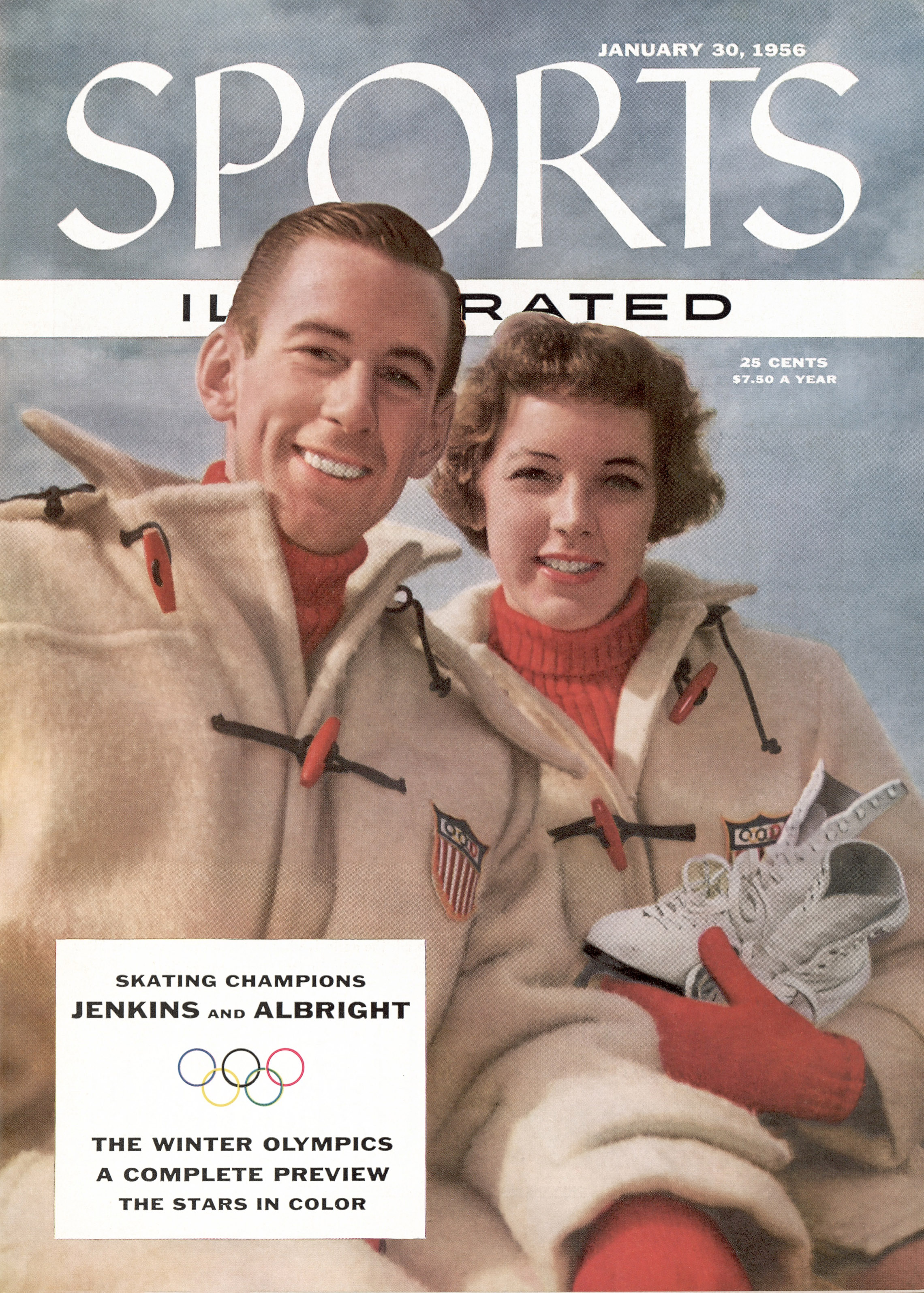

Tenley Albright: I was always motivated to be involved with medicine; I was fascinated. Even when I was deeply involved in figure skating competition, I just knew that what I wanted to do was be in medicine, eventually. After I had been in college at Radcliffe for three years, I felt I really wanted to move on and be in medicine and get going with it. After the Olympic championship in 1956, I applied to medical school. I remember going to the chief of neurosurgery, whom I had met, and asking if there were any requirements that you have to finish college before you apply to medical school. He said, “I thought so, but I don’t know. I’ll check.” So, he checked, and he said, “Well, you know, it’s not written down anyplace.” So I applied to medical school after three years. I had seven interviews at Harvard Medical School.

There weren’t many women in the classes then, and also, I don’t know what they thought of a skater, or someone who had been traveling a lot. Maybe they thought it was all just fun, and I couldn’t settle down, but I did start medical school. September 1 came, and all of a sudden there I was with everyone else. There were 135 or 40 of us in the class, and five of us were women. And everything was new. I had taken everything but science. Of course I had taken the premedical school requirements, but I thought, “iIf I’m going to be studying medicine, I’d better learn everything I can about other things first.”

So when I started medical school, I found myself in the midst of top people from all over the country who had concentrated in all aspects of science. Some of my classmates had taught comparative anatomy. Some of them had done a number of other things before they even started medical school. So once again, I felt like a real beginner. And I’ll never forget those first few months. I read all of the references listed on the back of our outline that had to do with human diseases, and suddenly realized that was supposed to be dessert. I was supposed to be paying attention to all of those dry, uninteresting things that we were supposed to study in those first few months. It was a whole new world. A world I loved, but I found myself very anxious to get to working with patients. And it took me a while to understand that we weren’t going to just start right in there. So it was quite a shock, and exciting, and a challenge again. But as we all know, there are hard knocks in all of those challenges, and it’s not always bruises from falling down on the ice.

Was there ever a time when you were uncertain as to your destiny as a physician?

Tenley Albright: I can remember very clearly after having heard for years about girls going to medical school and taking a place from some deserving man. I can remember after our first exams, that first fall, thinking, where is that person whose place I am taking? And does he want it now? But those were very fleeting thoughts.

I can remember sitting with about six of my classmates, six of the young men at lunch one time, and I said, “Oh, my Gosh! I’ve just gotten a pink slip on our quiz! What am I going to do?” And they commiserated with me. And it wasn’t until a year later that I found out that three others at that same table had gotten those pink slips too.

When you are in the operating room, no matter how spectacular your results, nobody hums the Barcarole for you. Aside from the attention, is there a difference in the satisfaction that you get from your two major areas of accomplishment? Or are they similar?

Tenley Albright: They are similar in inner feelings. In surgery we have something we call “surgical conscience.” Not only must you prepare the patient, prepare your operating team, and be ready for whatever you may find, but also, only you know if you’ve done everything you can to make it as successful as you possibly can. And if you have been creative and you have prepared yourself the best you can in every way, done everything you can for the comfort, the recovery, the cure of the patient, and you can look to yourself, and say, “I know,” that’s a tremendous satisfaction. No words of congratulation or praise can ever match that feeling, when you know you’ve been able to do something for an individual that will add to their life, or even in a small, small way make them more comfortable.

Those are the satisfactions of understanding the effects of your work. What is the surgical mind like? How does it feel as the mind works and you’re doing complex surgery?

Tenley Albright: Part of it is a mind which involves feeling: “I need to address this now.” Ultimately, the decision is mine. I must make it the very, very best I can, and it’s up to me to see that I do. Oftentimes, people think that surgeons are cold, that they don’t talk to patients. I am always shocked when I hear that.

I can remember one night in the emergency ward when the ambulance came, and we didn’t know what we were going to see when the doors of the ambulance opened. What we did see was a very beautiful 16 year-old girl who had been in a horrible automobile accident, and she was unconscious, bones were sticking out of both legs. The scalp flap was off, and blood all over and she was in shock. And obviously, there wasn’t any time to say, “What shall I do first?” Immediately, you just have to put things in motion and handle things — the most acute first: to be sure she was breathing, stop the bleeding, get intravenous in, get the blood pressure back, then splint her legs and so on. And as I was doing that and we got the blood pressure back on her, I was told that her parents had come and could I come out and speak to them. And when I saw that she was stable enough for me to turn away from the stretcher momentarily, I did go and speak to her parents. And as I did, I suddenly felt overwhelmed. My stomach flipped, I felt nauseated. I felt weak, because of the horror of what I had just seen and had to take care of. But I couldn’t let myself feel that way until it was all right to. And that’s part of the surgical mind too, addressing what you need to, and you know you can do, and postponing how you feel about it, thinking only of the patient and what you need to do.

You are a precision performer, and there is nothing in the world that needs to be more precise than surgery. Could you talk a little bit about concentration and awareness of concentration? As you were treating this girl, you were probably not aware of how you were working. Could you talk a little bit about situations where you are not even aware of concentration because you are concentrating so intently? Both in terms of your career as a performer and as a surgeon.

Tenley Albright: There is a very interesting balance, because sometimes when we are intensely concentrating, we also need to have our other antenna up. Maybe what we are talking about is training ourselves to focus on what we need to. Sometimes that seems as if we are blocking out other things, but there is still an awareness of them. I don’t know how really to explain that. But certainly you do that in taking off on a double axel. You have to concentrate on what you are doing, but obviously, if somebody is coming down the ice about to bump into you, you’ve got to be aware of that. But not so much that you don’t think of exactly what you are doing, or you will fall flat on the jump itself.

In surgery, you have to think of exactly what you are doing when the scalpel is in your hand, and your focus is exactly on what it is you are doing. If you aren’t concentrating, and you are not placing that tiny, tiny incision in just the proper point in the common duct, you could be in real trouble, and the patient too. And you can’t allow yourself not to concentrate. But you also have to be aware, so that if something is happening in any other part of the operating field, you sense that too, because you mustn’t ignore that while you are concentrating on this thing. It’s a very, very interesting balance of concentrating and awareness. And our minds are capable of phenomenal things. Perhaps that’s something we should study more and find out about more. Most great people — athletes, scientists, Nobel Prize winners, movie producers — know that they’ve had to concentrate but allow their minds to think in many areas at once. If they didn’t, while they were working to solve something, they wouldn’t be able to think of alternative solutions. It’s exciting.

Is there anything else that you’d like to say about medicine?

Tenley Albright: I’d like to talk about the range in medicine. If you’ve ever thought about medicine as an interest to pursue for the rest of your life, I’d like to encourage you. Perhaps this is just my own point of view, but I can’t imagine any other field that has as many different areas within it. Right now, of course, there are tremendous, tremendous biotechnology advances. There are advances over when I went to medical school of the micro amounts of substances in the system that can be measured. I’m thinking of magnifying something 50,000 times, thinking of splicing a gene. There are so many areas. We all think of the satisfaction of being able to help another human being in a large way, or a small way, in dealing with family problems, in healing a wound, or recovering from an illness, that’s a tremendous satisfaction. But there are so many different areas.

If you think you are interested in what makes human beings tick, or how bodies work, go ahead and explore it. What’s telling us to breathe? I am not having to tell my heart to pump right now, and the heart doesn’t get tired. It rests between beats.

We don’t have to think of things like: can you swallow standing on your head? Can you drink a glass of water when you are standing on your head? You can! Do you swallow up or swallow down?Tenley Albright: Can you swallow against gravity? You can. We don’t stop to think about the amazing parts of the human body. Or of the human mind. If anything about life interests you, if you think you are interested in medicine, go ahead and explore it. You can be in any aspect of it at all, and there are tremendous ones. That’s my own point of view, but I’m sure some of you will share it.

It is extraordinary that one should be so accomplished in two entirely different disciplines. It seems that’s less likely today than it ever was. When you look at the world today, and particularly the world as expressed through sports, do you see differences? What sorts of differences?

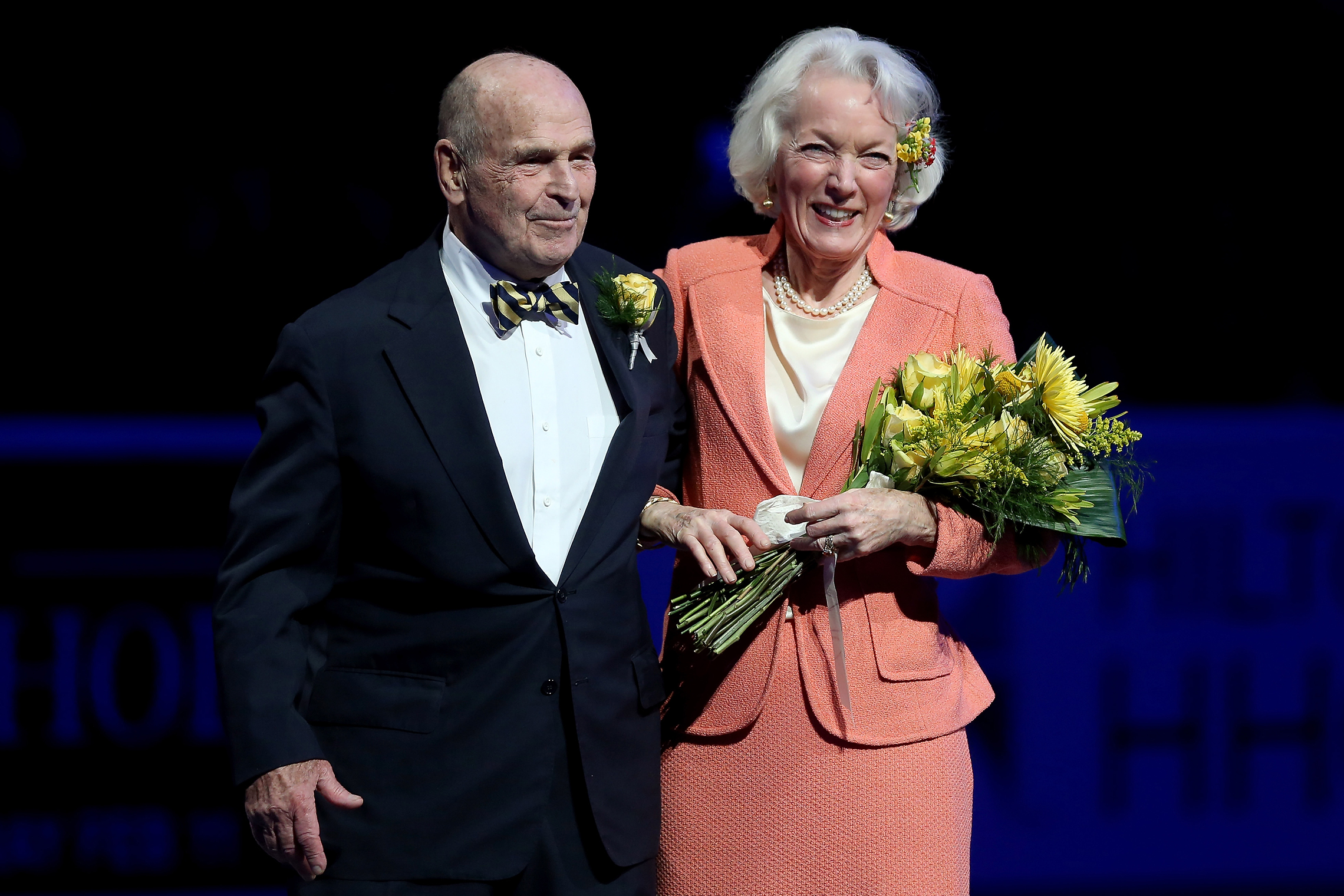

Tenley Albright: If you look at people who have had an interest, whether it is collecting insects, or whether it’s doing a sport, growing up, very often you find they don’t just stop there. They have developed a capacity to be deeply involved with something, carry it through, to try hardest at it, and to accept the challenge of doing the best they can. I think when someone has started to work on something, if they have been successful, for instance, as a top athlete it makes more sense to me that of course they would apply the same things they used in their athletics to something else. I think it’s a waste if they don’t.

There are lots of people who have been football heroes, basketball heroes, who have gone on and given of themselves. Look at Mickey King. She was the first woman diving coach at the Air Force Academy. She was very involved and encouraging the young Olympic hopefuls after she won her own gold medal. And there are all sorts of people who have done it. I wish I could remember where I read it, but I read a study of figure skating champions who went into medicine. There are a number. David Jenkins, who was Olympic champion, is a gastroenterologist. Mischa Petkevich, who was our national champion, went on to be a Rhodes scholar. I do think that what you learn from applying yourself to a sport, and really applying yourself, will hold in good stead for whatever you do. So go ahead and have fun with your sport. Don’t worry about whether you have decided exactly what you want to do for your so-called career.

It seems that there are fewer people in this decade, accomplished in sports, who choose to pursue excellence in other areas as well. Is this an illusion?

Tenley Albright: I don’t think we’ve followed people long enough yet to see if the ones in the last five or ten years who have succeeded and excelled in their sport are going to apply that to their next career. We should follow them; we should watch them. I think they will. After all, do we know how many of the musical hits right now are going to last twenty years? Not quite. I bet if we keep track, we will find that the athletes in the Olympics, these winter games coming up this year, in world championships in every sport—Tae Kwon Do to table tennis, to every sport we can think of—will take what they have learned through their sport and apply it some way. Even if it’s applying it to how they compete with each other in business or anything else they do. It’s a tough thing.

We are told that we should get in there and compete, and try to beat our competitors, and that’s a very tough thing to deal with. After all, very often they are our friends. Why do we want to beat them? That’s not the point. If you look back and think of any race you’ve been in, or anything else, stop and think. Were you trying to beat that other runner only, or were you really trying to see what you could do, and beat your own time and see how good you were and perhaps using other runners to measure yourself?

I think that’s the way it is, and that’s the way I had to look at it, because it was against my philosophy to get out on the ice to see if I could beat anybody. In fact, I remember clearly one time when we were in competition, when I didn’t really feel I had skated my personal best. It is an awful feeling, and I realized at that time that what I needed was to feel that I had prepared as well as I could for the competition. Although I never felt totally prepared, even five seconds before it, I always felt I should do more until I actually got out on the ice of that competition. But for me, it was seeing what I could do compared to what I had done, or what I had in my mind that I should be able to do. That’s what counted for me.

Your daughters skated but did not compete. It must have required some thought as to how to handle that with your daughters, your having excelled to such a degree. Did that require some attention, or was it just a natural part of the family?

Tenley Albright: I have three daughters. They still come and skate on the outdoor ponds with me. I found that putting skates on them when they were really little slowed them down. If I was over at the rink and they were on the ice too, it made it an awful lot easier to keep track of them. They all had fun with it. One of them in particular. They all took part in a few of the little competitions, or the ice shows, when they could put on all sorts of make-up and step in the ice shows with their friends when they were really little.

One of them went on to compete in local competitions, and is on her 8th or gold figure skating test. It’s been fun for me to see that they enjoyed skating, but I don’t think that it should be a need from us that our children do the same sport. One of them happens to be good in many sports, and I sometimes think, “Oh, they come too easily to her. They were never all that easy for me.” But each individual finds his or her own different path and, as a mother, I feel it’s for me to encourage whatever that path is and, lots of times, it’s been interesting to me when it’s something I couldn’t do.

Could you tell us something about your cancer research?

Tenley Albright: I’ve been very motivated during my years in surgery to find some way so that after I have operated on a patient for cancer, I could say “I know I’ve removed all the cancer.” Or else, be honest with them and be able to say “I know that there is some left, even if we can’t see it, therefore you should have a certain kind of treatment.” There hasn’t been a clear scientific way to know that. And I was very excited when I first heard Eric Fossel, who was trained in chemistry and biochemistry and biophysics, present his work on detecting the presence of malignancy simply by looking at blood plasma. And I starting working with him, began to think immediately, when I heard him speak, of the clinical applications, and the things that it could help if we could say yes, there is cancer, or no, there isn’t. If someone comes with symptoms, or tumors or lumps, and you can say, now what do we do? Does this healthy, feeling person have to be put through all sorts of invasive studies, or can we treat them another way? Now, for the first time, it is possible. I hesitate when I say this, because it is on an investigational basis right now, but we can look at the plasma and directly measure a change that normally happens in the body when the body fights the presence of any cancer cells by itself. Seeing the needs of patients in my own practice of surgery has motivated me to work on getting that clinically applied.

And in the same area, this same technology has taken me into the cardiology area, looking at the fractions of cholesterol, the LDL, HDL, the LDL chylomicrons, and measuring them directly. So, interestingly enough, I became involved with some of the technology that we didn’t have when I was in medical school, and did research with my own professor of physiology who taught me when I was in medical school, and with the professor of medicine who taught me when I was in medical school. I’ve been involved in basic research working on some similar things, and connecting with them once again, as we work to help make this available to physicians. And it’s one more example of the number of areas there are within medicine and the number of things that you may end up doing that you never thought you would.

But the interest that you have, and the things that you work hard on as a teenager can take you in to all sorts of different directions. And when you are interested in things, and you want to find out about them, and you have the curiosity, and you are motivated to make a difference, you can. And who knows where it will take you? It’s been exciting for me to find where my interests take me and are still taking me.

Extraordinary. I’m very glad you said that. Any final thoughts?

Tenley Albright: It’s been astounding to see, at the American Academy of Achievement, the opportunities that are created. When you stop and think of the greats who are honored at these things, the Nobel Prize winners meeting each other, the people in different fields, the musicians meeting people in the fields of science, the artists, the historians, the poets, it’s wonderful to see all these people coming together and having a chance to talk about common threads. And there are a lot of them. A lot of them have to do with visions and dreams and daring to dream. And again and again we keep on seeing there isn’t one person in the whole Academy of Achievement who has ever escaped hard knocks, failures. No one likes to call them failures, maybe they say there are things that don’t go quite the way they expected. But that’s what makes the stories. And every one of us has them. Every one of you with your dreams can expect to have the highs and the lows.

Figure skating is a very good example. When you “wipe out,” when you go flat on your face sliding across the ice, there is only one thing to do, and that is get up and try it again. And wow! When you’ve been flat on your face sliding across the ice, it feels so good when you finally get to the point where you can perfect that thing, and land that jump, and not be flat on the ice. And I guess it’s a much better feeling because you know what it’s like the other way. And anyone who has won anything knows what it’s like not to win. And I remember the day when I kept on hearing “Well, someone has to lose.” And it occurred to me someone has to win too. So you might as well give it a good hard try.

You certainly did. Thank you for talking with us.

You’re welcome.