Every person on this earth has a great story to tell.

Thomas Kennerly Wolfe, Jr. was born and raised in Richmond, Virginia. His family had deep roots in the region, and though they were far from wealthy, placed a high value on education. His father was an agricultural scientist, and his mother was in her first year of medical school when she dropped out to have her first child.

As a boy, Tom Wolfe was an avid reader, and early in life he formed an ambition to become a professional writer. He has always written under the short form of his name, and is not related to the American novelist Thomas Wolfe, who died in 1938. Tom Wolfe graduated from Washington and Lee University in 1951 and earned a Ph.D. in American studies at Yale University. His doctorate was granted in 1957; by then, he was already working as a general assignment reporter at the Springfield Union newspaper in Springfield, Massachusetts.

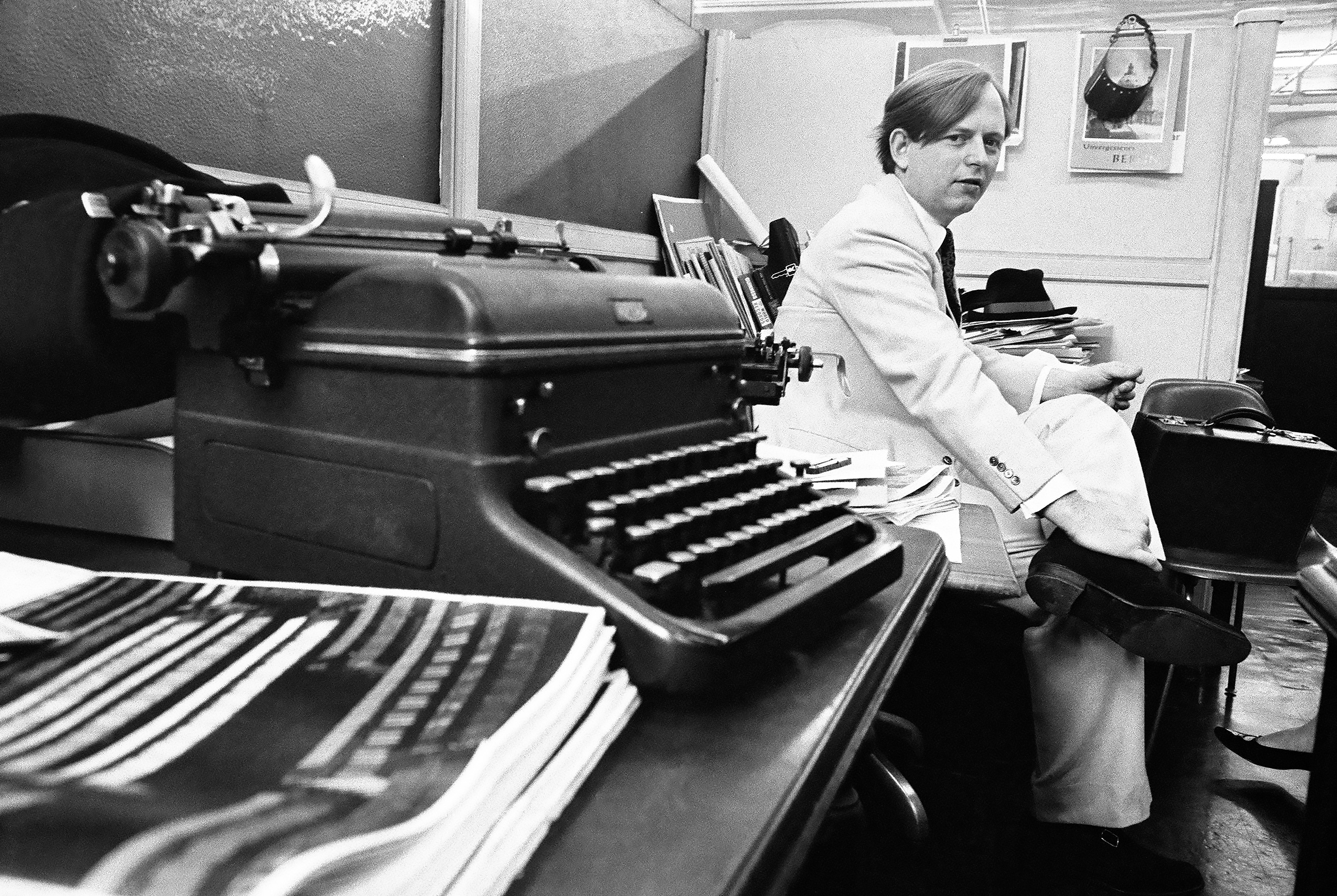

By 1960 Wolfe was a Latin American correspondent for the Washington Post. He earned the Newspaper Guild’s foreign news prize for his coverage of the Cuban revolution. In 1962, Wolfe signed on with the New York Herald Tribune. With reporter Jimmy Breslin, he was one of two staff writers assigned to the paper’s Sunday supplement, which later became New York magazine.

During the New York newspaper strike of 1962-63, Wolfe proposed an article on the Southern California hot rod and custom car culture to the editors of Esquire magazine. When he found himself stumped for an angle, his editor suggested he send him his notes as a starting point for discussion. Wolfe replied with a long, spontaneous letter, dispensing with traditional journalistic conventions and describing the whole scene in a vivid, personal voice. The editor deleted the salutation and ran the rest of the letter verbatim. The essay was one of the first examples of what came to be known as “New Journalism.” Wolfe had invented a distinctive exclamatory style, replete with pitch-perfect mimicry, rhythmic repetitions and transcribed sound effects to capture the manic energy and day-glo pop art colors of the era. In “The Last American Hero,” a 1964 Esquire article on stock car racing driver Junior Johnson, Wolfe introduced the term “good ol’ boy” for the first time to the general public outside the South. It was the first of many catchphrases that Wolfe would either popularize or coin outright.

These and other essays were collected in the book The Kandy-Kolored Tangerine Flake Streamline Baby, which became an instant bestseller. Wolfe was now the most talked-about young journalist in America, and his time as a daily newspaper reporter was over. He traveled the country, recording the dramatic changes in lifestyle taking place in America in the 1960s; his essays appeared regularly in Esquire, New York and Harper’s. In 1968, two new Tom Wolfe books were published on a single day. The Pump House Gang was a new collection of essays, while The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test was a novelistic account of the counterculture, centering on a coast-to-coast bus trip with author Ken Kesey and his band of psychedelic adventurers known as the Merry Pranksters.

Wolfe’s 1970 book, Radical Chic & Mau-Mauing the Flak Catchers, provoked controversy with its ridicule of politics-as-fashion among the New York celebrity set, and its portrayal of street-wise hustlers manipulating government anti-poverty programs. By now, Wolfe was becoming a celebrity himself; his trademark white suit made him one of the most recognizable figures on the literary scene. He continued to provoke the assumptions of fashionable elites with The Painted Word (1975), a challenge to the critical assumptions of the modern art world.

The following year saw the publication of another collection of essays, Mauve Gloves and Madmen, Clutter & Vine, which included a celebrated essay, “The Me Decade and the Third Great Awakening.” Wolfe’s coinage, “the Me decade,” was soon transformed into “the Me generation” in popular parlance.

For six years, Wolfe researched a book on the beginnings of the American space program and the subculture of military test pilots that preceded it. The Right Stuff, published in 1979, was a sensation. It returned test pilot extraordinaire Chuck Yeager from obscurity to national prominence and contributed a new set of phrases to the popular vocabulary, including “pushing the envelope” and the book’s title itself.

For years, Wolfe had made satirical drawings to illustrate his work; a selection of these appeared in his first book as “Metropolitan Sketchbook.” Since 1977, he had drawn a monthly illustrated feature in Harper’s magazine. The drawings were collected in a 1980 book, In Our Time.

The Right Stuff had brought Wolfe a whole new audience, but he was not done ruffling the feathers of the critical establishment. From Bauhaus to Our House (1981) was a full frontal assault on the critical orthodoxy of modern architecture. Having had his say on critical fashions in art and architecture, Wolfe called the literary world to account for its absorption in formal experimentation and the minutiae of undramatic lives, and for its relative neglect of the larger society’s public dramas.

Wolfe had long dreamed of writing a big novel of contemporary life; he now set out to do so in the most public way possible. Like the great novelists of the 19th century, he would publish his work in serial form, one chapter at a time as he wrote them. Throughout 1984 and 1985, a new chapter of Wolfe’s tale appeared in Rolling Stone magazine every two weeks. Although his critics conceded that the individual chapters were entertaining, they insisted that a work written in this fashion would never hold together when assembled between hard covers. Wolfe gave himself time to prepare the work for publication.

When The Bonfire of the Vanities finally appeared in book form in 1987, it was his greatest success to date. It remained on the New York Times bestseller list for over a year, and sold millions of copies. Its portrayal of New York’s “money culture” of the 1980s has made it a touchstone of the era. Wolfe was paid a record-setting $5 million for the movie rights.

Wolfe’s next novel, A Man in Full (1998), was a hugely ambitious panorama of American life at the turn of the 21st century. It outsold even The Bonfire of the Vanities in hardcover. A collection of essays and short fiction, Hooking Up, appeared in 2000, and included the novella “Ambush at Fort Bragg,” previously serialized in Rolling Stone.

Tom Wolfe’s third novel, I Am Charlotte Simmons, was published in 2004. In his 70s at the time, Wolfe set himself the difficult task of anatomizing the sexual mores of American college students. The result was simultaneously sobering and hilarious. In his last book, The Kingdom of Speech (2016), Wolfe challenged a prominent school of linguistic theory and proposed that the faculty of speech, rather than natural selection, has been the driving force of human development. In 2017, it was announced that Leonardo DiCaprio plans to produce a dramatic miniseries based on Wolfe’s The Right Stuff for the National Geographic channel. Tom Wolfe died in Manhattan at the age of 88.

Tom Wolfe was already a bestselling author of nonfiction when he took modern American novelists to task in print for failing to mine the riches of the life around them. His critics claimed that the kind of social novel he proposed in his essay, “Stalking the Billion-Footed Beast,” was no longer possible, but Wolfe proved them wrong with his own first work of fiction, The Bonfire of the Vanities. A runaway bestseller, it is now recognized as the classic literary account of New York City in the boom years of the 1980s.

The foremost pioneer of the New Journalism, Wolfe revolutionized American writing in the 1960s, documenting the emerging counterculture in books and essays such as The Kandy-Kolored Tangerine Flake Streamline Baby and The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test. At the end of the ’70s, he staked new ground with his provocative critiques of modern art and architecture: The Painted Word and From Bauhaus to Our House. In The Right Stuff, he brought to life the untold story of America’s first astronauts and made a national hero of test pilot Chuck Yeager.

Wolfe continued to document the ever-changing manners and mores of American society in his novels, including the bestseller A Man in Full and I Am Charlotte Simmons, an exploration of contemporary university life. Readers snapped his books off the shelves, and critics hailed him as a unique literary stylist and the premier chronicler of postmodern America.

In your career, you’ve written fiction that’s very realistic, and nonfiction that employs some of the tools of fiction. How did you come to these hybrid forms?

Tom Wolfe: When I was in college, like almost everybody who was serious about writing and thought they might themselves be writers, I thought that writing was 95 percent genius. You had to write about something, so the other five percent was just this clay that you fooled around with. That’s why I think there are so many terrific young poets, because poetry is the music of literature. Just playing with words can do just marvelous things, when it’s used as music. But then you reach a certain age and you realize that the ballgame, in terms of prestige in literature, is not poetry, it’s prose. Whether that’s good or bad, that’s the way things are. And at that point, you find the young writer cannibalizing his life — let’s say he’s 22, 23, 25 — and he writes his first novel. And it may be great too. Everybody’s life has great material. In fact, Emerson said, “Every person on this earth has a great story to tell, if only he can figure out what is his unique experience.” But he didn’t say everyone has two. He said everyone has one. So now the second novel comes along, and that’s when you get this kind of pathetic novel. It’s about a young novelist who had a great critical success with his first book but he really didn’t make any money, and he’s living in this four-story walk-up in the Clinton area of New York, and he doesn’t have a girlfriend, can’t go out to dinner. And this is not really a terrific novel. Nobody really cares about his fate after his great critical success.

The writing programs, where you get the Masters of Fine Art in writing, are always telling people to “write what you know.” And students interpret that to mean your own life. Unless you’re Count Tolstoy, there’s not that much in your own life. I’d be out with a cup if I had to write sheerly what’s based on my own life. But in the 19th century, where there were so many great realistic novelists, they understood you had to go outside of your own life to get new material. Even Dostoevsky, we think of him being such an internal, psychological creative force. When he wanted to write about the student radicals of his era, he went to the archives. And then started going — he’d hear about a meeting of some of these groups, he’d go attend, to just get the material. Dickens was, of course, famous for this. Zola did it just time after time after time, going to a new area of life. He wanted to get all of France into a series of novels, and he pretty well did. He’d go from farming to warfare, to whatever he thought he really hadn’t covered yet.

You yourself didn’t start out writing fiction, but journalism.

Tom Wolfe: I became involved in what eventually was known as “The New Journalism” as soon as I got to New York. I still had in my mind I was going to write a novel. But this New Journalism — which was writing nonfiction using devices of the novel and still being accurate in the journalistic sense — was so exciting; you know, people like Jimmy Breslin and Gay Talese, who were doing it, and many others —that I just wasn’t interested particularly in the novel, until after I’d done The Right Stuff, which was nonfiction, and I had written it like a novel. It was the first time in my life I ever had a little cushion of money. And I decided this was a good time— if I ever was to sit down and write a novel, this was the time to do it because I could afford it. Because always, in the back of your mind, those people are saying, “Boy, this nonfiction stuff is the most elaborate writer’s block I’ve ever heard of.” You don’t tackle the big one because you’ve discovered this new thing that’s supposedly better.

So it was at that point that I started The Bonfire of the Vanities. And at first it was going to be a novel about New York. It had no real focus. It was going to be based more or less on Thackeray’s Vanity Fair. Hence the title, The Bonfire of the Vanities. And I thought I could – I had been a reporter for all those years here in New York, and I thought I could just draw upon my experiences, the things I’d seen, and write this book. And I found I couldn’t. For the way I wanted to write a novel, I had to go out and do reporting just like the reporting that I did for The Right Stuff, for The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, or anything else that I had written.

I decided I should have a great party scene — a party of great social wattage in a Fifth Avenue apartment — in this book. And I had been to a number of parties like that. And so I said, “At last. I don’t have to do any research for this.” So I wrote this chapter, and then I read it over, and it was like a gossip column. You know, just “Who’s that person? Who’s that person? What did he say? What did she say?” So the next one I went to, I just shut up. I was just on the receiving end of whatever was going on. And for the first time, I noticed the strained, willfully raucous laughter that goes on at parties like that. People laugh in this frantic manner as if to say, “See! I’m a part of all this, and I know what’s funny, and I’m just having the time of my life because I fit in!” And then I’d notice that the worst fate in the world was not to be in a conversational cluster. And if somebody’s left out, you’d see them studying paintings as if they were very fascinated with art. They’d talk to empty spots on the wall. At last resort, they’ll go up to a wife or a husband and start conversation. But you’ve already lost the game if you’re reduced to doing that. There were so many things that I saw once I was not a participant. I was just there. I noticed that, at that time — and we’re talking about the 1980s — in an apartment of great social wattage, there was never modern lighting. There were no downlighters, which is essentially industrial lighting. It was always some time in the 19th century. Everything’s overstuffed. There are these sort of small amber lamps that make everybody’s complexion look pretty good. And I just never would have noticed any of this from my own experience. And I discovered that if my radar isn’t on, if I haven’t switched it on, I don’t notice any more than anybody else does.

You have to come outside it to really observe it.

Tom Wolfe: I think you have to listen hard, even if you can’t take notes at the moment. And this is just to write fiction!

What do you think of as the American Dream? A New York Times reviewer attributed to you a sense of wonder about the American Dream, as evidenced by some of the people you write about in Hooking Up. Do you still have a kind of romanticism about that?

Tom Wolfe: I think The American Dream is very much alive. That’s why there’s incredible immigration to this country. And the idea is that no matter where you start out, you have the freedom to reach the height that your ability will enable you to do that. And the New York Times has just run a long series about class in America. They don’t even realize they’re not talking about class, they’re talking about status. I mean, when they have an article — one of the articles was about some evangelical Christians who somehow have come into money, and they know enough to go to Ivy League colleges, and they’re making inroads at Brown and so forth and so on. That’s class? These people have moved up? That is just sheer status. They’ve improved their status through hard work. And the entire series. Class, to have real class, it was understood in Marx’s day, you almost have to have a land-based economy. People have to be pretty static. And there has to be symbolism. There has to be a sense that in one class you cannot wear — in a lower class you cannot wear what they wear in a higher class. There’s a certain kind of obeisance you have to make to people who are above you. And all that is gone in this country.

You’ll notice that during the ’60s, when there were all the student protests, everything was against the middle class. I never heard a single outcry against the upper class, because there really isn’t any upper class in the European sense. Today, for example, it’s true that if you went to Harvard or Yale yourself, your children have a better chance than the children of somebody who didn’t come out of that background. But it’s far from being a class thing, because even if the family has been three generations at Harvard, let’s say — you really don’t find much of that — you’re not automatically in. They still have to reach a certain threshold in SATs and all the rest of it.

Where are the Astors today? Where are the Vanderbilts? What are they running? The Rockefellers have lasted pretty long. I think they still have a senator. But these families are more like the Chinese rule of “rags to riches to rags” in three generations. There just are not dynasties in this country, except for dynasties like an Enron dynasty that last about seven years.