How do you make sense of all of this afterward? Does it create a sense of confidence that you got through it, that you’ve been saved by your comrade?

Thomas Norris: Absolutely. I wouldn’t be here if it wasn’t for Mike.

Michael Thornton: He went through three years of rehabilitation.

Thomas Norris: You have to understand that we had a job to do, which we’d been trained very well to do. It was an unusual job, an unconventional job, a highly dangerous job, but you ran your missions because that’s what you were sent there to do. And you never thought about, “Gosh, I almost didn’t make it back from this one,” or “Boy, I was successful on that one,” or “We got ambushed on this one and we almost didn’t make it out,” you know, “Am I going to make it on the next one? Are my people going to make it back?” You don’t think about those things. Each mission is an objective that you set out to accomplish and go after. Then you forget about that and you go on to the next one. How did this affect me? If you’re asking me how did this affect me after the fact once I was wounded, obviously it changed my whole lifestyle and existence. I wanted to be a — I mean, I no longer could stay in the Navy. I went into the hospital. I spent from 1972 to 1975 in surgeries. And after that until 1978 in minor surgeries, so I was going back and forth for repair work. The Navy retired me as a result of that, and wouldn’t let me stay with the unit. So that part of my life totally changed. I was now — I mean — I had the injuries that I had to deal with. But some people look at you and say, “How did you make it through that?” And I think the reason I made it through was because of the type of training that I had way back when we went through basic DDT SEAL training. I mean there’s an ingrown desire and determination that you’re not going to quit no matter what. And the doctors even came in and said, “We didn’t think we were ever going to save you.” He said, “I don’t know how you made it — stayed alive and made it through but —” he said, “You just wouldn’t give up.”

I think that’s part of what it was. You just have a determination not to give up. And my injury — when you see the death and destruction to other people that you see in war — I mean what I have is nothing. So I lost an eye and part of my head and brain and had some other bodily injuries. But what is that? I mean, I have another eye. You just go on. You go on with what you’ve got left and make the best of it.

Michael Thornton: Just be happy with life itself, period. I mean, I live every day to the fullest, you know. That’s what I tried to tell these young kids out here, you know. Yeah, set your goals out there but make them reachable, because, you know, every day every situation changes, and that’s in everyday life. That’s not just in the war, you know.

I’ll always have the memories of guys I lost over there. And I’ve lost friends since the war, but I’ll always have the memories. The riches are great, but riches aren’t everything, because when you go you can only take your memories and your word and your honor to the grave with you.

Tom, you not only recovered from your injuries, but you embarked on another career. Would you tell us how you made this transition in your life?

Thomas Norris: As a result of my injuries I was in the hospital for quite a long period of time. I was operated on for minor surgeries from 1972 through 1975, when I was retired from the military as a result of my injuries. And then I was in for minor surgery through 1978. So my life during that time was pretty much controlled by hospitalization and when I needed to be there for medical treatment. My spirits were very positive. I mean, you know, I was alive! It’s just another offset in my physical stature, but you just learn to live with what you have. I mean, I had a very serious injury as Mike explained. A good portion of my head was blown away, which I had to deal with, and which would restrict me from doing some of the things that I would normally otherwise be able to do. But in the whole realm of things, when you look at the injury I received, compared to injuries I’d seen while you were overseas where you see devastation and people torn to pieces — I mean, my injury was insignificant. I mean, it’s just something that happened. Now that it happened, you know, let’s make the best of it and get on with your life. So that’s kind of the way I viewed it.

Because of the medical treatment that I was receiving, I was restricted from becoming involved in any other type of activity. At the time it wasn’t like I could go looking for a job. When that time came, I knew what I wanted to do. When I was in college my studies were towards criminology, and that’s the field I wanted to be in.

I wanted to be an FBI agent, so I started pursuing that avenue. I had a very good friend who was an ex-Navy SEAL who had since been in the FBI. I contacted him. I went over and interviewed with him, as well as a number of people — agents in the office. And the outcome of all of that was we did quite a bit of research to determine whether or not there was any other people in the FBI who had injuries similar to mine. And there had been an agent who had lost his eye while he was on active duty, but that was the only incident we could find. And I no longer — obviously I did not meet the physical requirements to become an agent. So we decided pretty much in order that if I was going to become accepted at all I would need to have a waiver through the Director of the FBI. So I wrote him a letter requesting that he waiver my disabilities. And it was Judge Webster, William Webster was the Director of the FBI at that time. And surprisingly, he wrote back and said, “If you can pass the same test as anybody else applying for this organization, I will waiver your disabilities.”

I also had to get an age waiver since I was already over the maximum age to be hired as an agent by the Bureau. Once that happened, I was on a fast track to take the examinations, have them graded and approved, take the physical testing, and the agent interview, and get in the chain of eligible agents to be selected. Even though you’ve passed all the tests, the Bureau selects its people depending on how many people pass the test and are waiting for a class.

What year was this?

Thomas Norris: 1979. I did very, very well. So I was brought in to the Bureau. As a matter of fact, I asked for a little delay because I needed a little time to adjust. I was brought in as an agent in September of 1979.

Returning for a moment to Michael Thornton, did you stay in Vietnam after the incident we discussed or did you come straight home?

Michael Thornton: No, I stayed over there for a while. I was at home in March of 1973 and it was Woody Woodruff — the guy that was on the extraction and insertion boat for Tommy who came and knocked on my door. He said, “I don’t know if you’ve heard or not. You’ve been submitted for the Congressional Medal of Honor.”

I was already home with my wife and my two children. I didn’t believe it. But the next thing I knew I got a letter — a message to SEAL Team ONE — that, “You will receive the Congressional Medal of Honor. Your name is being carried through all these different boards…” Because it goes through several boards, and it goes to the Joint Chiefs of Staff. It’s the one medal that all the Joint Chiefs have to say thumbs up on. After it goes through the Joint Chiefs, it goes to the Senate, but after the Joint Chiefs give their blessing, the Senate and the Congress and the President are just a formality.

When were you actually awarded the Medal of Honor?

Michael Thornton: I was actually awarded the Medal on October the 15th, 1973, and Tommy was still going through operations in Bethesda, Maryland, at the time. And they weren’t going to let him out because he was getting ready for another operation, and they were looking all over the place for Tommy and he was staying with me at the hotel in a room, and everybody in the world is trying — and then we had to try to get him the clearance to get into the White House. Well it was really funny. We got him clearance to get in the White House — for everybody to go to the White House. It’s kind of like when I came here — everybody was cleared to go in the White House but me. I was not cleared to go in the White House. It was really funny because the same thing happened — I didn’t have my credentials or something when we went over to the — and I said, “Well, give the medal to Tommy.” But I’ll never forget that day. My mom and dad was there. My brother was there. Tommy was there. And the President asked me, he said, “Mike, you know, what does this mean to you?” It was President Nixon, and we were in the East Room. And I said, “Sir, if you could take something and cut this in half, I’d like to give the other half of this medal to the gentleman who is standing behind me,” and that was Tommy.

And after that I went back to California and I was still in SEAL Team ONE. Then I went to BUD/S — basic underwater demolitions training. I was an instructor there. Tommy used to come out and visit my family in California, and he would come to the training unit. What an inspiration to these young kids! They’ve heard the stories about this guy, and they’d see this guy with all these injuries out there running and doing these things, and he’s got half his head gone! They’ve done a lot in the way of repair and the surgeries since then, but you could really notice it back then.

At what point did you feel confident that Tom was going to have a full, rich life again?

Michael Thornton: I knew that as soon as I saw him the next time. Tommy is such a motivated person, I felt if he hadn’t died in the first week he was going to make it. Everyone I spoke to after I got back, even the doctor, said he didn’t feel that Tommy would ever make it. I called Clark Air Force Base after Tommy went there, and they told me how long the first surgery took and of course nothing looked good at that period of time. They called to bring his family over to the Philippines. When they do something like that, that’s usually the last straw, but he’s sitting here now.

This guy right here gave me a lot of fortitude and courage because what of I saw him go through. Just the rehabilitation. It’s unbelievable what Tommy went through, and people just don’t understand it until you stand back and watch what he had to deal with in his life.

He had other injuries which I’m not going to talk about but he knows what I’m talking about. There’s always difficulties and he always overcame them and never asked for anything. I used to get so angry. He’d be sick and he wouldn’t call me and then when I’d find out I’d be so mad I couldn’t see straight.

What difference did the Medal of Honor make in your life? Did it change the way you thought about life?

Michael Thornton: It wasn’t the medal. It was being in Vietnam itself. The close situations changed my whole way of thinking about my life. It showed me that things can disappear like the snap of your fingers. As a young guy you thought you were invincible and nothing could ever hurt you, and stuff like that, and living life to the fullest. But making goals, reachable goals. I speak about goals that I reach but not to worry too much about what’s ahead, but just take care of what you can control today, and what you can take care of today, and then moving from today to tomorrow. When you wake up and everybody says, “How do you feel, Mike?” I say, “I’m alive.” As long as I’m alive I can deal with anything that’s out there.

We’d like to start by recalling what each of you were like growing up. Mr. Thornton, at age ten, where are you living, what are your family circumstances?

Michael Thornton: I’m living in a very small town north of Spartanburg, South Carolina, growing up in the woods, about 560 acres. My brother and I are playing cowboys and Indians in the woods and my mother has a bell that rings us to come to dinner. There’s no TV, so you were just outside all day enjoying nature and life itself.

I went to Spartanburg high school, and when I graduated I had been suspended more than anyone in the history of the high school. My father believed in having a good time but he believed in rules and regulations and discipline, too. He disciplined me. I know one time I was playing basketball and we were supposed to be playing for the county championship and the coach wouldn’t let me play. They had the whole team out there and he said, “That’s it.” My father knew that was important to me, but he knew what was more important was going to school and getting an education. And he believed you never talked back to your mother. You showed her respect at all times. You always showed respect to your elders and especially your mother and father. If my brother and I got in a scrap he’d let that work itself out. But we learned you protect your little sister at all times.

Mr. Norris, take me back to your ten-year-old self. Where are you?

Thomas Norris: Ten years old, my family had just moved to Silver Spring, Maryland, from Wisconsin. I have two brothers and my mother and father. Like any ten-year-old kid, I was going to school and involved in the normal activities that ten year-old boys are.

Are you in the country? Are you in the city?

Thomas Norris: We are in the rural suburbs, I guess you would say, which was a little bit of change from Wisconsin. My dad was in the military. My mother and father were both school teachers. When World War II broke out my father went into the military and after the war he went to work for the Veterans Administration. I think the country at the time was much more patriotic, much more involved in world events and the love of God and country. Just like Mike, discipline was a major factor in growing up. There was a lot more respect for adults, for your elders. I think you learned a lot more responsibility then.

Did any movies influence your thinking when you were growing up?

Michael Thornton: I know the first movie I ever saw was Old Yeller and I remember crying. At that age that you cry at Old Yeller. John Wayne was someone I saw a lot. My father could never swim and when we were young he made sure we went to swimming lessons at the Y. Back then they had state swimming pools and we swam on the swim teams, because he could never swim and he wanted to make sure his boys could swim.

I saw the movie The Sullivan Brothers about the five brothers who died during World War II, and those family values that my dad had always said, “Your family,” you know, “were to die for,” you know, basically. And I saw how those five brothers died trying to save the one. And that was a big influence, so I said, “Well, I’m going to join the Navy,” when I saw that movie. Then I saw the movie The Frogmen with Richard Widmark. I said, “Well, I’m a good swimmer. I want to be a Navy frogman.” Because I loved the excitement. I loved what they were doing and stuff like that. And when I did finally get out of high school — because when I got out of high school, you were only allowed to miss 30 days and I missed 78 days, and they still graduated me. So I didn’t think they wanted me back.

Vietnam was hot and heavy. This is around 1967 and the draft was big and I had already been selected 1A so I knew I was going, but I wanted to be a Navy frogman, and if you got drafted you went straight into the Army. I wasn’t worried about going to Vietnam. That didn’t bother me one way or the other. Actually I wanted to go. I knew my father was in World War II. He joined the service in ’36 and got out in ’46 after the war. My dad taught me this is the greatest country in the world and he had been able to travel during his time in the military. I’ll not say I was ignorant about Vietnam because every country I’ve ever traveled to, I’ve always tried to read about it, learn about where they come from, their religion.

My father said, “You need to understand the people.” My father lived in the Philippines for four years and he said, “You need to understand the people and their religion and their way of life. I’m not saying it’s good, bad or indifferent, but that’s their way and you’re going into their country, and you need to try to understand it to be able to communicate.” Tommy and I both, being in the SEAL team in Vietnam, I lived with the people almost all the time. I didn’t live on an American base. I came very close to the people.

How did you become a SEAL? What was the process?

Michael Thornton: I wanted to be a Navy frogman; back then it was called “underwater demolition recruit training.” I joined the Navy and went to boot camp. After boot camp back then you had to go to a ship before going into the training. I went aboard a ship for just a very few months. The ship was decommissioned and I started training in Coronado, California. We started off with 129 students in my class. We actually graduated with 16 but four of them were injured and they were rolled back to the next class.

Did you know what the odds were of making it through? Did they tell you only some of you are going to make it?

Michael Thornton: Oh, yeah. They were constantly saying, “You’re worthless. You’re not worthy of being here. You’re dirt.” Your shoes are so spit shined you can see your face in the thing, and this guy walks up and takes his boot and rubs it across saying, “You call that a shine job?” All you do is turn around and jump in the water and say, “What am I going through this for?”

What were you going through it for?

Michael Thornton: Because my father taught me to never give up. I was there for a reason. It’s something I wanted. I wanted to be successful and I had set my goal. I was going to make it through this training no matter what. I had been on a ship for just a couple of months. I knew what a ship was like. Every time I’d do an about face and those ships across there in the bay I’d say, “I don’t want to go back there.” It was kind of like Jim Stockdale not wanting to go back to the Hanoi Hilton. You’ve been there, don’t want to do that again. They said, “You can’t do it,” and I’m telling myself, “I can do it.” Everything was different back then than it is to now. Everybody says, “Was training harder back then?” They used to hang us from pull-up bars and use us for punching bags!

Mr. Norris, you came to the SEALs through a different route, didn’t you?

Thomas Norris: I did. Mike went into the service right out of high school. I went into college. It was 1962 when I graduated from high school. A majority of the students at that time were college oriented. You know, get your college degree and go on to whatever career you had chosen. I’d work three jobs during the summers. I’d go from one job to another job and the next job. I’d work 12 to 16 hours a day to earn enough money to go to school. I had a scholarship as well, but my value system was to achieve your goals. Set one and go for it, and that’s what I was doing.

I graduated from college. I wanted to go to law school. Unfortunately, like Mike said, the draft was a major factor back. Draft boards had the option to exempt where they wanted to. They could cut off when they wanted to. As a student you were exempt from the draft. Once you graduated from college, they exempted medical students, but I was caught up with the draft, so going to law school wasn’t an option. The Vietnam war was going then. It’s 1967, I guess. We were heavily engaged in it. There was more troop involvement, so the draft was a major factor. It interrupted my career path. It wasn’t that I didn’t want to go in the service. I very much believed in serving my country, so that really wasn’t a factor. I would have liked to complete my education and then gone in the service but I didn’t have a choice.

Mike Thornton had decided in advance that he was going into the Navy. Were you going to let the draft board decide for you?

Thomas Norris: No. I had set my goal. If I had to go in, I wanted to fly airplanes, and I wanted to fly for the Navy. I wanted to fly off the carriers. I thought that was the neatest thing going. I had never even been in an airplane but I used to go out to the airport to watch the planes come in and take off. I had no opportunity to get into one but I was fascinated by airplanes and I even knew what plane I wanted to fly.

You had to take a written examination in order to become a pilot and join a flight officers program, which I passed. Then you had to take a physical examination and part of the physical examination was an eye exam. Well, I couldn’t pass the eye exam, which was very upsetting to me because I had set a goal. This is what I wanted to do and now they’re telling me, “Sorry, you’re not going to be able to do it because you can’t pass this exam.”

So I got an ophthalmologist and worked on my vision. I had problems with depth perception. Not as bad as I have now but I did have a problem with it then, and I had it corrected to the point where I could pass the eye exam with the ophthalmologist but I couldn’t pass it for the military. I went to Andrews Air Force Base, tried to pass it there, could not. I went to Quantico Marine Corps Base where their medical facility was, trying to pass it there, could not. And I went to the Naval Hospital, Bethesda, and tried to pass it there, could not.

I had a very close friend who had gone through the Navy flight program and was now an instructor. I talked to him and he said, “Tom, if you really want to do this, go in as a Naval Flight Officer, NFO.” It’s the back seater, the navigator for the program. “When you get down to Pensacola, take the eye exam. I know you’ll pass it.”

So that’s what I did. I took a chance because I wanted to fly. I did what he said. I went to Pensacola. You go into indoctrination training and you’re under the control of Marines, which is an eye opener for anybody. Marine drill instructors is a totally different experience than I’d ever before. Talk about discipline! The first thing they do is take you in for your physical examination. They lined us all up and off we went to the medical facility.

I’m standing in line behind all these other students and they’re holding up this little box that has three sticks on it and we have to tell them which one’s forward or which one’s back. I’m listening to the kids in front of me and they’re all rattling off the same thing so I sat there and I rattled off the same thing. I don’t know whether I saw it or not. But I asked the guy how I did and he gave me a thumbs up and I went a mile high! You couldn’t hurt me the rest of that day no matter what, I passed that exam. So to me that was just the greatest thing.

To make a long story short, they didn’t accept that. I had to go in for a full eye exam with a naval ophthalmologist. To this day I don’t know whether I passed that exam or not. They dilated my eyes. I had to sit there for a long time waiting for that to take effect and I was talking to this doctor. He was a lieutenant commander, I guess, and I’m just a young kid. I’m not even commissioned yet —I’m just a student. I think he took a liking to me. To this day I don’t know whether I passed that exam or not, but he passed me.

I was transferred into the pilot program and I went through a great deal of the training, but finally my depth perception caught up to me. It’s a little bit different to try and land on a runway that doesn’t move than it is to land on a carrier deck. So I was washed out of the program. I had never failed in something that I wanted to do, and I was devastated.

So I was faced with a commitment to the Navy, and I didn’t particularly want to go aboard a ship. I had read in Reader’s Digest an article about the Navy SEAL teams.

Mr. Thornton, how did you come to know about the program?

Michael Thornton: I heard about the program when I started training. I didn’t know anything about it. Everybody said, “Man, you want to be a SEAL.” I said, “No, I want to be a Navy frogman.” “No, no, you want to be a SEAL.” So you went through training and at every step you heard more and more about SEAL team. Some of the instructors like Vince Olivera had been in the SEAL team. Some of the instructors had been in the SEAL team, and these guys looked like mountains of steel.

And as I got farther into it, they’re talking. “Yeah, you still do the diving. Yeah, you still do the parachute jumping, but in the SEAL you do a lot more land operations.” And that kind of clicked. That’s more what I was brought up with, playing in the woods. They’re talking about Vietnam, the jungles, and I said, “That sounds more exciting.”

What were they looking for?

Michael Thornton: I really don’t know. I guess everybody has a little bit of leadership. I was never afraid to step out and make a decision. It might have been the wrong decision. As Tommy knows, I’m not afraid to tell somebody if I think they’re wrong, as long as I know that I’m right. I would always try to make sure that I was right and then I’d voice my opinion.

Your first eight weeks of training you go through a lot of physical — I mean, harassing, harassing, harassing, harassment. Just everybody telling you you’re worthless and you’re not this. Doing push-ups, calisthenics, running. I mean, you don’t go anywhere. You run everywhere, you know. You’re the lowest animal in the world, you know, and you’re right underneath a cockroach, you know, as far as they’re — and that’s the way they treated you.

Why did they do that? What were they trying to bring out?

Michael Thornton: They grew you to be physically strong, but they want to see how mentally strong you would be and that’s the whole thing. What type of mental pressures can you take when you are in combat getting shot at? How are you going to accept mental strain when you see your buddy shot? When you get hit yourself, how do you react and how do you focus? Well, you still focus on the inner you. You’ve got to use that fear in a positive way. You focus that fear towards the objective. The objective is to get the enemy before the enemy gets you.

Thomas Norris: What they’re looking for is the character and the drive of a person that they’re putting through training. They’ve got a lot of kids. They’ve got big kids, football players, muscular people and they’ve got little people like I am. But they’re looking for the heart and the determination and a mindset that says, “I’m not going to give up. I’m going to push beyond what I think I can do because I need to do that.” They want to see you push 110-120 percent beyond what you think you can do and they drive you to that. They can break anybody. Somewhere in training they’re probably going to pick on you and it’s going to be your day.

Training is tough for everybody always. It’s a strenuous program. It’s tough on your mind. It’s tough on your body. But what they’re looking for is those folks that aren’t going to give up, those folks that are going to keep driving. They want to instill also as part of that drive a responsibility for team membership. You never give up your team buddy. You never give up your team. You get each person through. If one of your team members quits, you do everything you can to try and ensure that he won’t, but if he does then you take up that slack and you never leave anybody behind. You’re always helping each other.

They want to see that drive. They want somebody that’s not going to give up. If you’re going to give up, it doesn’t matter how big or how strong you are. You’re no use to them. They know where you’re going. They know in combat you’re going to be outnumbered every time and they can’t have somebody there that says, “Gosh, I can’t do this.”

There was one instance where the naval personnel said, “You’re just not passing enough people. We’re putting classes through with 100 people and you’re graduating 10.” But they realized there was a reason we did what we did, in order to get the type of people that we needed for that program.

How did the two of you meet? Was it in Vietnam? What were you doing?

Michael Thornton: Tommy and I both had previous tours in Vietnam so we were combat ready. I had been in a lot of fire fights. I had already received numerous awards, you know. I had heard of Tommy but I personally didn’t meet Tommy until the first time that we met in Vietnam. I think it was in Da Nang.

Thomas Norris: Yeah, it was in Da Nang. In ’72, I think. I learned about Mike very quickly. If you’re a member of the team, your capabilities are automatically substantiated.

How did you come to work together in Vietnam?

Thomas Norris: You have to understand where Vietnam was at that time. Each president had a different idea of how the Vietnam War would be run. Under Nixon we were in a mode called Vietnamization, which meant the U.S. military was pulling out. We were giving command of the military to the South Vietnamese to defend the country on their own. The only reason that — the only thing — we resumed bombing runs then but it was mostly in support of their aggressive action in order for them to achieve whatever goals they were achieving. But it was limited and most of the U.S. personnel were being pulled out of Vietnam. In June the only people on land — active units — were the Navy Seals.

Michael Thornton: They still had some support areas down around Saigon and areas like that, but as of September the 6th, 1972, there was nobody left at all except for a few of us and that was it.

Thomas Norris: We still had ships to help support the South Vietnamese forces. Most of the air units had been drawn down, and they had to bring those back again because of the Easter offensive, which was a shock or surprise to the command. They brought the B52s in and they started intensive bombing raids to try and help stop that invasion. Prior to that most of those units had been dismantling and they were scrambling to try and get personnel to make those missions.

Give us an example of a SEAL team assignment. What would you be challenged to do?

Michael Thornton: Well, there’s a lot of different things. In my first tours, which were all down south in the swamps, we were trying to infiltrate and mess up their logistic plans, their infrastructure. If you could capture a province level chief, the information — the intelligence — you could gather from this guy is unbelievable. They break it up just like a state. You had a province level just like the governor, and then you have a district, and then you have a village, and then you have a hamlet. So whenever you could disrupt that chain of command it was really hard to replace. There were always disruptions, and somebody waiting around to make another decision.

A good thing that they tried to teach us in training is, “Make a decision why you’re there. Make that decision and move on.” There were a lot of operations where I’d gain intelligence and I’d take these personnel and I’d move and hit three different operations, because the intelligence was live, it was right there. I knew if we waited too long I wouldn’t be able to get to that position and that guy would be gone. So basically intelligence was everything.

Thomas Norris: The SEAL teams started out as intelligent gathering units. The only area that the Navy had responsibility for in Vietnam was the Lan Tao shipping channel. We were under the command of Admiral Zumwalt, who was kind of a radical in his own right. He later became Chief of Naval Operations. A marvelous man and a very good commander.

The only control the Navy had in Vietnam was that area and that’s where we were sent, initially to keep those shipping channels open, and we were very successful at doing that. So we expanded. We gained intelligence on other things and we’d feed it into the command system. It would go to Army units to run those missions, but they were so heavily involved in their own operations that they couldn’t handle some of the information we were giving them. So we started running our own missions.

A SEAL platoon is made up of 14 people: two officers and 12 enlisted. And then you’re divided into two seven-man squads, and you would either operate as a seven-man squad or sometimes one or two or three people would go out on missions. And we would get our intelligence from either people that “chu hoi’d” or gave up, people we captured and turned over, interrogated, and came up with information from various sources. I mean, we lived with the Vietnamese people. And then we would penetrate into areas where nobody else would go. We ran into the base areas of the Viet Cong. We went to places where big army units didn’t go. And we ran our operations. Unconventional warfare is a different type of battle. It’s not on line tanks and military units facing each other. We fought an underhanded, dirty, ruthless type of a war, and we were usually — always — outnumbered. Our main goal was intelligence, to give us information on where the VC were, where their heavy weapons units were, where their mortar positions were, where their strike positions were, where their manpower was, and then go target those positions. And that’s what we went after. We went after their main military positions and we penetrated into areas where nobody else would go.

I guess if you sat down and thought about it afterwards, you’d probably go, “Why did we do that? What are we doing here?” But when you get back from a mission — you don’t really think about it during a mission. Or you’re in a heavy fire fight and your mission is a heavily involved contact one. And when you get back you don’t really let that — you can’t concentrate on that. You can’t sit there and say, “Geez, I almost didn’t make it,” or you wouldn’t operate again. You just wipe it out of your mind and you go on. And you gather — you have almost a sixth sense when you run operations. You feel things almost before they happen. It’s hard to explain to somebody that’s never been there what it’s like to work in an area where you’re outnumbered.

Michael Thornton: Every time.

Thomas Norris: So you depend on the fellow members of your team to do what they’re supposed to do.

Michael Thornton: I mean, they’re your family. They’re everything. It’s like my father, the values. Your family is everything, and they were my family there. Good? Bad? War stinks! There’s nothing good about it. But you know the whole thing, it’s you or them. We were projecting in areas where nobody else would go, the reason why it was called “free fire zones.” And a free fire zone was a fire zone because it was controlled completely by the NVA and the Viet Cong.

That’s where they lived and that’s where they stayed because they had the freedom to move as they wanted to. They knew that they were safe. So for us to get them, we had to go after them.

I went on one operation in this place down in the very bottom of Vietnam at the very point. That whole area was divided by a river, and this is one of the areas where they didn’t use a lot of Agent Orange to defoliate for bombardment. These tunnel rats were all over the place. We knew there was a province level chief. This is like the governor. This guy was a tax collector. They had already sent a platoon of SEALS down there, and out of 21 people 19 were injured. They had to cut cables across the river to get in there.

I had captured a district level chief, and this district level chief was a logistics guy, and I captured him and I got the intel for him, and I took him, and he had the passwords to drop us. And we took a junk, and I had myself and two other guys lying down in the back of this junk, and I had what they call the KCS — Kit Carson Scouts — which were all ex-VC at one time. And these guys were up there dressed like VC on this junk with this district guy, but this district guy knew that his life was in my hands, all right, basically. So we went 11-and-a-half clicks in bad man territory just to get this guy, and my whole objective was to capture this guy but when I jumped up to grab him, he had two bodyguards, his bodyguards opened up on us. And of course you don’t want to, but you have to eliminate that thing, because good, bad or indifferent, this is the whole bad thing about war: people get hurt.

Tell us about the point where your lives really interconnected. What happened that day when you saved Tom’s life?

Michael Thornton: Well, Tom was the senior SEAL. He had two other SEAL officers, and I think we had 12 or 16 enlisted guys. Tommy broke us up in different areas, and we were working in Hoi An or Tui Nam which is way northeast, and with NVA already taking over the Cua Viet river basin, they called Tommy down and when he came back, he chose who he wanted to go back with him. We had a rotation. The ops had been taken down so low because everybody was scared to let us actually go in the areas where they saw the NVA moving. In a lot of ways, they didn’t want to do anything to upset them near the end

Thomas Norris: This was during the Easter offensive when the North Vietnamese invaded South Vietnam. My boss was Commander Shively — a wonderful fellow. He came up through enlisted ranks, became an officer, was CEO of SEAL Team ONE, which was Mike’s team. The kind of guy you’d give your life for; he was just top notch. He was military advisor to the commander of our Vietnamese Navy counterpart, the LDNN, which was the Vietnamese SEAL teams. The Vietnamese commander requested that we send a unit up to the Qua Viet Naval Base, which was in North Vietnamese hands, to determine whether or not that base could be taken back by a mission run by the LDNN, Vietnamese Navy.

The Americans wanted to know if there was any antiaircraft or missile positions being put in up there. Then Dave Shively called me down to ask me if I would take a group up there, you know, and I looked at him and he looked at me, and I said, “Dave, I can tell you what’s up there without going.” He looked at me and he says, “I know, Tom, but they’re asking if we will do it. Will you take a team?” And I said, “Okay.” I said, “Do I get to pick the team?” He said, “You can pick the team, but not the Vietnamese officer.” And I said, “Okay, fine.”

What do you look for when you pick a team?

Thomas Norris: I look for the best people I can possibly have to go into an area like that because I knew what I was getting into. I knew what was up there. I was up there running missions when this offensive started.

There was over 30,000 North Vietnamese troops up there. This is not something where you’re going to just meet a few guys. You’re going to run into bunches. So I went back to where our base camp was and I said, “Mike, put on your best gear, buddy. We’re going to war.” I said, “Pick the best two Vietnamese you can.”

Michael Thornton: I picked two Vietnamese that worked with me on previous tours down in the south. These guys were enlisted guys and they were go-getters. I had been in a lot of tough fire fights with these guys down in the jungle, so I knew we could count on these two guys. We had our Vietnamese officer, Kwan and we knew he was going to be a great guy, but he had gotten in a boating accident the day before.

Thomas Norris: Yeah, he did. So the officer that was chosen was a fellow that I had worked with on some prior training operations, and he just wasn’t as confident of his people as he should have been. We had a hard time initiating an ambush when we had the opportunity. Maybe he could have grown into it, but he just wasn’t as confident as he should have been. If I had to pick a strong leader to go on the mission I was running it would not have been him, but I didn’t have that choice.

Mike didn’t know anything about this. He knew about the two enlisted guys because he had worked with them before. He knew they were very competent. I knew Mike was the most solid guy I could have with me, and I put another very solid guy on the boat that went up with us, a guy by the name of Woody Woodruff. So we were, in essence, a five-man team.

Michael Thornton: These guys were on rotation. All these guys were go-getters. They wanted to do whatever they could do — the 16 enlisted guys. We had a lot of other guys that had been on previous tours, too. I knew what Tommy was in for; Tommy and I discussed it, but I would never say no anyway. I knew what I had been through before. If you have a chance to be there to help save somebody else’s life or vice versa, I knew the decision I had made. Tommy said, “You and I are going to go,” and I said, “Yes, sir.”

Thomas Norris: I had preplanned this operation. I preplanned fire positions for the naval gunfire if we needed assistance. This assumed that we were going into the Qua Viet Naval Base. My positions were around that base, so if I called in a fire point they would know automatically what coordinates to shoot at, and I designated the type of artillery rounds I wanted. They were going to vector us into the naval base so I wasn’t having to rely on the Vietnamese boats, junks, to get us in there. We would be radar vectored in. And we set out on our mission.

We were taken up in a Vietnamese cement junk. We were going to insert off of rubber boats once we got vectored into where we were supposed to be. Well, the problems started developing early on. We were a little late in getting started. The water slowed us up. We couldn’t make the headway we thought we could. The American vessels that were supposed to vector us were not in a position to do so when we got to the area, so we couldn’t get the radar vectors.

The boat captain assured me he could get us into where we were supposed to be so we ran on his reckoning. Unfortunately, we were north of the Qua Viet river, but he did vector us in. We got in our little rubber boats and went in as if we were going to where we should go. We didn’t know we were not where we were supposed to be until we got on the beach. But we took the rubber boats in and we got off, and swam into shore.

We went across the beach and started our patrol in the direction that we would have normally gone had we been where we were supposed to be. At night in a heavily controlled area you move very slowly. It’s not like you’re just walking into wherever you want to go. It’s very slow moving. You stop, you listen to what’s around you. You take a lot of time to become accustomed to the area and the sounds of the area and what the area is like. Mike was back at the back of the line and I was up towards the front. Mike had a starlight scope, which is a night vision ocular device. Mike would come up to me and he’d say, “Nasty…”

Michael Thornton: I called him “Nasty Norris.”

Thomas Norris: He used to try to call me “Nasty.” “Nasty,” he says, “I don’t see the Qua Viet river, which means we’re not where we’re supposed to be.” So he should have been able to pick it up on the starlight scope. And I said, “Okay, Mike.” And he’d kind of look at me, you know, like — “You nut, we’re not where we’re supposed to be.” And he’d go back to the back of the line and off we’d go and patrol some more. And you know, every time we’d stop he’d let me know that, you know, “Hey, dumb-dumb, we’re not where we’re supposed to be!”

Michael Thornton: We were seeing bunkers and bon fires going and all these guys bouncing around.

Thomas Norris: We were patrolling through heavy, heavy North Vietnamese units. There were bunker complexes like I had never seen before.

Michael Thornton: We figured we were in North Vietnam.

Thomas Norris: Yeah. It was incredible. So we’re just moving on through.

Michael Thornton: Just grabbing all the intelligence we can.

Thomas Norris: And Mike, I think he’s thinking what kind of a nut am I with here? Now I can pass for a Vietnamese because I’m small. If they don’t see my nose and my facial side views, I can pretty much get away with it. Mike being as big as he is, there is no way Mike can pass for a Vietnamese. Mike is trying to make himself as small as possible, you know, in the middle of this.

Michael Thornton: And I’m trying to keep these two young Vietnamese SEALS calmed down.

Thomas Norris: I don’t think the officer ever saw or knew exactly what it was we were going through. Either that or he was so scared he was never opening his mouth.

Michael Thornton: We had Tommy in the front and me at the rear and we had them in between us. I’d go by and one of the Vietnamese would say, “Mike, is Tommy okay?” I said, “Oh, he’s okay.” “Okay.” Because he wants to know why in the hell are we out here. We know we’re in such an area, because Tommy is talking about bunker complexes. This is something that took years to build: gun emplacements, big bonfires. All these guys walking around these bonfires.

Thomas Norris: We patrolled right through them.

Michael Thornton: Right through the middle of them.

You both were awarded the Medal of Honor, but not at the same time. Can you explain how that came about?

Thomas Norris: My action occurred in April of 1972 about six months prior to when Mike and I operated together. This action was the result of the North Vietnamese Easter offensive push into South Vietnam. The United States retaliated with B-52 strikes and during one of those strikes an Air Force electronics plane was shot down. The only survivor was the navigator, Lieutenant Colonel Ideal Hambleton. When he came up on a survival radio an effort was immediately instituted to try and rescue him. A Huey helicopter was shot down with a three-man crew. Two of them were killed and one of them was captured.

On the second day, two more helicopters went in and were so badly shot up they had to abort the mission, and a forward air controller aircraft was shot down, putting two more individuals on the ground. One was captured and one became just like Hambleton. They went in with one more rescue attempt. They were shot down and lost a six-man crew. The day after that another forward air control aircraft was shot down with two men aboard. One was killed and the second one, First Lieutenant Bruce Walker, was missing on the ground. After five days’ effort, we had 14 people killed, we had lost eight aircraft, we had two people captured, and we had three on the ground to be rescued. That’s when I became involved.

The Joint Personnel Recovery Center was following that operation. They thought a pick up could be made on the ground. I was briefed on the operation. The pilots were near a river called the Mu Gang. They thought we could float down, and we could pick them up. I had a team of five people, a Vietnamese officer and three Vietnamese soldiers and myself to attempt this rescue. We were taken to a forward base where we worked from, an old French cement bunker. There was a Vietnamese tank unit there, with three American tanks with no ammo for their main guns. And the guard force was under orders to retreat any time that they felt unsecure. So that was our protective force.

My team started out the first night. The pilots had been told by code to float down the river and they’ll be rescued. They didn’t know where or when or anything else. Only one of the pilots could make it to the river and that was First Lieutenant Mark Clark. We went through numerous North Vietnamese units, but we got to a position where we thought we would intercept Clark. About two in the morning we heard him in the water; he was breathing very heavily. But at the same time we had a North Vietnamese patrol passing through our position. We couldn’t take the chance to intercept Clark at that time. As soon as the North Vietnamese unit passed through us, I slipped into the water and swam downstream to try and intercept Clark, but I couldn’t find him. Boy, that was a devastating feeling.

I gave the base a call and let them know that Clark got by us, and that the next radio check that Clark makes, tell him to just find a hiding position on the south bank of the river and we’ll pick him up. I gathered my team and sent them over ground. I went back in the water, worked all the way back downstream again. I saw movement behind an old sunken sampan and I knew it was Clark. The relief in his eyes was just inexpressible. We worked our way back to our forward camp and got him in the bunker.

A little bit later that day we got hit very heavily by North Vietnamese mortar rocket and small arms fire. So my team started grabbing bodies and throwing them under cover. Just pulling in the ones we knew we could do something with. By the time we finished we had Med Evac’d almost half of the guard force. Either they were killed or wounded during that assault. So we lost the majority of our support unit.

I was now left with three Vietnamese personnel to continue this rescue operation. We went out the next night and ran a mission to try and pick up Hambleton. That evening I had some problems with two of my Vietnamese. They normally had an officer, their chief. They knew what we were going through and they said, “We don’t want to do this.” I had to convince them. So they finally thought okay, but once they went back I was not going to use them again.

The third day an attempt to drop a survival package was made to Hambleton and it was dropped within 50 meters of him. He saw it but he couldn’t get to it. As the day went on it was reported from the forward air controllers that he was sounding very weak. They didn’t think he was going to survive much longer. That evening I told Kiet, the only Vietnamese there that was still working with me, that I was going to make an attempt to pick up Hambleton and he said that he would go if I would. He was a very brave man. We were going after an American and there was nobody there telling him to do that. His command was gone.

So that evening Kiet and I patrolled to an area where we had seen some sunken sampans and we found one that was floatable. A sampan is like a little canoe. We paddled upstream towards where Hambleton was. We ran into a fog bank and got turned around. By the time we busted out of the fog, it was early the next day. We came out just a little below the Cam Lo bridge, and there were troops on the bridge. From that position I knew exactly where I was, and I knew the general location where they thought Hambleton was. We found him fairly quickly in some shrubbery off the river bank. He was not in good shape. We loaded him in the sampan and covered him up with bamboo to make him look like a load of vegetation. Kiet and I were dressed like Vietnamese fishermen. We jumped in the sampan and started downstream.

We were seen by a North Vietnamese patrol, which had weapons. We kind of ignored them and looked like we didn’t hear them. At that time, you try to paddle as hard as you can without looking like you’re paddling as hard as you can. I was aiming for a curve in the river which would have put a bank between me and them, and they started chasing us. The vegetation kept them from staying along the bank. They couldn’t stay with us and they just let us go. I headed further downstream and we took heavy fire from a bunker complex at a bend in the river. We drove the sampan into the bank to give us some protection. I was on the radio with the forward air controller aircraft. I asked them to strafe both sides of the bank and to lay in a smoke trail to give us protection in case the fellow in that bunker made it through that assault. We pushed off in the sampan and by the time we came out of the smoke screen we were not that far from our base camp.

Once we had Hambleton back, we came under heavy mortar and rocket fire again, as we did every day. It was extremely bad that day. We had to call in aerial support. They did a tremendous job and we Med Evac’d Hambleton out of there. My next concern was Bruce Walker, who was still up there. Being a Marine, he did a superb job. He called in fire on a lot of positions, and he moved well, but he moved during the daylight and he was seen. A couple of bombers tried to come in and give him support but he was killed by the North Vietnamese. That whole effort was very costly to us. A lot of courageous people gave their lives to try and recover our own folks.

So both of you were given the Medal of Honor for a similar act of saving someone, someone you wouldn’t give up on.

Thomas Norris: Yes, sir.

When did you get your Medal of Honor?

Thomas Norris: My medal was not given to me until 1976. That’s a long time between action and medals.

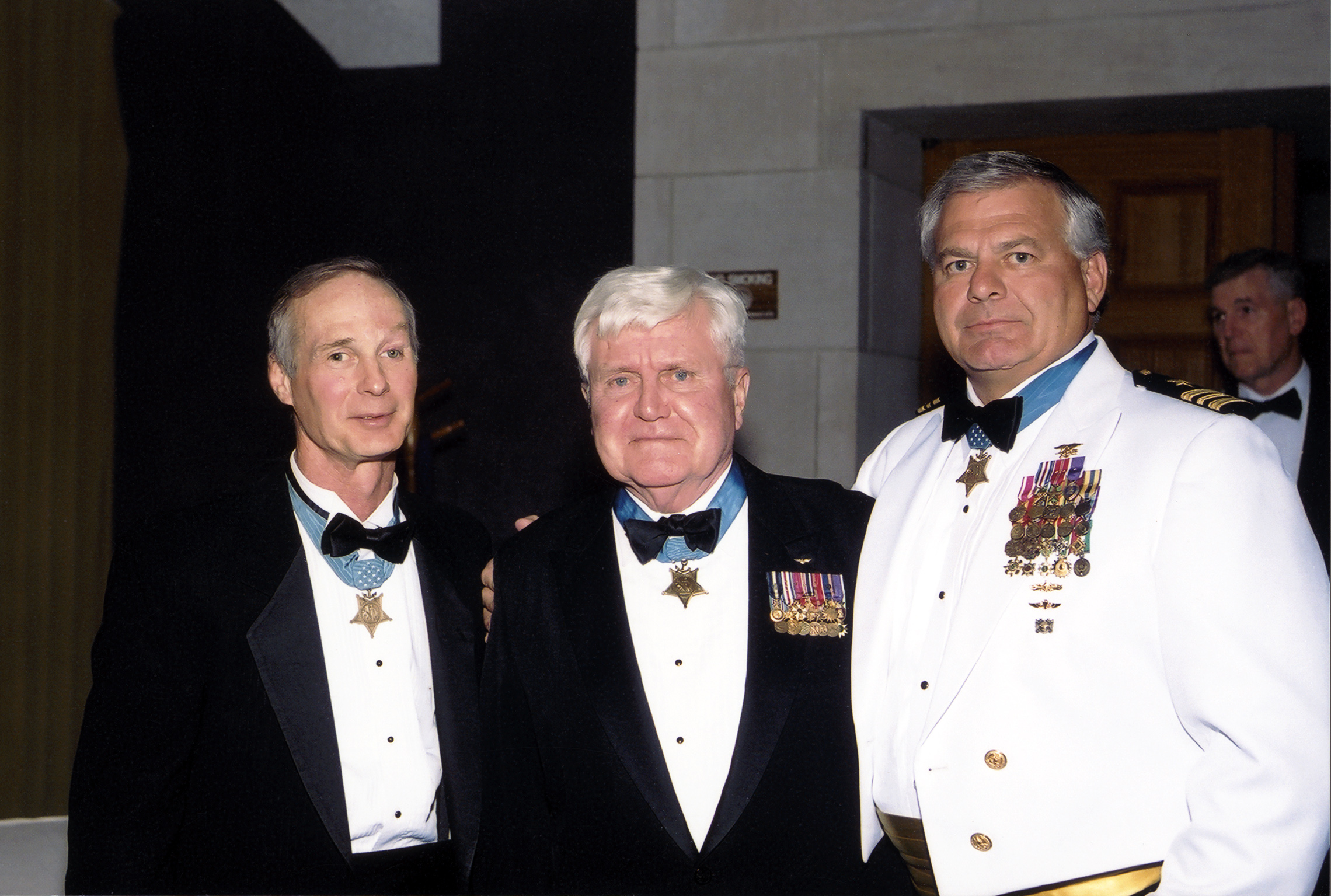

Michael Thornton: It goes through these different boards. We’ve had guys that have gone seven years without getting medals. Tommy received his with Admiral Jim Stockdale and Colonel Bud Day at the White House in March of 1976.

So you were there?

Michael Thornton: Of course I was there.

Thomas Norris: Part of the delay was when the teams wanted to have it reviewed because they thought that it was worthy of a higher award. I didn’t believe it was. I did what I had been trained to do and I was very fortunate in being successful. To me it didn’t rate that type of an award. The Awards Bureau disagreed with me and because of that I was a recipient of the medal.

Michael Thornton: This medal does not belong to me. This medal belongs to every man and woman who has ever served their country. And Tommy feels it. We were doing what we were trained to do. We were doing our job. Why we were chosen to receive this great honor, I don’t know. And you know, I don’t question it, but what I do — what I do and I let everybody in the world or the public know, is that this Medal of Honor belongs to every man and woman who gives us the freedom today to be able to hold our flag and hold our heads up high and say we have the greatest country in the world. And that goes with the men and women in the past, and the men and women of today, and the men and women of the future. As long as Mike Thornton lives, that medal will always stand for all them. Not for me. Not for what I’ve done, but for what I was trained to do and what they have been trained to do to give us our freedom today.

Thomas Norris: I feel much like Mike does. That medal does not belong to me. It belongs to all the soldiers over there that fought and lost their lives and were part of a conflict that they gave their lives for, or they worked for, as well as the teams. That medal was not mine. It belongs to everybody.

Gentlemen, thank you both, for everything you’ve told us and everything you’ve done.

Michael Thornton: Thank you so very much for having us here.

Thomas Norris: Thank you, sir.