The only thing I fear more than change is no change. The business of being static makes me nuts. I have to feel that each thing I’ve learned I can push to another point next time. I’m not very good with repetition. I would rather not work than feel repetition is the order of the day.

Twyla Tharp was born in Portland, Indiana, but moved with her parents to Southern California when she was still a child. The Tharp family owned and operated a drive-in movie theater in Rialto, California, and Twyla attended school in nearby San Bernardino. Twyla’s mother was a piano teacher who began to give Twyla piano lessons when she was only two. Twyla began dance classes at age four, and soon was studying every kind of dance available: ballet, tap, jazz, modern. Her mother was determined that she become accomplished in as many fields as possible and also had her take baton lessons, drum lessons, violin and viola lessons, classes in painting, shorthand, French and German.

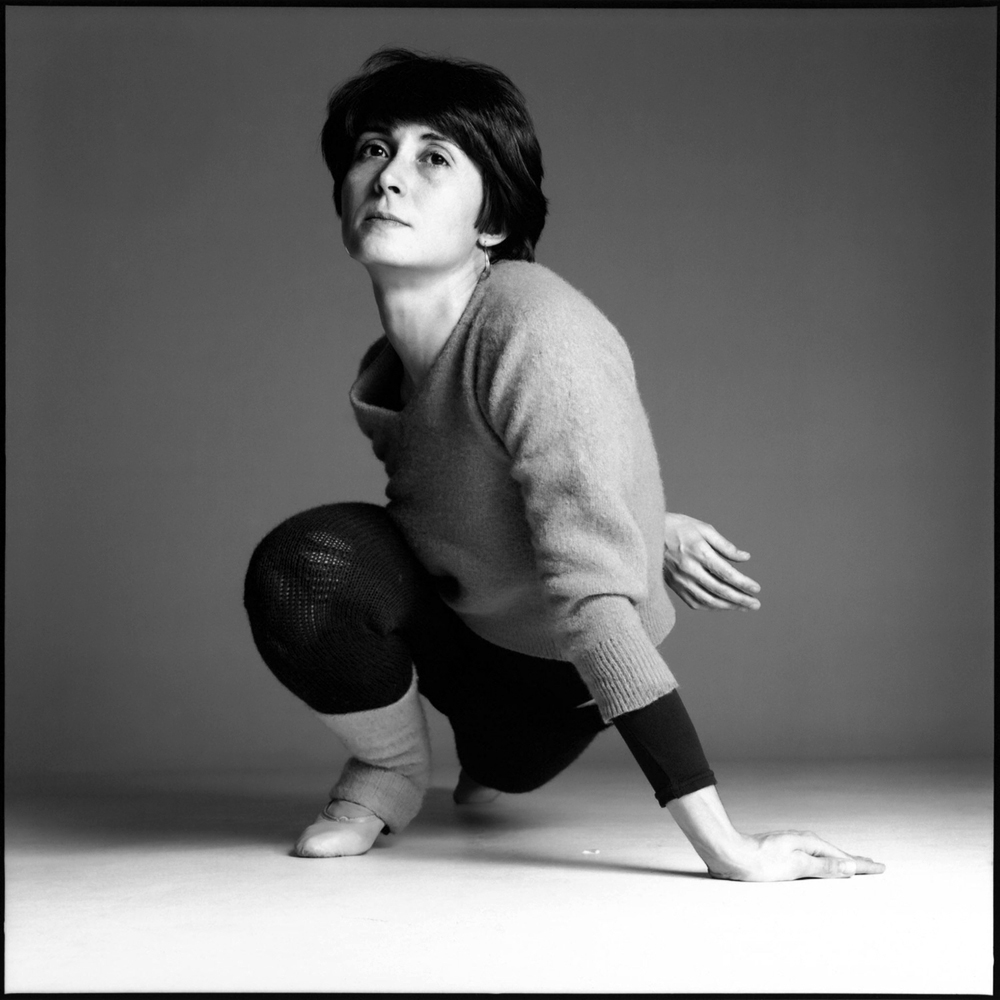

Twyla Tharp left home for the first time to go to Pomona College, but after three semesters, she transferred to Barnard College in New York City. At Barnard, Tharp studied art history, but found her passion in the dance classes she took off campus. In New York, she was able to study at the American Ballet Theatre school, and with most of the great masters of modern dance: Martha Graham, Merce Cunningham, Paul Taylor and Erick Hawkins. She completed her art history degree, but she had already resolved to make a career in dance. Shortly after graduation in 1963, she joined the Paul Taylor Dance Company, but within two years, she left to start her own group, Twyla Tharp Dance. This company, originally composed of five women (two men were added in 1969), worked ceaselessly for five years, performing wherever they could, earning little or no money for their work.

In the cultural ferment of New York in the 1960s, most young artists felt challenged to test the boundaries of their media. Twyla Tharp’s work fused classical discipline and rigor with avant-garde iconoclasm, combining ballet technique with natural movements like running, walking and skipping. While modern dance had historically aspired to high seriousness and spirituality, Tharp’s work was humorous and edgy. She worked less often with contemporary avant-garde music than with classical music, pop songs, a clicking metronome, or silence. Always, the choreography was dynamic, unpredictable and underpinned by an unusually thorough musical intelligence. This became apparent to critics and audiences alike with her 1971 piece, The Fugue. Her group was invited to participate in major dance festivals where works like The Bix Pieces and Eight Jelly Rolls grabbed audiences with their physical daring and deep roots in the history of jazz.

Twyla Tharp and many of her dancers were now invited to collaborate and perform with major ballet companies. The Joffrey Ballet premiered her Deuce Coupe (set to music by the Beach Boys), As Time Goes By and Sue’s Leg. At American Ballet Theatre, Mikhail Baryshnikov danced the lead role in Tharp’s Push Comes to Shove, which juxtaposed variations by Mozart with rags by Scott Joplin. The Russian ballet star and the young American iconoclast were a powerful combination and collaborated frequently in the following decades.

In 1979, she choreographed the dances for Miloš Forman’s film version of the ‘60s rock musical Hair. In the decades ahead, much of her work would appear on Broadway, beginning with an original Tharp production, When We Were Very Young, in 1980. The following year, she staged a full-length dance production, The Catherine Wheel, on Broadway, with music by David Byrne in his first venture as a composer outside of the rock band Talking Heads.

She continued to work in film as well, staging dances for the films Ragtime and Amadeus, both directed by Forman, and White Nights, starring Baryshnikov and Gregory Hines. Her 1984 television production, Baryshnikov by Tharp, won three Emmy Awards, as well as a Director’s Guild of America Award for her direction of the special. The following year, she directed and choreographed a stage production of the classic film musical Singin’ in the Rain. The show enjoyed a solid run on Broadway and a highly successful national tour.

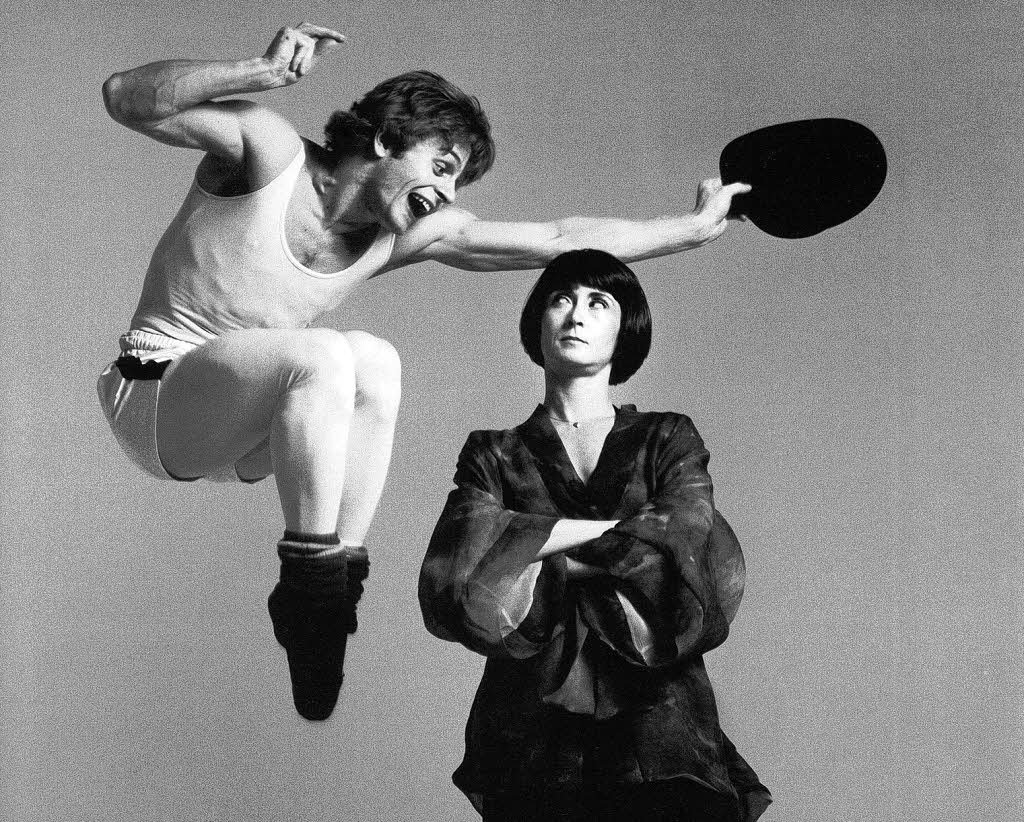

In the late 1980s, Tharp continued to create ballets at a slightly less hectic pace than before, while her past works became a staple of ballet companies around the world. In 1991, she reunited her company, Twyla Tharp Dance, with Baryshnikov joining the group in a program entitled Cutting Up. The work enjoyed one of the most successful tours in the history of contemporary dance. Twyla Tharp’s autobiography, Push Comes to Shove, was published in 1992. In the same year, she received a MacArthur Fellowship, one of the so-called “genius grants.”

At the time of her 1993 interview with the Academy of Achievement, she was preparing dances for the motion picture I’ll Do Anything, directed by James L. Brooks. Although the project was originally conceived as a contemporary musical, the studio cut all musical numbers from the film before its release. Returning to the world of pure dance, Tharp created new works at a feverish pace for the rest of the decade. From 1999 to 2003, Twyla Tharp Dance toured the world to enormous popular and critical acclaim.

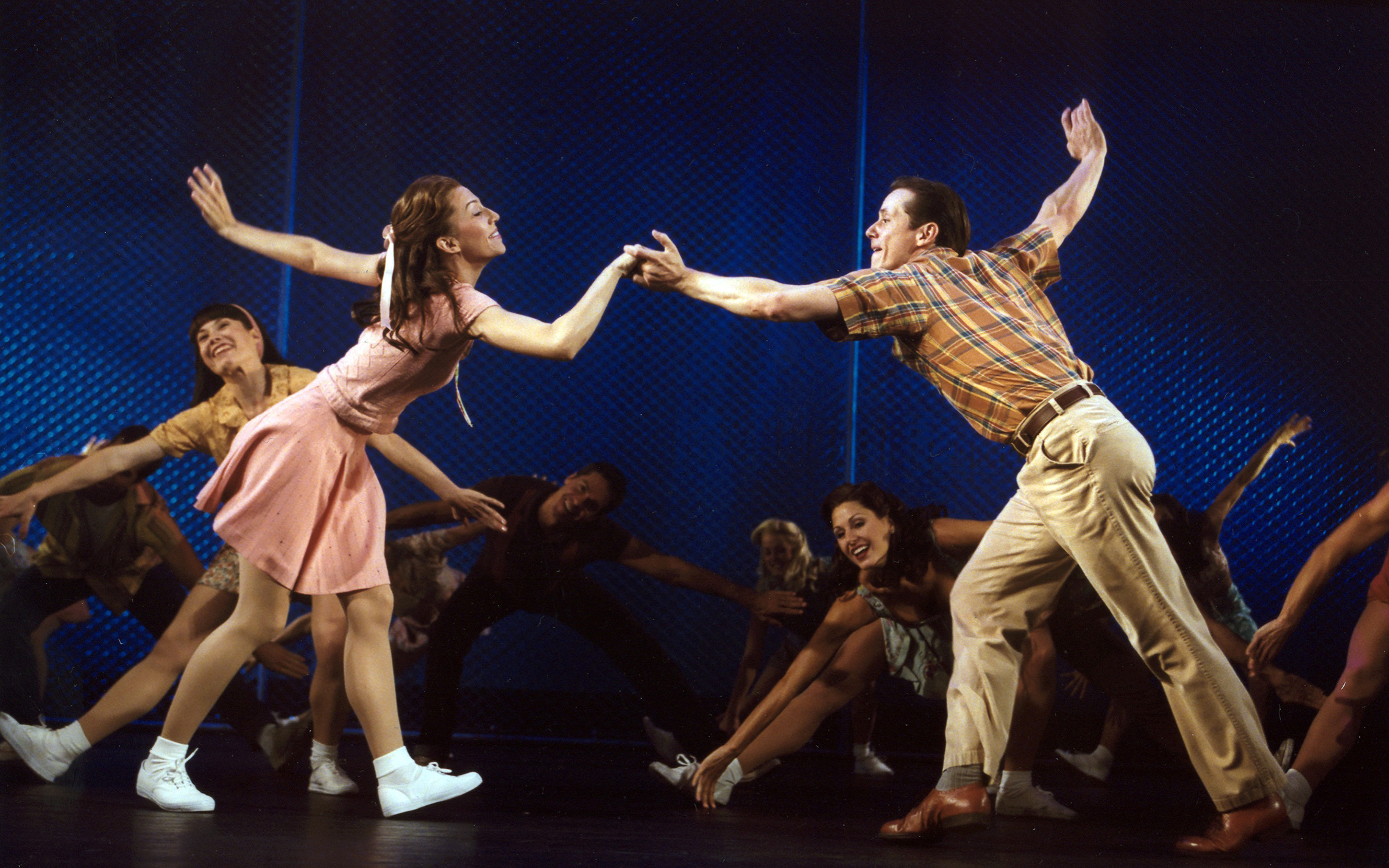

Tharp returned to Broadway in 2002 with an original dance musical, Movin’ Out, built around the songs of Billy Joel. The songs were performed by a singer and pianist, accompanied by a rock band placed above the stage, while a company of dancers acted out a story of young people living through the tumultuous events of the 1960s and ’70s. The show brought Tharp a host of honors, including the Tony Award. Movin’ Out became Tharp’s most popular creation to date, running for over three years on Broadway. A national company toured the United States for another three years and also made stops in Canada and Japan. In 2006, Tharp brought a second “jukebox musical” to Broadway, The Times They Are a Changin’, based on the songs of Bob Dylan, followed in 2010 by Come Fly Away, set to songs associated with Frank Sinatra.

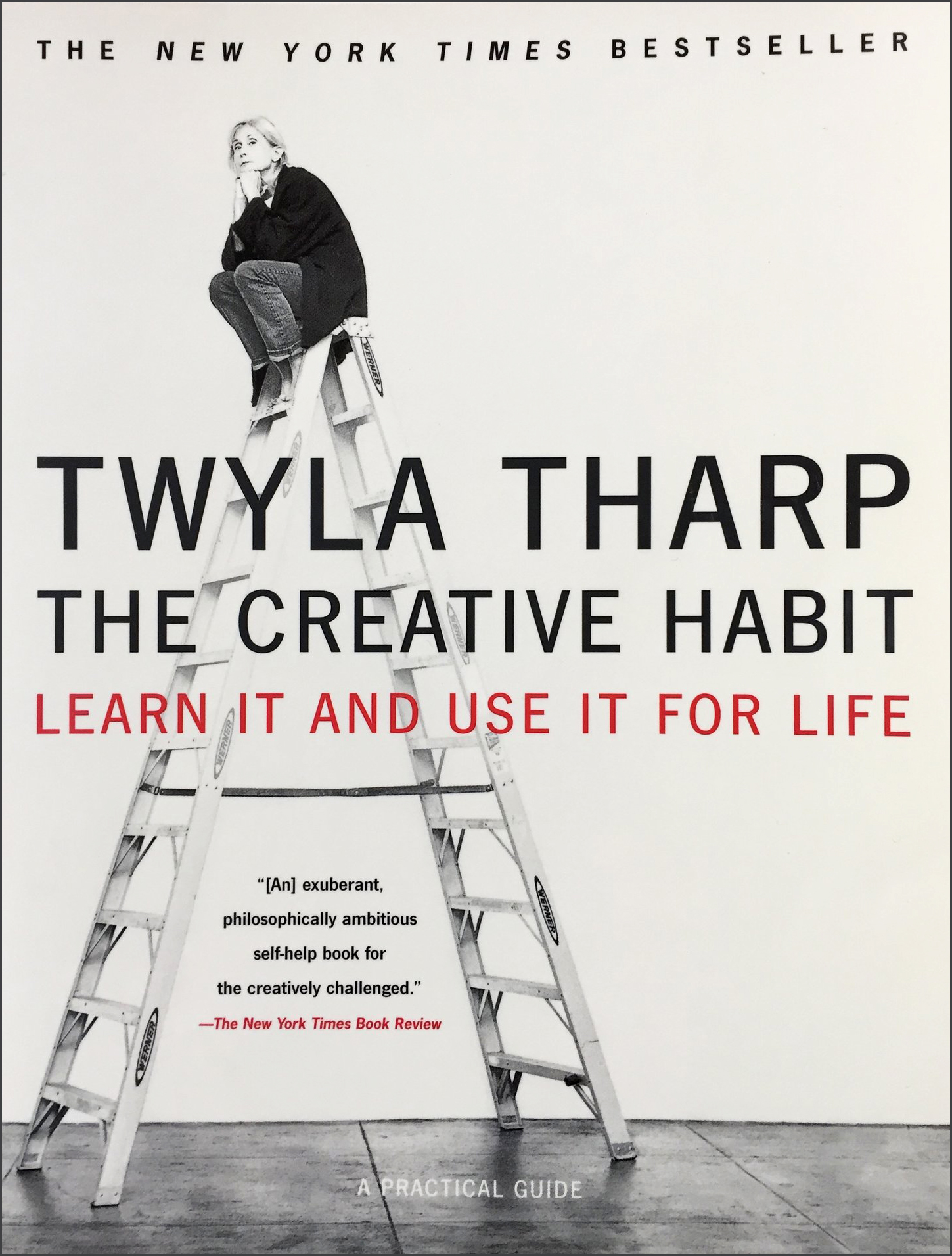

In 2003, Twyla Tharp published a second book, The Creative Habit: Learn It and Use It For Life (2003), in which she shared life lessons from her own career and those of artists throughout the ages. The Collaborative Habit: Life Lessons for Working Together, appeared in 2009. Her lifetime contribution to her country’s culture was recognized with the National Medal of Arts, presented by President George W. Bush in a 2004 ceremony at the White House. She received the Kennedy Center Honor in 2008.

Twyla Tharp’s prodigious creative energies are far from exhausted. As of this writing, she has choreographed over 160 works, including her work for Broadway, film and television. Every year, her pieces, such as Brahms Paganini, Brief Fling, Nine Sinatra Songs, Preludes and Fugues, and Beethoven Opus 103, are performed by ballet companies around the world. Her creative vision has had a pervasive influence on the work of younger choreographers and has permanently expanded the boundaries of contemporary dance.

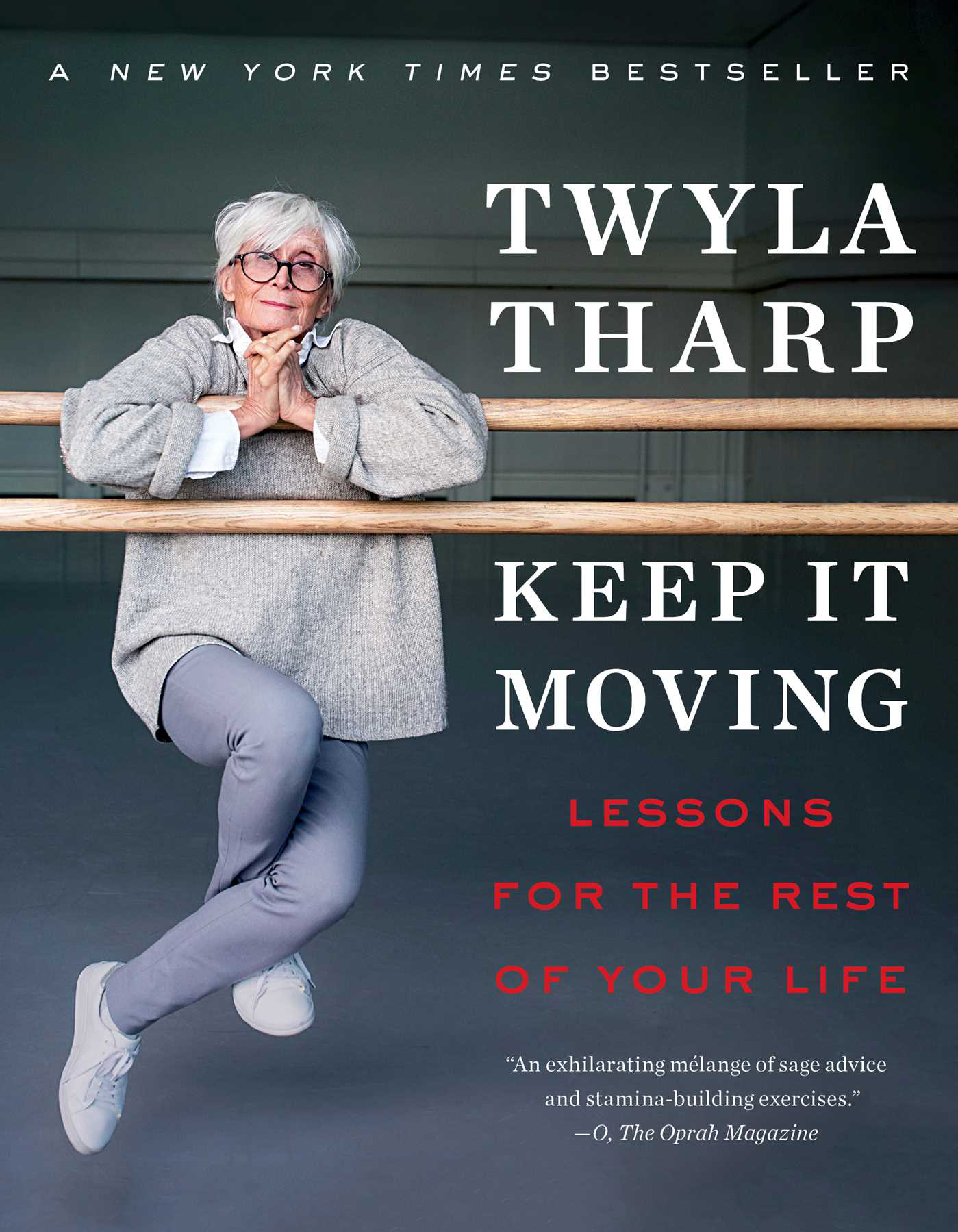

In 2019, Tharp published her fourth book, Keep It Moving: Lessons for the Rest of Your Life. When the COVD-19 pandemic shut down live performance and dance rehearsals, Tharp immediately began to explore the use of digital technology to create dance remotely. Within a year, she was creating new works online for Ballet am Rhein in Düsseldorf, Germany. In 2021, the public television series American Masters honored her 80th birthday with a two-hour broadcast, Twyla Moves. In addition to interviews and archival film, the program shows Tharp employing Zoom to stage a short version of her piece The Princess and the Goblin.

On November 2021, New York City Center marked Tharp’s 80th birthday with Twyla Now, an ambitious program featuring dancers chosen by Tharp from Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, American Ballet Theatre (ABT), and New York City Ballet.

In 2025, American Ballet Theatre honored Tharp’s six decades of innovation with Twyla@60: A Tharp Celebration, a landmark program that included her seminal works Push Comes to Shove, Bach Partita, and Sextet. Originally created for Mikhail Baryshnikov, Push Comes to Shove redefined the possibilities of classical ballet, blending virtuosic technique with humor, theatricality, and modern sensibility. The celebration affirmed Tharp’s profound and enduring influence on American Ballet Theatre and on the evolution of contemporary dance itself.

“I had to become the greatest choreographer of my time. That was my mission, and that’s what I set out to do.”

A large consensus of critics, dancers, and dance-loving audiences would agree that Twyla Tharp has succeeded in her mission. No one making serious dances in this country since the 1960s could ignore the challenge of her inventive, quirky, complex creations. No serious dance artist has ever stretched the boundaries between classical and popular, serious and silly, accessible and intellectual, as Twyla Tharp has. Even the arresting titles of her works convey their antic, inventive quality: The Bix Pieces, Deuce Coupe, Sue’s Leg, Push Comes to Shove, Cutting Up. When she first began to work with her own small company in the 1960s, Twyla Tharp brought more intelligence, humor, originality and nerve to the making of dances than New York had seen in a long time, and she did it at a time when New York was the undisputed dance capital of the world.

Twyla Tharp accomplished all this in her youth, when her own powerful dancing was one of her company’s prime attractions. Over the course of her career, she has choreographed over 160 works, from shorter dance works to evening-length ballets, along with12 television specials, four Broadway shows and six feature films. Her work has been recognized with honors ranging from Broadway’s Tony Award to the National Medal of the Arts.

When did you first have a vision of what you wanted to do?

Twyla Tharp: It depends on how you define vision. If it’s a sense of the way I enjoyed spending time most was dancing. It was from the time I was a very small child, when I puttered around the house. I was four or five years old, I remember already having a regimen. It was the way I always identified myself. If you’re speaking of professionally, it was not until I was after college, until I had graduated. So, it was much, much later that I made a professional commitment to it because, quite frankly, I didn’t think it wise. I was my own interior parental force, and it’s very difficult to justify a profession as a dancer… because it’s very difficult to earn a living; because there’s very little continuity, and because just when you arrive at the apex of your skills, it’s time to retire. And consequently, it seemed like perhaps a not wise investment of a substantial portion of my life. But as it turned out, I decided that since it was the thing that I felt I did the best, that I owed it to all that be to pursue it. That that was what I had to do, whether it meant I was going to be able to earn a living or not.

You felt there was a magnetic force there?

Twyla Tharp: You called it vision, I call it analyzing what my strengths were. It just so happened there was no market whatsoever for my strength, unless I was interested in becoming a show dancer, for which I tried, but I’m not tall enough. Also, when I auditioned for the Radio City Rockettes, they said, “We love your fouettés, but can’t you smile?” And things of that nature transpired between me and a commercial future. So, I managed to find a way of subsisting in the beginning by doing odd jobs, Kelly Girl temp work, selling perfume at Macy’s, and any and everything to be able to sustain studying and beginning a career with a group of dancers who were willing to devote five years, really, of their lives to me, working very seriously, with complete commitment, for not a penny. This is not a pleasant route for many young people to consider, I would imagine. Either you have to be either hopelessly passionate, I guess is the word that gets devoted here, or very stupid. None of us were very stupid; we were all college graduates, actually. But we all believed that we could make an impact on something that was very important to us, which was dancing and the future of dancing, and what could be accomplished. We determined we would do that.

I get a feeling you worked with your first company almost like a scientist in a lab.

Twyla Tharp: This is true.

We thought that there were certain possibilities, in terms of physical movement, in terms of community, and in terms of what dance could address in our society. And those were the issues that we went after. And we worked with a great deal of rigor. Which is to say, we were very, very dedicated. We worked six days a week, we worked at least six hours every day. We did not perform much at all. It was really about the experience of learning and exploring and growing, for five years.

Who were the dancers?

Twyla Tharp: For the first three years there were four, and for the next two years we were six.

You started with all female dancers. Why was that?

Twyla Tharp: In those days, male dancers, as they are still today, were a rarer breed than women. A good male dancer, a male dancer frankly as strong as we were, was very difficult to come by if you couldn’t afford to pay them because there was work that was available for them in all the major companies. That’s what we said, but the truth of matter is, we didn’t want them. Martha Graham also began her first company as all women. I think it’s because in modern dance, the female force has always been a very potent one. Modern dance in this country, in any case, is generally laid at the doorstep of female creators: Isadora Duncan, Ruth St. Denis, Martha Graham, Doris Humphrey. The next generation were men, but they spun-off from that generation of women. Erick Hawkins, Merce Cunningham, Paul Taylor, all came from the women because it was a primarily female force. I decided that we should not, in a way, pollute the experiment. It’s like mixed tennis. It’s a different game.

Men and women are very different athletes, and frankly, I didn’t want to deal with the male potential, I wanted to deal with the female potential. Plus which, obviously men and women bond very differently. And at that time we wanted to begin very simply. We used no costumes, we used no music, we had no partnering. We wanted just to explore movement in time and space. And in order to keep that experiment, as you’ve called it — which I think is accurate — pure, we determined that it should be sexually oriented only as women. And then after five years, the first man was introduced. And bit by bit I came to be much more interested in technical matters like partnering and so forth, until it’s become fully integrated.

But our partnering, for example, evolved in an entirely different way than it would have had we had men from the beginning. Because we had to develop a strength, not only physically, but emotionally, that is very different from how most women are when they’re partnered.

Twyla Tharp: I do weight training, and have for quite a while, and I’m much stronger than most women. Consequently, when I work with men, or when I’m partnered by men, I can do things no other women can do. Just in terms of counterbalances and how I support myself against him. And we can actually go into kinds of movement that haven’t been available before, simply because I’ve strengthened myself as a woman, not because I’ve weakened him.

Can you share with us some of the most exciting moments of your career?

Twyla Tharp: With each piece that I’ve completed I have worked to make it intact, and each of them has been an equal high. It’s like children. A mother refuses to pick out one as a favorite, and I can’t do any better with the dances.

I’m sure that as I’ve made major transitions, the rewards have been different. The rewards of dancing, myself, are very different from choreographing. The rewards of working with dancers you’ve worked intimately with is very different from dancers that belong to a company you go into. The rewards of extending your discipline and incorporating whole new elements. For example, as I begin to try to deal with film and the element of storytelling, and putting a dramatic narrative at the spine of the action, rather than simply abstract time and space, this is a very big shift, and I’m sure the rewards will be different.

But the reward that I felt for doing a piece called The Fugue in 1970 will never be surpassed. Because I knew then what an accomplishment it was and how far I had come in order to be able to make counterpoint, which is what that represented. How to link two lines in relationship to one another, so that they were bound, and reinforced one another. You give your own accomplishments, and that’s what reward is about. It’s not about honors, it’s not about celebrity, it’s certainly not about money.

Was there someone who gave you a big break in your career?

Twyla Tharp: Yes. I would say that for the first five years I pretty much seized things. But Bob Joffrey saw a piece of mine called The Bix Pieces at the Delacorte around 1971. From that piece, he had the breadth of vision to see that what I was doing could be translated to what his dancers understood. I already knew this, because I had been studying classical ballet for a long time. But a lot of people insisted on a wall between modern dance and ballet, that the two disciplines were totally separate, and if you did one, you couldn’t do the other. I’m beginning to think that walls are very unhealthy things. Bob saw that what I did had a very strong balletic base to it, and he asked me to make a piece for his company. That took a real leap of faith on his part. This is what is ordinarily called a break, because it certainly is what introduced me into the commercial world. From there I made another piece for the Joffrey called As Time Goes By. After that I did Push Comes to Shove for American Ballet Theatre with Baryshnikov. Miloš Forman saw that piece and asked me if I would do the movie of Hair. From Hair I was able to begin working in pictures and to extend my career into television. Now I am very fortunate because I am in a position where I need to expand the definition of movement much beyond the parameters of what can be accomplished in dancing, per se.

Did you have any idea that Deuce Coupe would be the hit that it was?

Twyla Tharp: There are ideas, and then there are ideas. The piece was not without a certain amount of calculation. That’s the first piece I did for the Joffrey. I went for a season to watch the Joffrey Company and the Joffrey audience, before I made the piece. It was very distinctly tailored for both the audience and for the company. On the other hand, it is extremely arrogant and very foolish to think that you can ever outwit your audience. And all you can do is make your sincerest stab at saying, “Hey, I think you could understand what I’m trying to say if I say it this way. I think I know you well enough that this is how I need to say it for you.” I don’t consider that selling out. I consider that going halfway to meet a person, and I consider that to be what communications is all about. Deuce Coupe was very successful in that regard. As far as watching, I was in it. So I was too busy hopping around backstage to have any sense about what it was doing to the audience out front. I was having too much fun.

You also elevated pop music, using the Beach Boys’ songs in that piece.

Twyla Tharp: Again, I’m not one who divides music, dance or art into various categories. Either something works, or it doesn’t. I don’t mean this, but I’m going to say it anyway: I don’t really think of pop art and serious art as being that far apart. That is a total lie. I think of them as being completely different, and I don’t think of them as being that far apart. This is one of the things that we have to accept about art is that it’s full of paradoxes and contradictions, and they’re equally true, both sides.

Since your early great work with female dancers, you’ve worked with some notable male dancers, like Baryshnikov.

Twyla Tharp: Mischa is a great dancer.

It’s also, I think going to be true that the 20th century is the domain in the classical ballet of the classical male dancer in a way that it never was before. It was always about the ballerina. Part of that is because the choreographers were always men. Consequently, they shaped the roles for women as they wished them to be. When I started choreographing for classical ballet companies there had been, before me, two women who had ever made a ballet on a classical company. So, of course, I’m interested in the male dancer. Plus which, not only Mischa (Baryshnikov), but Rudi (Nureyev) was a virtuoso, and (Edward) Villella. There are these days, young men dancing who have a power and potency that we respond to because of athletics. We’re trained, unfortunately, and indoctrinated in the facts that the male physicality can be marketed in a way the female cannot. Consequently, you have the multimillion-dollar athletes in the male world, and practically none in the female. This has had an impact in the dance world. The stars there in the classical world these days are men. I was fortunate to love men, so I could put them on stage and make roles for them, and move through their bodies in a way that they enjoy doing that they responded to, as the ballerinas have to male choreographers for centuries.