The nerve of failure I think is paramount. Learning by mistakes, modifying, reconstituting, reorganizing.

Wayne Thiebaud was born in Mesa, Arizona, but his parents moved to Long Beach, California when he was only six months old. He would spend most of his youth in Southern California, but his large Mormon family had deep roots in the desert Southwest, and the young Wayne Thiebaud also spent a number of years living on an uncle’s ranch in Utah. His early enthusiasm for comic strips and illustration led to an interest in serious art. Although he showed a precocious talent for drawing, fine art training — or even a college education — seemed like remote possibilities in the depressed economy of the 1930s. One summer between terms in high school, a teenage Thiebaud found work at Walt Disney Studios as an “in-betweener,” laboriously drawing the thousands of individual frames that gave the illusion of movement to animated characters. The following summer, he enrolled in the Frank Wiggins Trade School in Los Angeles with the intention of learning sign painting. Experienced commercial artists in the school encouraged him to study illustration, and he set himself to learning the skills of a commercial artist.

His budding career as a cartoonist and graphic designer was interrupted by World War II. From 1942 to 1945, Thiebaud served in the U.S. Army Air Force, where his skills as an artist kept him out of combat. During the war, he met and married Patricia Patterson. Their first child, Twinka, was born in 1945. A second daughter, Mallary Ann, was born in 1951. After the war, Wayne Thiebaud resumed his career as a commercial artist, working for the Rexall drugstore chain, among others. At Rexall he met a fellow commercial artist, Robert Mallary, who was also an aspiring fine artist. Mallary encouraged Thiebaud to study fine art, and to broaden his education generally. Nearing 30 years of age, Thiebaud enrolled in the California State University system, first at San Jose and then at Sacramento, where he earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees. Thiebaud had set himself a new goal, to support his family by teaching while pursuing a career as a fine artist. He found work at Sacramento City College, where he worked throughout the 1950s.

Thiebaud spent a sabbatical year in New York City, where he made the acquaintance of the leading American painters of the day. Among these were the abstract expressionists Willem De Kooning and Franz Kline, as well as Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns, two painters whose work would later be identified as cornerstones of the pop art movement.

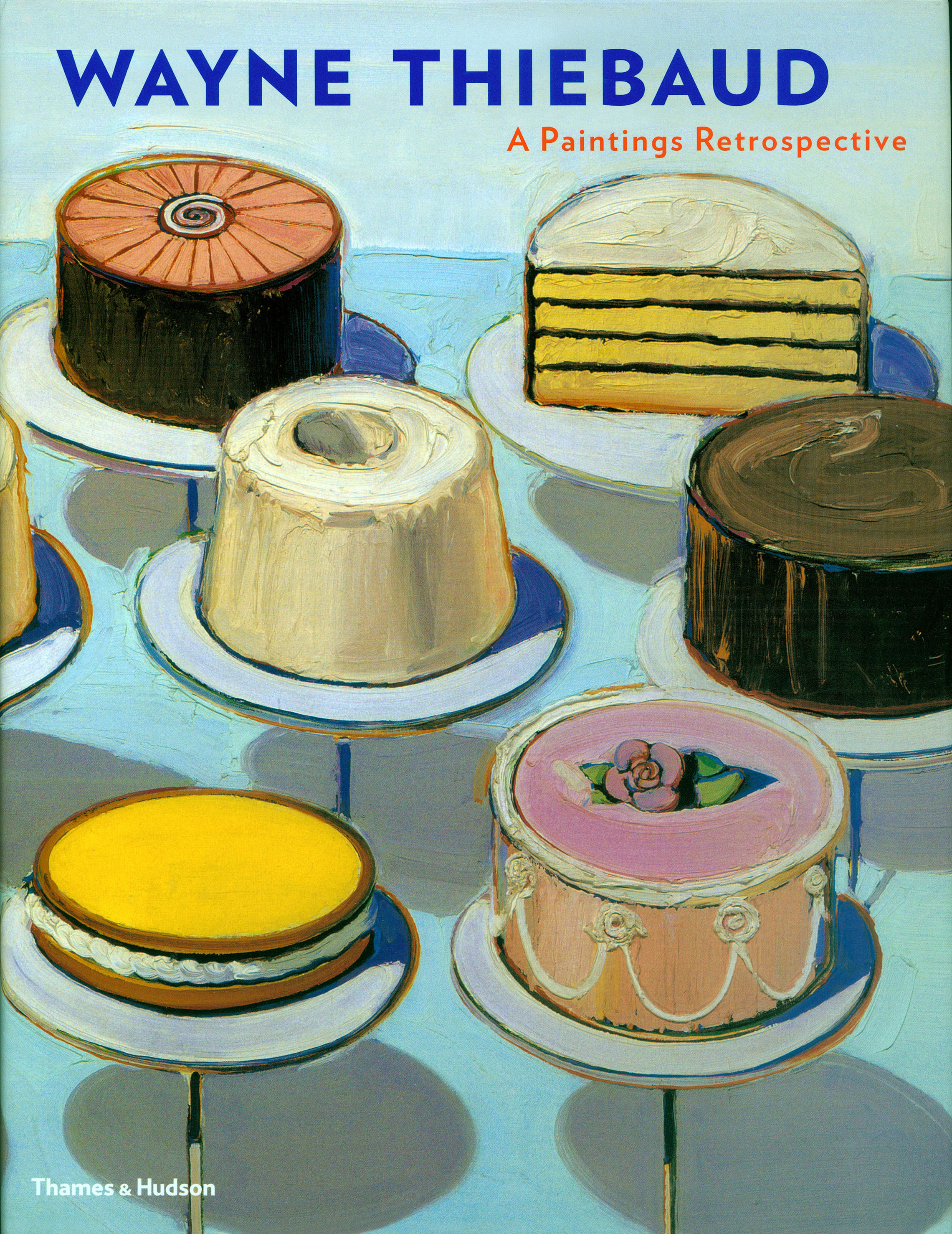

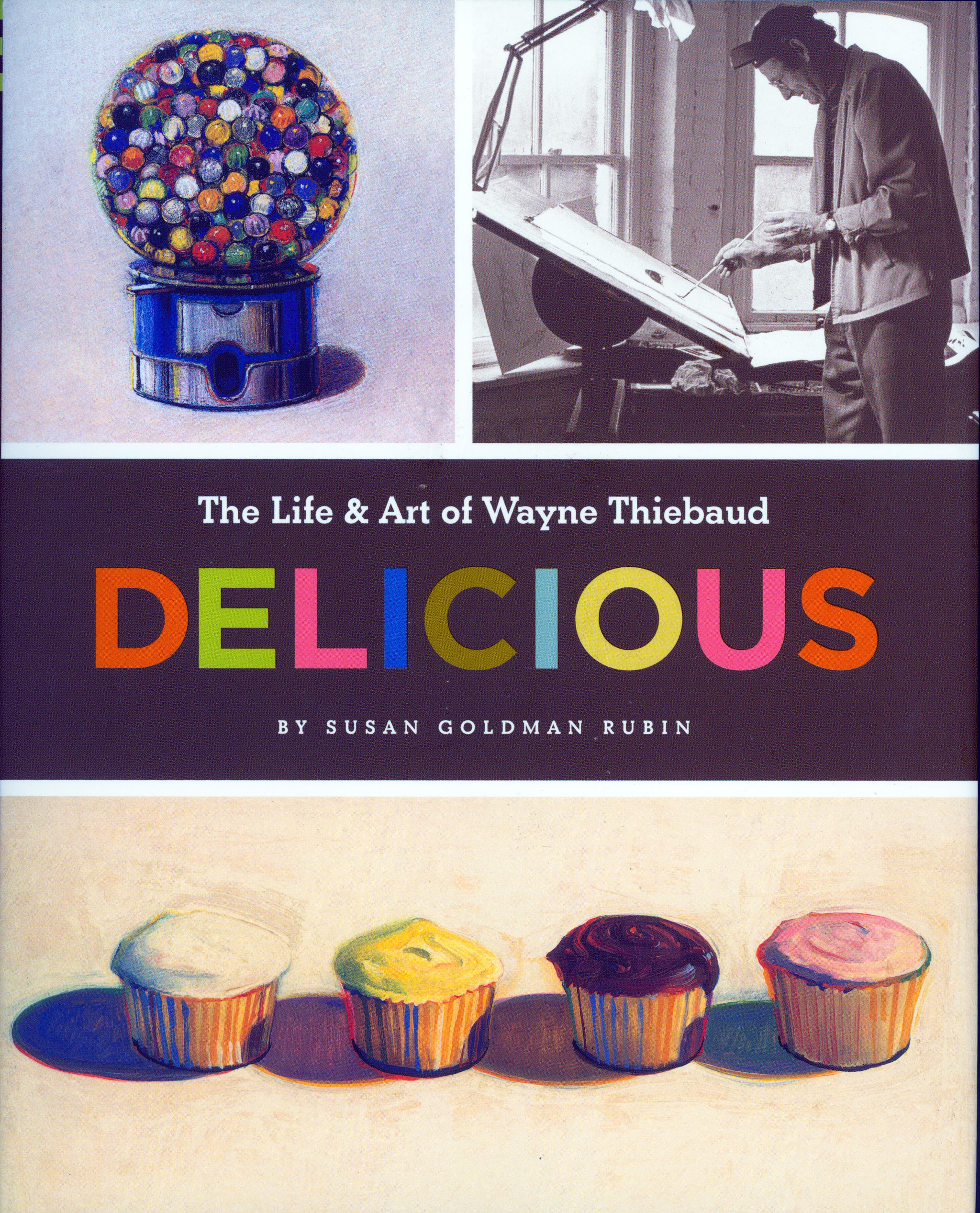

At this time, Thiebaud found a way to apply the formidable technical skills he had acquired during his years as a commercial artist to a new and unique subject matter. He began to paint small canvasses depicting brightly colored food products — pies, cakes, candy and ice cream cones — displayed as in shop windows, meticulously rendered with multi-hued outlines and the hyper-realistic shadows characteristic of commercial art. While conventional still lifes are painted with the artist observing real objects as he paints, Thiebaud drew his pictures of food entirely from memory and imagination, a practice that contributed to the dreamlike intensity of his vision.

There were no galleries to speak of in Sacramento in the 1950s, so Thiebaud exhibited wherever he could, in shops and restaurants, even in the concession booth of a drive-in theater. Impressed with the artists’ cooperatives he had observed in New York, he founded a cooperative gallery in Sacramento, now known as Artists Contemporary Gallery, and an artists’ retreat known as the Pond Farm. In 1958, Thiebaud and his wife Patricia divorced. Their daughter Twinka became a celebrated artist’s model, author and painter in her own right. Wayne Thiebaud later married filmmaker Betty Jean Carr, and adopted her son Matthew, who also became an artist. The couple had a second son, Paul, who became a noted art dealer and gallerist.

Thiebaud’s work was making an impression on his colleagues but had not yet found a general audience. This began to change in 1961, when he met the New York art dealer Allan Stone. Stone was initially indifferent to the slides he saw of Thiebaud’s food paintings, but when the artist contacted him again a year later, Stone remembered them vividly and agreed to represent him. Stone became his exclusive dealer and a close personal friend. His first showings at Allan Stone Gallery resulted in major sales. In addition to showings at Stone’s gallery, Thiebaud’s work was featured in two historic group shows in 1962. The Pasadena Art Museum’s “New Painting of Common Objects” is regarded as the first exhibition of pop art in America. Thiebaud’s paintings were included alongside the work of Roy Lichtenstein, Jim Dine and Andy Warhol — an artist with whom Thiebaud felt little affinity — but the exhibition attracted national attention and made Wayne Thiebaud a major name in the art world. Later that same year, the Sidney Janis Gallery in New York presented an “International Exhibition of the New Realists,” which again grouped Thiebaud with Warhol and Lichtenstein, as well as James Rosenquist. Coming on the heels of the Pasadena exhibit, the show at Sidney Janis made pop art the dominant visual style of the ’60s.

Thiebaud never embraced the concept of pop art, often characterized as a parody or critique of commercialism and consumer society. Thiebaud preferred to describe himself as a traditional painter of illusionistic form, and regarded the craftsmanship of advertising, cartoons and commercial illustration with respect and affection. He also distinguished himself among his contemporaries through his exacting craftsmanship and his uncompromising dedication to his own vision, without regard for changing fashions or trends in the art world.

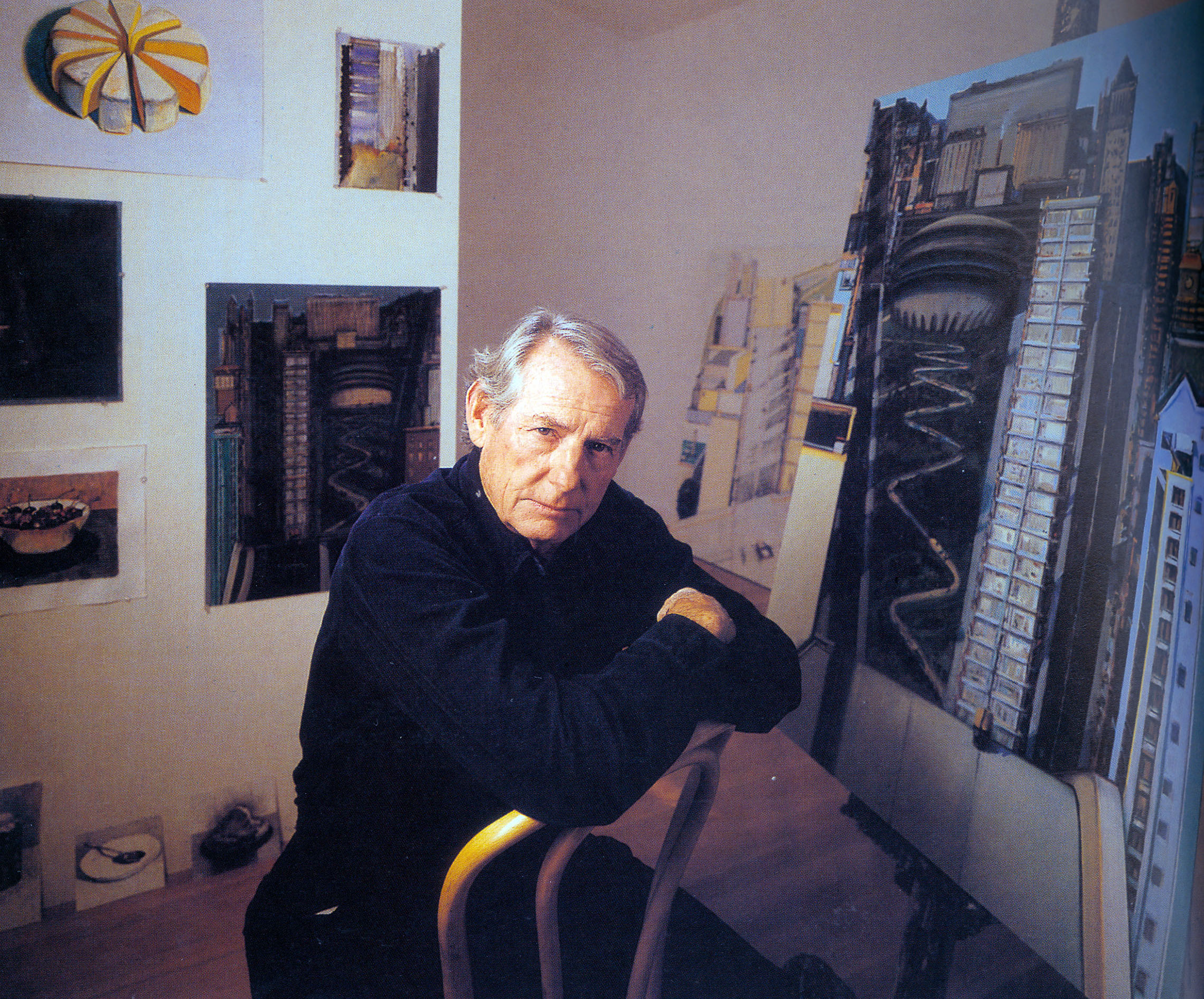

As other artists adopted the now accepted pop art motifs, Thiebaud turned increasingly to the representation of the human figure, rendered in meticulous detail, but with a dispassionate sense of weight and solidity that freed the painted figure from any implication of sentimentality or superficial appeal. In the mid-’60s, Thiebaud also took up printmaking, a practice he has pursued alongside his painting ever since. In the 1970s he carried on with his examination of everyday objects, including shoes and cosmetics, while painting his first major landscapes, dizzying street scenes inspired by the vertiginous topography of San Francisco. He continued his landscape series for the next 20 years, finding haunting beauty in apparently commonplace scenes, rendered with hyper-realistic detail.

He has received numerous honors for his work, most notably the National Medal of Arts, presented to him by President William J. Clinton in a 1994 ceremony at the White House. A 2001 retrospective of his work at the Whitney Museum in New York won enthusiastic acclaim. After the death of Allan Stone in 2006, Thiebaud was represented by his son, art dealer Paul Thiebaud, until Paul’s death in 2009. Although Wayne Thiebaud retired from full-time teaching at age 70, his decades of mentoring younger artists has had a major influence on American art. Many of his students have enjoyed distinguished artistic careers, not the least of whom was the late Fritz Scholder (1937-2005). At age 100, Wayne Thiebaud was still painting; his centennial was observed with major exhibitions in Sacramento and San Francisco. His vast body of work continues to inspire and delight viewers with its unique vision of the charm and beauty of everyday things.

(See a video montage of the paintings of the American master artist Wayne Thiebaud.)

In 1960, painter Wayne Thiebaud’s brilliantly colored images of pies, candy and hot dogs seemed worlds apart from the severe abstractions then fashionable in the serious art world. But when a New York gallerist took a chance on the struggling Californian, his paintings sold like proverbial hot cakes. Today, his canvases hang in the world’s great museums, and routinely fetch millions of dollars at auction.

For half a century since, Thiebaud has continued to paint, print and draw, finding an otherworldly beauty in the everyday objects of this world: food, clothing, shoes, tools, city streets. The representational skills he learned as an illustrator and cartoonist in the 1930s and ’40s, combined with a keen critical sense and a thorough command of the history and traditions of painting, have given his work solidity and staying power that transcend the changing tastes of the times.

Wayne Thiebaud has shared his gifts with the world, not only as a working artist, but over a lifetime of teaching, developing the skills and critical faculties of succeeding generations of artists. His paintings, seen firsthand, convey a visceral delight to the beholder, while his works in reproduction have indelibly colored our view of the American landscape.

Let’s talk about your first New York show. It was at the Allan Stone Gallery, wasn’t it?

Wayne Thiebaud: The first New York show, yes. That was in 1962.

And was that where you sold your first paintings or was it prior to that?

Wayne Thiebaud: No, I had sold paintings. I’d sold lots of paintings locally to wonderful people who were supportive, in Sacramento and other places. But these newer paintings, they were troubling to people, and understandably so.

Which ones are we talking about?

Wayne Thiebaud: Pies and cakes and the hot dogs, those things. So Allan also — Allan Stone, the dealer — was very puzzled by them, and it took him a year or two to get to a point of saying, “Before I got the courage to show the damn thing,” was the way he put it. And that’s quite a mark of his ability and loyalty, to take me on and see what he could do. We didn’t have very many hopes. He said to me, “I think you’re a good painter. I don’t know about these, but we’ll show them and we’ll show them. I’ll try to get a plan of about five to ten years where we keep showing things of yours in the hope you gain a kind of clientele.” And that’s what we did. So it was a big shock to find that, serendipitously, pop art came in, and we were sort of shunted into that sudden interesting world, that is, interesting to critics and interesting to people. And that’s how really it occurred.

Let’s talk about the subject matter that you originally became famous for. Those desserts and shoes, gumballs. What inspired you to adopt that subject matter?

Wayne Thiebaud: I can’t take any credit for any theoretical or philosophical awareness of it.

It was somehow important to me to be honest in what we do, and to love what it is we paint. These were lessons given to me by other artists, obviously. To do what you love, or are interested in, or have some regard for. And it seems to me that it’s easy to overlook what we spend our majority of time doing, and that’s an intimate association with everyday things: putting on our shoes, tying our ties, eating our breakfast, cooking our meals, washing our dishes. Somehow that ongoing human activity seems to me very much worth doing. It’s only when we become presumptive, I think — to think we’re better than that, and we’d like to be, and should think of ourselves being better — that we begin to ignore those things. But in a wonderful way, children really remind us of it. They go to the gumball machines with their little penny and put it in and say, “Look, Dad!” Look what came out of this terrible-looking thing, this magenta sweet little whirl of wonder. And that, to me, is as good as we get.

There seems to be almost a humility about that.

Wayne Thiebaud: I don’t know if it’s humility. I think it’s just good stuff.

Gazing at your paintings of cakes and pies, the first thing that strikes one is how delicious they look. There’s a welcoming, pleasurable aspect to these paintings.

Wayne Thiebaud: Well you know, bakeries and display people are very good at making them look almost transcendent, just like they do with diamonds. I mean how many lights they put on them to make them sparkle so much, or used car places where they have a row of lights to light them up and make them sparkle.

You do that too in your own way.

Wayne Thiebaud: Yes, I hope so. What’s the use of making something and making it look bad?

In many of these paintings there’s repetition. Not just one piece of pie, but a showcase of pies.

Wayne Thiebaud: Well, it has to do with the tradition of painting, of orchestrating a single shape into its various configurative potentials. If you look closely, they look all alike at first, until you examine them. Each one is curiously different in some minor way. That orchestrating principle you can find all through the tradition and history of painting, because it’s an obvious design concept. It’s like a drum beat, you know, slight variation, repetition, rhythms and so on.

Is there also a connection to commercial art?

Wayne Thiebaud: Very much so, yes. After all, they’re trained in the same skill as the fine arts. They’re very, very good at what they do, and they’re very artful in what they do.

We still, I think, haven’t got the categories fully straightened out about fine art and commercial art. We like to think we have, but I don’t know. It’s proven to be, actually now, that American illustrators of a certain quality are commanding very high prices all of a sudden, because they’re so damn special. And if art — if the character of art — doesn’t contain the idea of specialness, rare achievement, and of a certain limited convention, then I think we’ve got it wrong if we don’t celebrate anything which makes and comes to these rare achievements.

You grew up in Southern California, but you also spent some time on a ranch in Utah. Your uncle was a maker of roads and so forth. Do you think these were formative influences on your art, where you grew up and the things you observed?

Wayne Thiebaud: I’m sure that’s true in some way. I was lucky to have a lot of good uncles. My grandmother gave birth to 11 children and they all married, so a great range of people, great aunts, great uncles, all this kind of interacting family, quite active.

A close family too?

Wayne Thiebaud: Yes, they always were sort of close together, a lot of them. Essentially, it’s a Mormon-based family. So that sort of clannish one is much like any religious company that was sort of terrorized by prejudice and so on. So it made it even a closer-knit family, I think.

Were there artists in the family?

Wayne Thiebaud: No, not that I know of. Mostly farmers, businessmen, traveling salesmen, fishermen, a huge, very nice range of differences.

What about your parents? What kind of work did they do?

Wayne Thiebaud: My father was a mechanic-inventor, and mother, a homemaker. I was a spoiled child. And they couldn’t have been a greater psychological base to give me the kind of ego I have.

In what sense?

Wayne Thiebaud: Just that I felt I could do anything I wanted. And that made me a very poor student, because they didn’t check on grades. Even though my grandfather came from a kind of quasi-intellectual tradition, he was a school teacher and then the superintendent of schools, and later became a kind of practicing inventive farmer. So it was a long range of influences and interests.

Where was your uncle’s ranch? Was that in Utah?

Wayne Thiebaud: Right, in South Utah, between St. George and Cedar City, sort of red earth country, very beautiful. Probably had a lot of influence on interest in landscapes, very beautiful country in so many different ways.

You kind of ricocheted back from Southern California to Utah and then back again, I gather.

Wayne Thiebaud: Yes. Mostly Southern California, about three or four years spent on a ranch in Southern Utah.

You liked sports as a kid too, didn’t you?

Wayne Thiebaud: Always.

Did you play organized sports?

Wayne Thiebaud: I did in high school, and junior leagues, and it’s always been pretty central to what I do.

What sports did you play back then?

Wayne Thiebaud: Basketball early on. I came to tennis very late, but I played almost all sports: baseball, softball, track and field.

How late did you come to tennis?

Wayne Thiebaud: I must have been 40 years old before I ever played tennis. That’s why I have such a rotten game.

You’re still playing, of course.

Wayne Thiebaud: Still playing, but it’s what you call a public courts game, just with no lessons in the beginning, which can ruin your game.

It’s interesting that you’re still committed to exercise and sports. Do you think there’s a relationship between the body and art?

Wayne Thiebaud: Very much so, central. It’s what Gloria Steinem identifies as the most revolutionary human emotion, that is, empathy. And since the body is the measure of empathy, it’s crucially central to the kind of critical concern about the inner workings of a painting: its thrust, its spatial illusionism, the coherence with which we judge balance, symmetry, tension, grace. Those are all based on a body, its feel, extremities, those kinds of things.

Scale, as well?

Wayne Thiebaud: Scale, absolutely, yeah.

If you’re not participating with your body when you’re looking at a painting, whether it’s a Cezanne — which has to do with a kind of equivocation, ambiguity, a sense of alternation — or in the case of someone like Velazquez, where the physical attributes of his painting, the knowledge that he’s showing you, and the feeling which he’s expressing, that’s all about the body, whether it’s sitting well, a state of tension, whether that heel really feels like it’s gripping the ground or expressing that contact. All of those we measure really by — in my judgment — the body and its issues.

So you want to feel as connected to your body as possible, as an artist?

Wayne Thiebaud: Yes. That’s why I have difficulty in convincing students to stand when they paint, rather than sit, for instance. There’s a real difference in the character of gesticulation and location, things like that.

Going back to your childhood and school years, were there particular books you read that were important to you?

Wayne Thiebaud: Lots of books, but I wasn’t a great student or a great reader until quite late. I was bored at school, so that wasn’t something I could get any interest in, to the disgust I think of my teachers who were always sending notes home. “Wayne is not dumb, but he won’t do anything.” So that was a real misfortune actually, and to my disgrace, I came to learning very late, in the sense of literature or all the things I later began to treasure.

But not too late.

Wayne Thiebaud: Hopefully.

When did you first begin to see yourself as an artist?

Wayne Thiebaud: Never. I don’t like the term “artist.” It’s a term which I’m uncomfortable with, but I love the idea of being a cartoonist, a draftsman, a designer, a painter — those other things which we make clear objective information about. So the idea of being a fine artist came very, very late, and came by way of examples of people who I became aware of, their extraordinary achievements.

Like who?

Wayne Thiebaud: It began really with cartoonists. A great example would have been George Herriman, the creator of Krazy Kat. Extraordinary man and extraordinary artist. When you use the term “artist,” then you’re talking about the highest achievement within each of those categories. But then, slowly, all of the painters. I read a book which meant a lot to me, Van Loon’s Artists’ Lives, talking about Rembrandt and those kinds of people. I never imagined myself ever even getting to a point where I might be able to pursue those things. But I still had this awe of artists. And again, you go to museums a lot, read more, particularly biographies and artist biographies. So as I said, I came to it quite late.