There was a magical breakthrough when the computer became cheap and we could see that everyone could afford a computer.

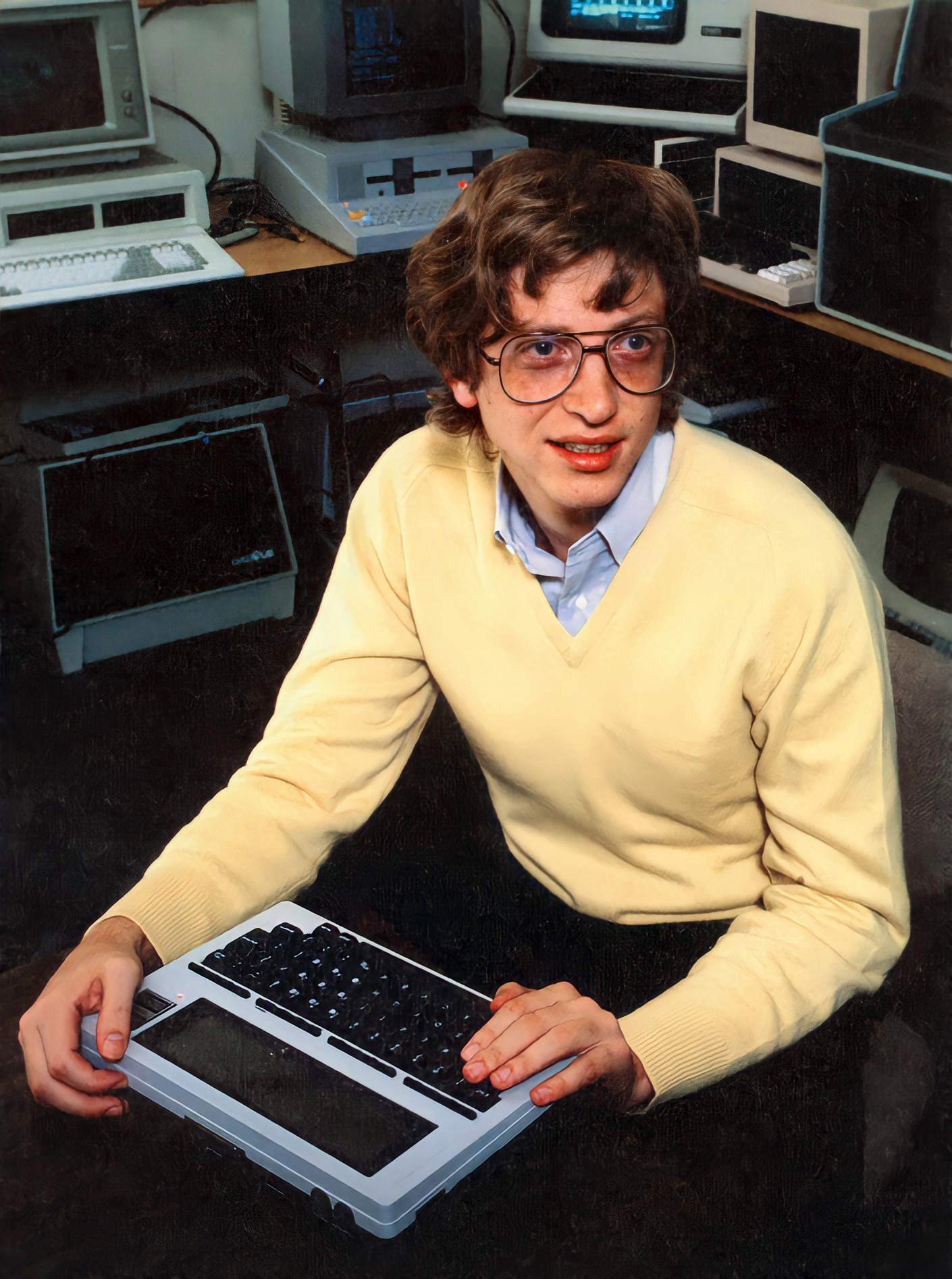

William H. Gates III was born in Seattle, Washington, the second of three children, in between an older and a younger sister. His father was a successful attorney, and it was expected that young Bill would follow in his father’s footsteps. He was a notably gifted student who did well in all subjects but showed a special aptitude for mathematics. When he was 13, his parents believed he was not being challenged in his public school and enrolled him in the private and highly demanding Lakeside School. The school acquired a computer terminal, and young Bill Gates was immediately fascinated. He and a small group of friends, including his future business partner Paul Allen, took every opportunity to explore the possibilities of the new technology, teaching themselves the basics of computer programming.

Soon Gates and his friends were working part-time and summers, writing computer programs for large businesses around the Seattle area. Although they were all precociously gifted programmers, it became clear that Gates had a unique talent for business as well, and he quickly emerged as the leader of the group. Gates and Paul Allen closely followed events in the computer industry and foresaw that the development of microprocessors would lead to the creation of compact affordable, personal computer that would someday supplant the bulky mainframe systems used in business and industry.

Meanwhile, Gates continued to excel in his studies and followed his parents’ wishes by going to Harvard. Paul Allen soon moved to Boston to work for Honeywell and continue their collaboration. The pair were galvanized by a cover story in Popular Electronics, promoting the Altair 8800, an inexpensive microcomputer produced by a company called MITS in Albuquerque, New Mexico. Gates and Allen saw this as the beginning of a new industry. No one had yet developed software for the Altair, and the young programmers saw a unique opportunity. They adapted the computer language BASIC to run on the new device, although they had never actually seen one. On the strength of this programming feat, they secured a software development contract with MITS. With irresistible business opportunities beckoning, Gates left Harvard at the beginning of his junior year to make the leap into the world of business. Along with Paul Allen, he moved to New Mexico at the end of 1975 to produce software for MITS. The following year, they started their own company, Microsoft.

After MITS was sold, Gates moved Microsoft to Bellevue, Washington, near his hometown of Seattle, a choice that would make the Pacific Northwest a center of the computer software industry. The Altair, along with personal computers produced by Atari, Commodore, and other industry pioneers, enjoyed popularity with hobbyists and computer aficionados, but had not achieved a comparable success with business or the general public, a vast untapped market. The dominant player in the computer industry, IBM, had long resisted the concept of the personal computer, because mainframe systems were the heart of its business. When IBM finally decided to make the move into manufacturing personal computers in 1980, it turned to Gates and Microsoft to produce an operating system.

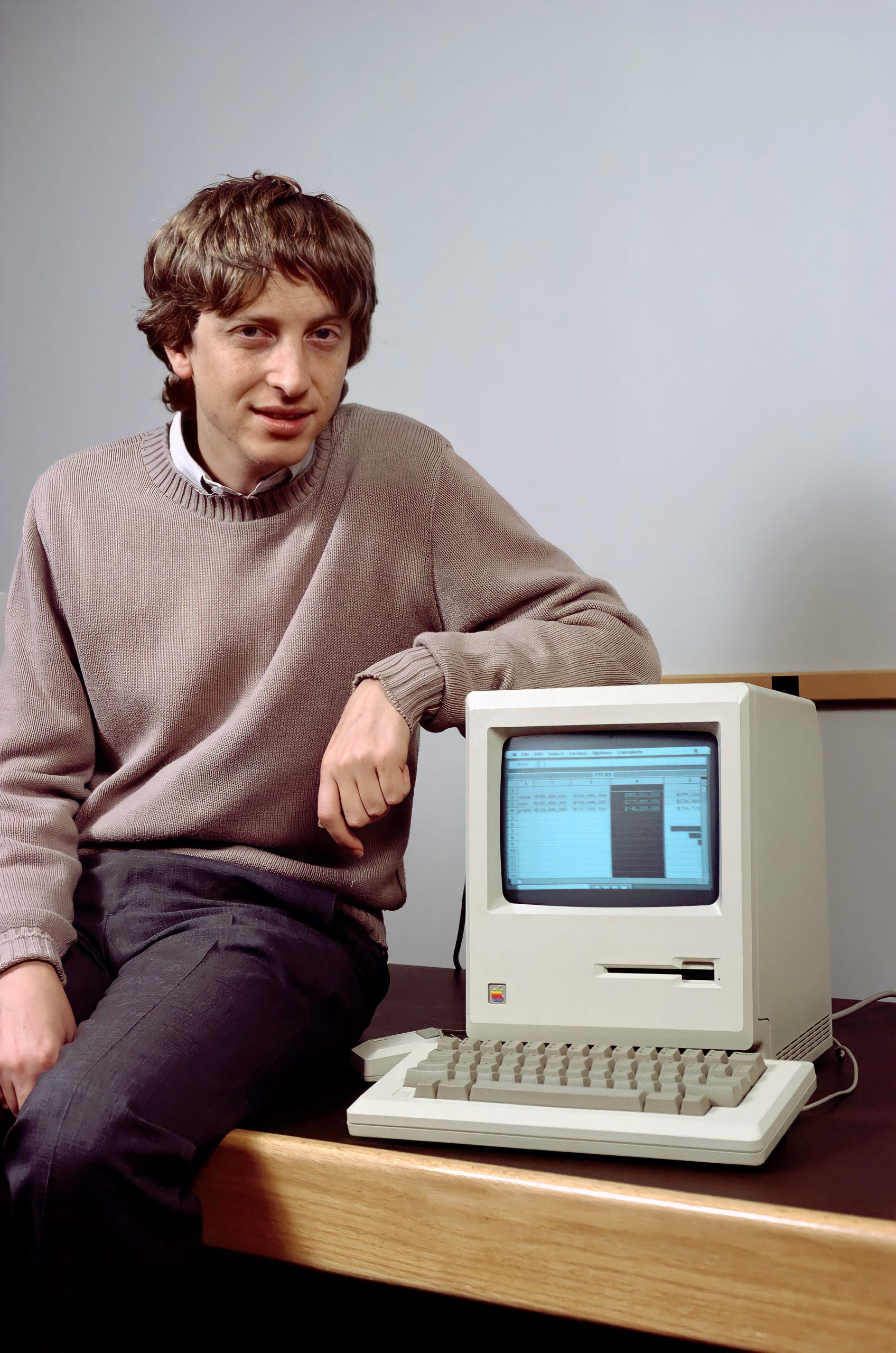

Gates bought an existing program, QDOS, and adapted it to the IBM hardware. He named his program Microsoft Disk Operating System, or MS-DOS. In his agreement with IBM, Gates was careful to retain the right to license MS-DOS to other hardware manufacturers as well. This may have been the single most momentous decision in business history. When the IBM PC became a success, other manufacturers rushed to create less expensive DOS-based personal computers. Microsoft’s operating system became the universal standard as personal computer use exploded around the world. The only noteworthy competitor in personal computer operating systems, Apple, had made the opposite decision; the Macintosh operating system could only run on Apple Macintosh computers, and Apple never gained more than a fraction of the worldwide desktop computer market.

Apple’s one advantage appeared to be the ease of use of its graphic user interface, but Microsoft quickly met that challenge with the 1985 introduction of Windows, a DOS-based graphic interface. With most of the world’s personal computers running MS-DOS and Windows, Gates had a perfect market for compatible software applications. Within a few years the applications in Microsoft’s office suite had become the leaders in their respective categories: Microsoft Word for word processing, Excel for creating spreadsheets, PowerPoint for slideshow-style graphic presentation, and Internet Explorer for browsing the increasingly popular World Wide Web.

In 1989, Gates founded Corbis, a digital image licensing company that acquired historic collections of photographs, such as the Bettmann Archive. Among other business interests, he has served as a director of the investment company Berkshire Hathaway and holds a controlling interest in a private investment firm and holding company, Cascade Investments LLC.

Meanwhile, the personal computer — and Microsoft software — revolutionized the worlds of work and recreation. Microsoft became an enormous international corporation, and by 1995, its Chairman, CEO and largest shareholder, Bill Gates, was the world’s richest man, a title he has retained almost every year since. By 2018, Bill Gates had amassed a personal fortune of $91.1 billion.

There were challenges along the way — a patent infringement suit from Apple over the design of the Windows interface, and a 1988 anti-trust suit brought by the United States government when it appeared that Microsoft’s dominant position in the industry had become a virtual monopoly. Microsoft survived these legal battles, and remains the preeminent producer of software for the home and office.

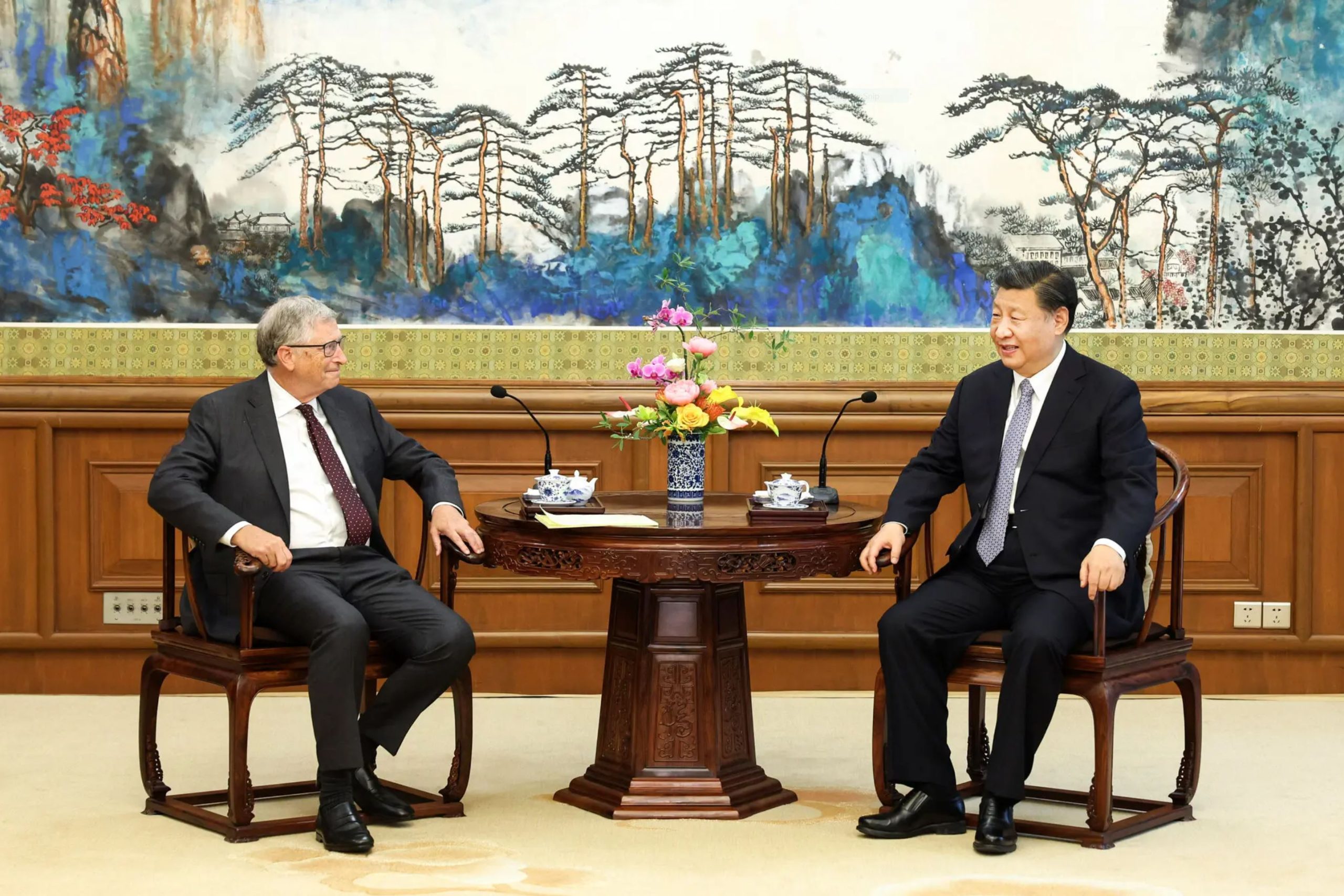

In 1994 Bill Gates married the former Melinda French. The couple built a technologically advanced house overlooking Lake Washington. They have three children. At the height of his success, Gates turned his attention from business to philanthropy. In 2000, he and his wife founded the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, and have given over $28 billion to charities focused on scientific research and international development. The same year, Bill Gates stepped down as Chief Executive Officer of Microsoft, though he remained Chairman of the Board of Directors. Since 2008, he has devoted his energies to the direction of the Gates Foundation, applying his entrepreneurial expertise to combating disease and poverty around the world. Through the Foundation’s efforts, half a billion children have been immunized since 2000, saving the lives of as many as seven million who might otherwise have died of infectious diseases.

In 2016, the contributions of Bill and Melinda Gates to business, information technology, and international philanthropy were recognized with the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor. The presidential awards citation read, in part, “From helping women and girls lift themselves and their families out of poverty, to empowering young minds across America, they have transformed countless lives with their generosity and innovation. Bill and Melinda Gates continue to inspire us with their impatient optimism, that together, we can remake the world as it should be.”

A rise in the price of shares in Amazon at the end of 2017 increased the wealth of that company’s founder and largest shareholder, Jeff Bezos, to the point where he surpassed Gates in net worth. But late in 2019, Microsoft signed a $10 billion contract with the U.S. Department of Defense to provide cloud storage for military data and technology — the Joint Enterprise Defense Infrastructure (JEDI). Shares in Microsoft increased in value over the news; they had gained nearly 48 percent over the course of the year. The Bloomberg Billionaire Index estimated Gates’s net worth at $110 billion, making him, for a time, once again the richest man on Earth.

The global pandemic of 2020 triggered another sharp increase in the value of tech stocks, including both Amazon and Microsoft, as well as Facebook and Google. As he continues to focus on the work of his foundation, Bill Gates has stepped away from his remaining business commitments.

He stepped down as chair of the Microsoft board in 2014, and in 2020 gave up his seats on the boards of both Microsoft and investment giant Berkshire Hathaway. In May 2021, Bill and Melinda Gates announced the end of their 27-year marriage, although they plan to continue their philanthropic work together.

In May 2024, Bill Gates had a net worth of $128 billion, primarily from his shares in Microsoft. Despite being nearly as wealthy as he had ever been, Gates ranked lower on the wealth index than he had since 1992 due to fierce competition at the top, a costly 2021 divorce, and his substantial charitable contributions totaling $59 billion. The Microsoft co-founder was the world’s richest person for 18 of the 23 years from 1995 to 2017.

In the last decades of the 20th century, a revolution in information technology transformed commerce and consciousness, just as the printing press transformed civilization 500 years before. These advances in computer technology and communications would have remained the province of professional scientists and mega-business if not for the introduction of the personal computer, and no person played a greater role in bringing the computer into homes and offices all over the world than William H. Gates, III.

Bill Gates was a teenage computer whiz when he dropped out of Harvard to start his own company, Microsoft. Through a brilliant combination of technical prowess and business insight, Gates made Microsoft the indispensable supplier of operating systems and office software to computer users around the world. If you use a computer to write a letter, compose an email or visit a website, chances are you’re using Microsoft software.

Microsoft’s uncontested dominance of the personal computer software market made Bill Gates the richest man in the world for many years. He has used his personal wealth to attack the most intractable global problems of disease and poverty through the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

You dropped out of Harvard in your junior year to start Microsoft with your friend Paul Allen. What was your original business plan?

Bill Gates: Microsoft was the first software company where we wrote software for personal computers. And we believed that we could hire the best engineers. There was an unbelievable amount of software to be written, and we could do it well and we could do it on a global basis. The original customer base was the hardware manufacturers. We sold to literally hundreds and hundreds, you know, over 100 companies in Japan, over 100 companies doing word processors and industrial control type things. We knew in the long run we wanted to sell software directly to users, but we actually didn’t get around to that until 1980, when we had our first sort of games and productivity software that people would go to a computer store and actually buy the software package.

When did you first have the vision of a computer on every desk at work and in every home?

Bill Gates: Paul Allen and I had used that phrase even before we wrote the BASIC for Microsoft.

We actually talked about it in an article in — I think 1977 was the first time it appears in print — where we say, “a computer on every desk and in every home…” and actually we said, “…running Microsoft software.” If we were just talking about the vision, we’d leave those last three words out. If we were talking an internal company discussion, we’d put those words in. It’s very hard to recall how crazy and wild that was, you know, “on every desk and in every home.” At the time, you have people who are very smart saying, “Why would somebody need a computer?” Even Ken Olsen, who had run this company Digital Equipment, who made the computer I grew up with, and that we admired both him and his company immensely, was saying that this seemed kind of a silly idea that people would want to have a computer.

![Altair 8800 Computer with 8 inch floppy disk system. Circa 1975. Photo taken at the Vintage Computer Festival 7.0 held at the Computer History Museum. November 2004. Description Altair 8800 Computer with 8 inch floppy disk system. Circuit boards - left to right Seals 8K Static RAM board MITS floppy disk controller (2 board set) MITS floppy disk controller MITS 16K Dynamic RAM board MITS 16K Dynamic RAM board MITS SIO-2 Dual serial port board Solid State Music PROM board MITS 8080 CPU board Photo taken at the Vintage Computer Festival 7.0 held at the Computer History Museum, Mountain View California. November 6-7, 2004 [1] This was one of Altair systems exhibited by Erik Klein [2] Photo by Michael Holley, November 7, 2004 Nikon E3200 with on camera flash. Touched up in Adobe Photoshop Elements 3.0. Date 7 November 2004 Source Transfered from en.wikipedia Author Swtpc6800 en:User:Swtpc6800 Michael Holley Permission (Reusing this file) Released into the public domain (by the author). Altair system owned Erik Klein Photo by Michael Holley License: Public Domain (wikipedia)](https://162.243.3.155/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/gat0-033-gates-Altair_8800_Computer.jpg)

When Microsoft was starting out, you guys made a deal with Apple Computer for a flat fee of $21,000 or something. What did you learn from that experience?

Bill Gates: Microsoft did the software for all the personal computers that came out. There was the Apple II that we did a BASIC for, which was called Apple Soft BASIC. There was a Commodore PET that we did a BASIC for. There was a Radio Shack TRS 80 that we did a BASIC for. Even Atari, who initially had their own mini-BASIC, ended up using our BASIC. So our BASIC was running on every single machine, including that Apple machine. We later did a BASIC for the Macintosh. We didn’t mind doing low priced contracts at the time, because we always knew that there would be new versions and more software that we would do. So it worked out well. As part of that Apple deal, I got to know Steve Wozniak, who is actually the engineer and did software programming, and Steve Jobs, who later I would do a lot of work with, because he was deeply involved in the Macintosh work.

Apple sold a lot of those computers — the Apple II. Wouldn’t you have made a lot more money at that time if you had royalties?

Bill Gates: Well, we had plenty of ways to do new versions and add-ons and things. So no, the whole structure of the way we licensed things was that we knew we could write software more efficiently than if they hired the engineers themselves. So we always were able to say, “Hey, you would have spent a half a million developing that yourself. We’ll license it to you for an inexpensive price.” We probably could have had higher prices, but we were doing fine. In fact, that 6502 BASIC that Mark Chamberlain and I wrote, we licensed to about 12 different people. So our profitability was huge, even though it was a great deal for Apple. Per machine they paid almost nothing.

You came out very early against illegal copying of software. You wrote a piece for Computer Notes, warning that piracy could create serious obstacles for your industry.

Bill Gates: Yeah. The MITS Altair people agreed to pay us a royalty for each copy that was sold. So if people paid MITS we got a royalty, and if they just copied the program — which was at the time on paper tape — we didn’t get paid. There was a lot of this going on, and the amount of piracy was going to determine whether Microsoft could hire more people or not. So I wrote — it wasn’t mean — what was called “An Open Letter to Hobbyists,” that said, “By the way, this is copyrighted material, and the more we sell, the more software we’ll be able to write.” And that started a debate that rages to this day, it will rage for decades to come. Should creative people who do music or books or software be able to get a royalty for their stuff, or should people pirate it? There’s a lot of complicated issues in intellectual property, but it started early in the computer industry. A lot of people did actually respond to the letter by coming back and paying the license fee, which was very low. I mean, everything was very, very cheap.

When IBM first came to you for an operating system, you sent them to another company, Digital Research, first. Why did you do that?

Bill Gates:I had been talking about our BASIC, and running that on a computer. There’s two ways you could run BASIC. You can run it where the BASIC is right on the hardware and the only thing you’re running is BASIC, or you can put another layer of software in between, called an operating system, and it can take over some of the work, like managing the printers and things, and you can have many programs, BASIC or a spreadsheet or a word processor, running on top of that. And as we got disks on these computers, it made more sense to have that flexibility. The early computers don’t have disks; they have cassette tapes and paper tapes and things like that. But by 1979, ’80, we’re starting to get these big, expensive — actually, initially eight-inch — floppy disks, then five-and-a-quarter inch, finally three-and-a-half inch. Now, when’s the last time you saw a floppy disk? But they were very important. We still have a hard disk, the disk built into the computer.

So you needed an operating system. When IBM saw that we had written the software for all the personal computers, they came to us, sought our advice on the design, but we said, “You should put a disk in,” and since they wanted to ship very quickly, another company called Digital Research had done that work for the 8-bit machines, and they were starting to do a version for these new 16-bit machines. We convinced IBM to do a 16-bit machine using this 8086, 8088 processor. Well, Digital Research really hadn’t finished the work, and then IBM was getting frustrated because Digital Research wouldn’t sign even the non-disclosure agreement, and then some of us, particularly Paul and a key person named Kazi Konishi, who was from Japan and worked with us, said, “No, no, no, we should just do that ourselves.” And because of the quick timing, we ended up licensing the original code from another company and turned that into MS-DOS. So then subsequently, MS-DOS competed with this Digital Research CPM. After about two or three years, MS-DOS became far, far more popular than CPM, and then eventually we would take and add graphics capability on top of MS-DOS, and then integrate the two together. And so today when we talk about Windows, it actually includes all those MS-DOS things in it, that’s the full operating system. Although mostly you think of the graphics and the windows and stuff, there’s a lot of more classic operating system capability that’s built in there.

Did you get a royalty from IBM for each computer they sold with MS-DOS?

Bill Gates: Actually, no.

The IBM initial deal is a flat fee deal, another flat fee deal. It had certain restrictions that prevented IBM from selling to other hardware makers. So if people did IBM PC compatible machines, we would get the revenue by doing business directly with those people. And the deal was very complicated, but it was a deal that Steve Ballmer — who’s a key person with the company by that time — and I thought a lot about. It was a fairly junior team from IBM, so we tried to make sure that — given our belief that personal computers would be hyper-popular — that Microsoft would get a lot of that upside.

So they felt they got a very good deal, which they did, but as the industry expanded, we — for new versions and for different machines — we got that opportunity, even though they did not pay us a royalty.

When did you realize just how wildly successful this business would be?

Bill Gates: Even in the early days, if you set a computer on every desk in every home, and you’d say, “Okay, how many homes are there in the world? How many desks are there in the world? Can I make $20 for every home, $20 for every desk?” you could get these big numbers. But part of the beauty of the whole thing was we were very focused on the here and now. Should we hire one more person? If our customers didn’t pay us, would we have enough cash to meet the payroll? We really were very practical about that next thing, and so involved in the deep engineering that we didn’t get ahead of ourselves. We never thought how big we’d be. I remember when one of the early lists of wealthy people came out and one of the Intel founders was there, the guy that ran Wang computers actually was still — Wang was still doing well — and we thought, “Hmm. Boy, if the software business does well, the value of Microsoft could be similar to that.” But it wasn’t a real focus. The everyday activity of just doing great software drew us in. And some decisions we made — like the quality of the people, the way we were very global, the vision of how we thought about software — that was very long term. But other than those things, we just came into work every day and wrote more code and hired more people. It wasn’t really until the IBM PC succeeded, and perhaps even until Windows succeeded, that there was a broad awareness that Microsoft was very unique as a software company, and that these other companies had been one-product companies, hadn’t hired people, couldn’t do a broad set of things, didn’t renew their excellence, didn’t do research. So we thought we were doing something very unique, but it was easily not until 1995, or even 1997, that there was this wide recognition that we were the company that had revolutionized software.