I realize there just are no permanent victories. You have to keep fighting for freedom. There is always an impulse to degrade people who are different from you, to diminish them, to demean them and it never seems to go away, even when there is ample evidence that when we work together, we do better.

The 42nd President of the United States was born William Jefferson Blythe III, in Hope, Arkansas. Three months before his birth, his father, William Jefferson Blythe, Jr., was killed in a car accident. His mother, Virginia Cassidy, left him with her parents in Hope while she went to nursing school. When her child was four, Virginia Cassidy married Roger Clinton, an automobile dealer. William, called Bill, moved with his mother and stepfather to Hot Springs, Arkansas and soon had a younger stepbrother, Roger Clinton, Jr. When he was 15, Bill officially changed his name to William Jefferson Clinton. All was not peaceful in the Clinton household. Roger Clinton, Sr. was an alcoholic with a violent temper, and on occasion, the teenage Bill had to intervene physically to prevent his stepfather from beating his mother and brother. Despite turmoil at home, Bill Clinton did well in school, taking a special interest in history, public speaking and music. Outgoing and gregarious, he threw himself into a wide variety of extracurricular activities. He sang in his church choir, played first saxophone in the state youth band, and joined the American Legion Boys Nation program.

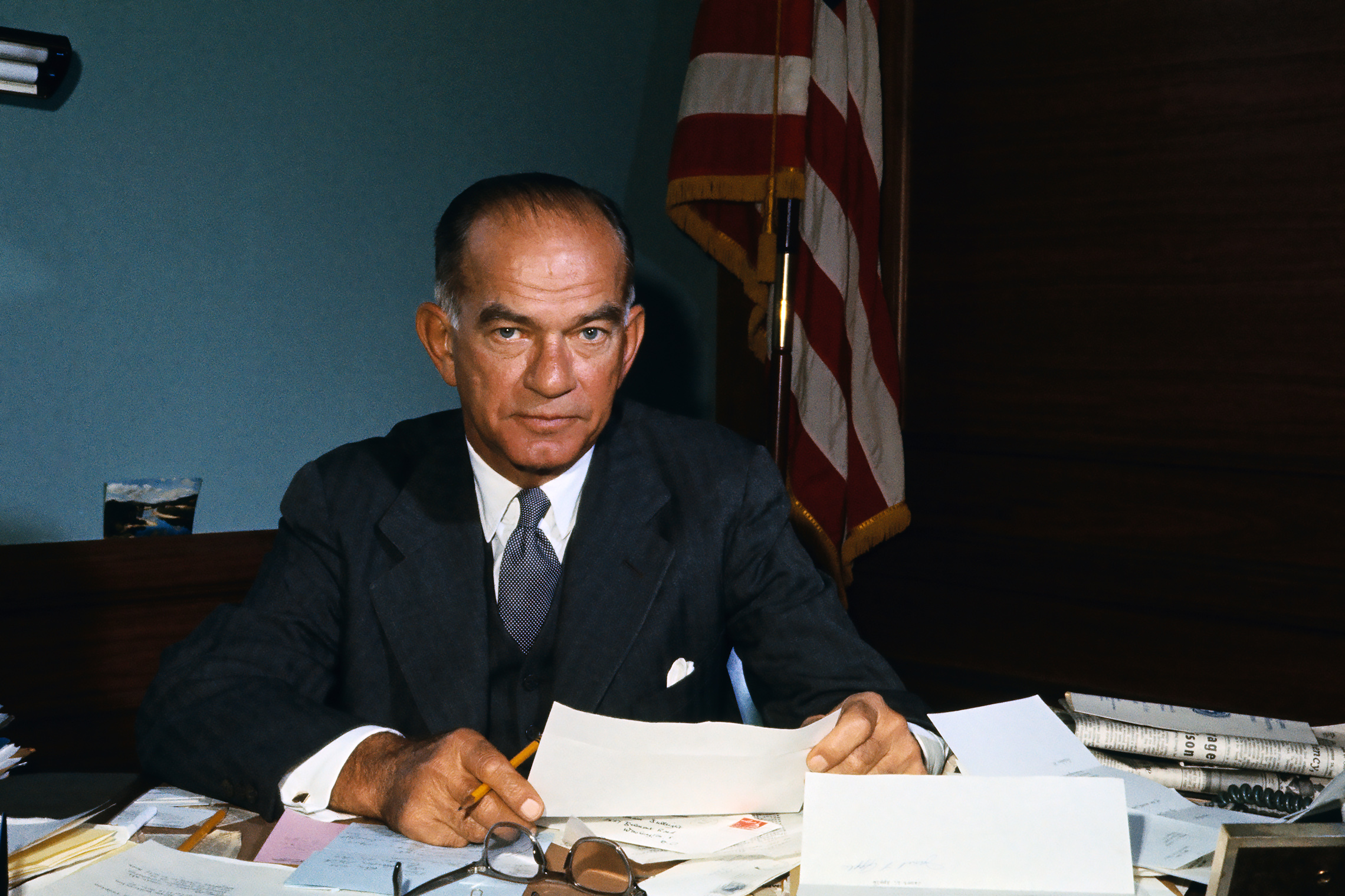

President John F. Kennedy was one of Clinton’s boyhood heroes, along with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., whose “I Have a Dream” speech he memorized after seeing Dr. King on television. In 1963, Clinton was one of two boys elected to represent Arkansas in a Boys Nation mock-Senate session in Washington, D.C. At the time, President Kennedy’s proposed Civil Rights Act was stalled in the Senate. In their deliberations, the Boys Nation assembly passed the measure. President Kennedy invited the boys to the White House, and the 16-year-old Bill Clinton was thrilled to be photographed shaking hands with the president. Increasingly interested in a career in public service, Clinton volunteered for political campaigns in Arkansas. He won scholarships to the School of Foreign Service at Georgetown University and entered the university in the autumn of 1964. Professor Carroll Quigley’s course “The History of Civilizations” made a great impression on Clinton, with its emphasis on the Western ideal of progress. Another powerful influence on the young Clinton was the U.S. senator from Arkansas, J. William Fulbright. While he was attending Georgetown, Clinton secured a part-time position in Senator Fulbright’s Washington office. Although Clinton disagreed with Fulbright’s opposition to the Civil Rights Act, he was impressed by the senator’s courage in investigating the progress of the Vietnam War, a decision that brought the senator into conflict with the leader of his own party, President Lyndon Johnson.

A longtime advocate of international educational exchange, and founder of the Fulbright Scholar Program, Senator Fulbright had studied at Oxford as a Rhodes Scholar. As graduation from Georgetown approached, Clinton too applied for a Rhodes Scholarship and — largely on the basis of his work for Senator Fulbright — was accepted. Traveling to England by ocean liner, he met a fellow Rhodes Scholar, Robert Reich, who would later serve as Secretary of Labor in the Clinton administration. Clinton studied politics, philosophy, and economics at Oxford, but left without taking a degree, returning to the United States to attend Yale Law School. At Yale, he met a fellow law student from Illinois who was one of the few women in the program, Hillary Rodham. Many of her classmates expected her to pursue a career in public service in New York or Washington and were surprised when she chose to join Bill Clinton in Arkansas. Both taught at the University of Arkansas Law School in Fayetteville, while Bill Clinton made his first try for public office, running for Congress. Although he was defeated by the Republican incumbent, Clinton made a stronger run than previous Democratic challengers. The couple was married in 1975. The following year, Bill Clinton was elected Attorney General of Arkansas; at age 30 he was the youngest attorney general in the country. Clinton made national news in 1978 when he was elected governor of Arkansas.

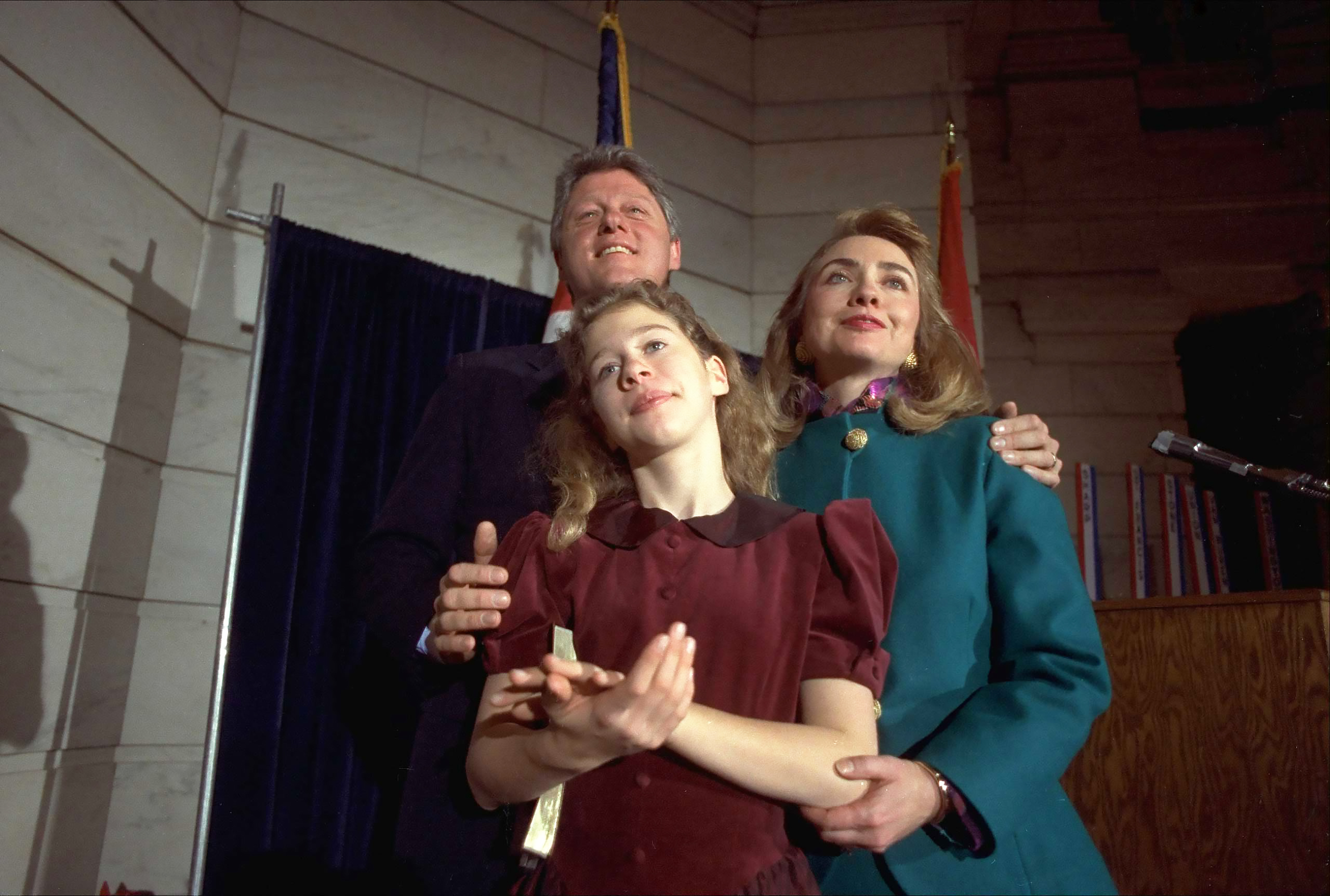

The Clintons’ only child, Chelsea, was born during their first term in the governor’s mansion. At the time, the Arkansas constitution set the limit of a governor’s term at two years, and after signing an increase to the state’s motor vehicles tax to cover a budget shortfall, in 1980 Clinton was defeated for re-election. But in 1982, he was re-elected and would hold the office for the next ten years. After Clinton was elected to his third two-year term, Arkansas extended the term of its governors to four years. Clinton was elected to four-year terms in 1986 and 1990.

The signature accomplishment of Clinton’s governorship was a sweeping series of educational reforms. His administration raised the state’s sales tax to pay for increased spending on education. Clinton expanded both vocational training and programs for gifted students, and raised standards of instruction, with augmented compensation and compulsory competency exams for teachers. Improved education results in Arkansas and Clinton’s chairmanship of the National Governors Association made him a national figure and presidential prospect.

At the beginning of the 1992 campaign, incumbent President George H.W. Bush was considered unbeatable, but a faltering economy eroded his popularity, while a compromise with the Democratic Congress on taxes created dissension in Republican ranks. A third party challenge by businessman Ross Perot further complicated the playing field. Clinton’s candidacy for the Democratic nomination was nearly derailed by allegations of marital infidelity, but the governor’s appearance with his wife on prime time television revived his candidacy. Clinton’s victory in the New York primary made him the clear front-runner for his party’s nomination. His selection of a fellow young Southern moderate — Senator Albert Gore, Jr., of Tennessee — as a running mate reinforced the sense of a generational shift in American politics, and Clinton emerged from the Democratic Convention as the leader of a united party.

After strong performances in televised debates, Clinton was swept to victory along with Democratic majorities in both houses of Congress. In his first year in office, Clinton succeeded in passing a budget which included a tax cut for lower-income Americans and a tax increase on higher incomes. The dissolution of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War permitted a substantial reduction in military spending, and with the economy recovering, the next few years saw a gradual reduction in the federal government’s annual deficit. Although Clinton’s 1993 budget received no votes from congressional Republicans, he assembled a bipartisan coalition to enact the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), with more Republicans than Democrats voting in favor of the agreement.

In his first term, the president achieved notable foreign policy successes, hosting Israel’s Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin and Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat for the historic signing of the Oslo Accords in 1993. The following year, Israel and Jordan signed a peace treaty in a White House ceremony.

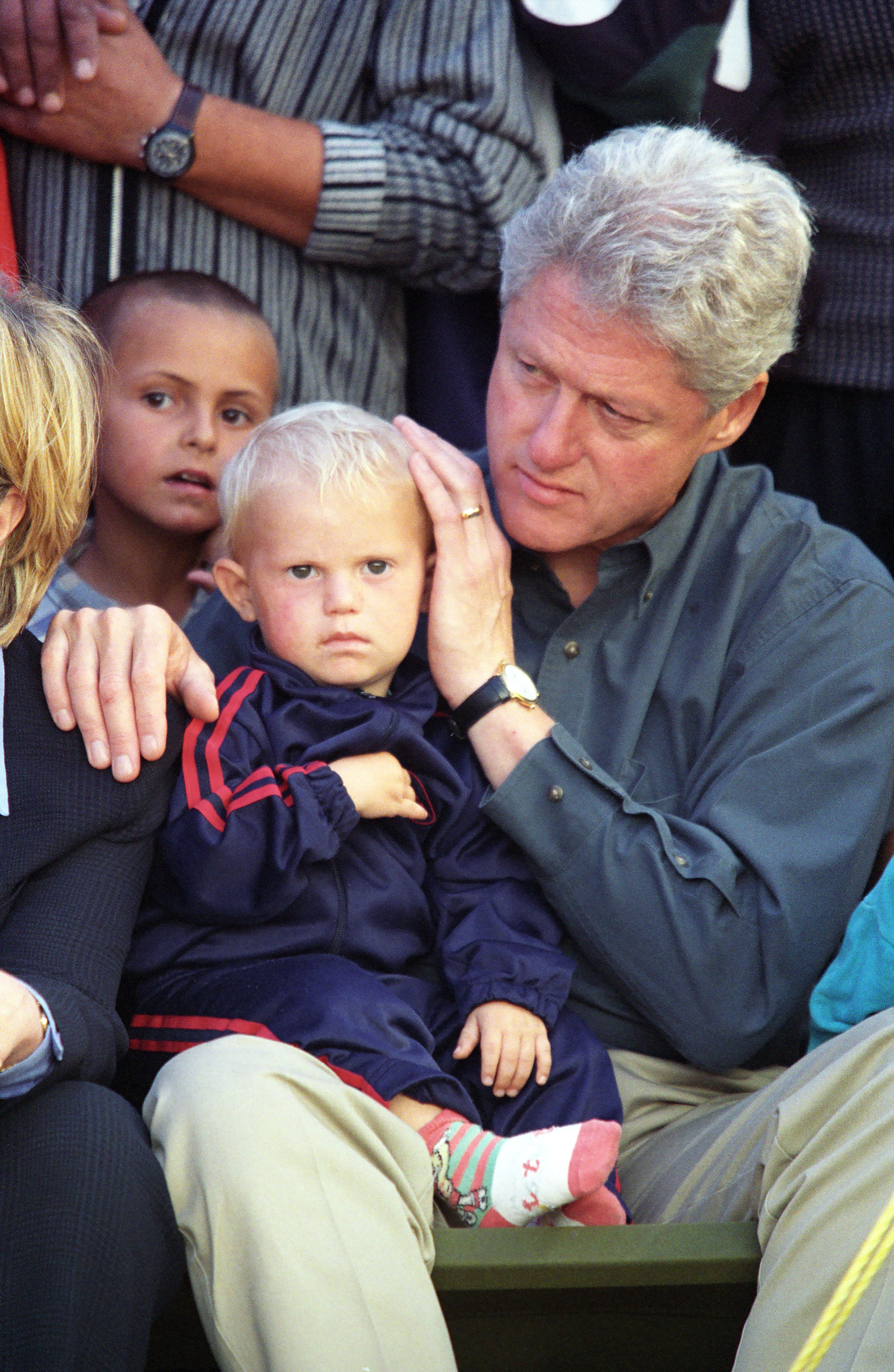

In 1995, Clinton mobilized NATO allies to carry out air strikes against Bosnian Serb forces in Bosnia-Herzegovina, forcing the combatants to the negotiating table. Clinton dispatched U.S. troops to keep the peace in Bosnia after the completion of the Dayton Agreement. Clinton led a second NATO intervention in the Balkans in 1999, to avert a massacre of the Muslim population of Serbia’s Kosovo region. Subsequent negotiations led to the independence of Kosovo.

His ambitious plan to reform the nation’s health insurance system failed in Congress, and in the 1994 elections, the Democratic Party lost control of both houses of Congress for the first time in 40 years. Clinton sought bipartisan compromises with the Republican Congress, enacting a welfare reform bill that antagonized many members of his own party. Bipartisan measures deregulating the financial services industry, passed toward the end of his second term, were widely supported at the time. Critics have subsequently suggested that they contributed to the financial crisis of 2008, many years after President Clinton left office, although the former president disputes this analysis.

President Clinton broke with the policy of previous administrations with regard to Britain’s troubled rule over Northern Ireland. Over the objections of the British government and against the counsel of his own advisers, he issued a visa to Sinn Fein leader Gerry Adams and received him at the White House. The Irish nationalist party responded with major concessions and Clinton successfully pressured longtime enemies to enter peace talks. These talks led to the Good Friday Peace Accord, negotiated by former Senate Majority Leader George Mitchell, with Northern Ireland’s Unionist leader David Trimble and Social Democratic Labour Party leader John Hume. The accord ended decades of violent conflict in Northern Ireland, and all parties to the process give a measure of credit for its success to the president’s sustained personal involvement in the process.

At the outset of the Clinton administration, the Internet and the World Wide Web were virtually unknown to most Americans. His administration supported construction of the fiber optic networks that enabled the expansion of broadband Internet service — the “information superhighway” he had described to widespread incomprehension in his 1992 presidential campaign. Along with Vice President Gore— an early Internet advocate — he pressed all government departments to adopt the new technology. By the time he left office, the Internet had become a ubiquitous presence in American life.

Clinton won re-election to the presidency in 1996, although Republicans retained control of Congress for the rest of his term. As early as 1994, an independent counsel had been appointed to investigate the Clintons’ financial dealings in Arkansas. The investigation failed to find any proof of financial crime but uncovered an improper relationship between the president and a young White House aide. Clinton had already denied having a sexual relationship with the aide during a sworn deposition in an unrelated case. The matter was referred to the House of Representatives, and in 1998 the House voted to impeach the president for perjury and obstruction of justice. For the second time in history, a president stood trial before the United States Senate. As the nation watched on live television, Clinton was acquitted of all charges.

Although the country remained passionately divided over the case, the president’s popularity increased following the impeachment trial. After 30 years of budget deficits, the federal government recorded budget surpluses for the last three years of his presidency, and President Clinton left office with the highest approval ratings of any departing president since World War II.

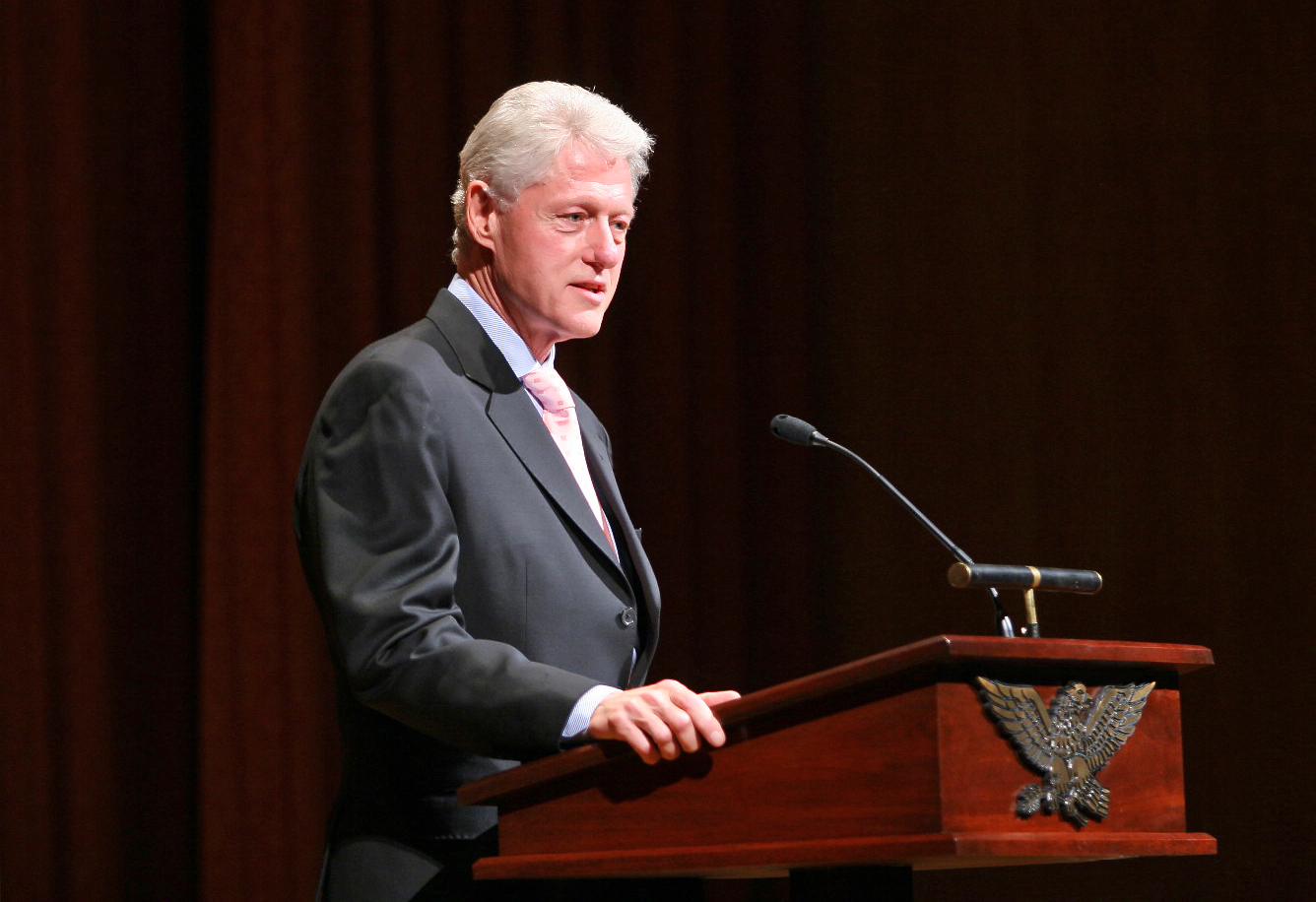

In the years since his presidency, Bill Clinton has achieved enormous success as a public speaker and wrote a bestselling autobiography, My Life. He founded the Clinton Foundation to address global causes such as the AIDS epidemic and climate change. The foundation has achieved considerable success in promoting public health in underdeveloped countries and has received high ratings from charity rating organizations for spending the largest part of its contributions directly on its programs and a bare minimum on administration or fundraising. After leaving office, President Clinton forged a surprising friendship with his former election rival, President George H.W. Bush, and worked with former President George W. Bush on Haitian earthquake relief. Clinton was also a highly visible advocate for the political campaigns of his wife, Hillary — who was elected to the U.S. Senate from New York in 2000 — and for President Barack Obama.

Despite the partisan conflicts that raged throughout his tenure, and lingering controversy over his personal conduct, the eight years of his presidency were years of unparalleled economic growth, which saw a temporary reversal in a decades-long trend toward income inequality. Public opinion polls registered a high level of approval of Clinton’s presidency for many years following his departure from office.

During the administration of William Jefferson Clinton, the United States enjoyed more peace and economic well-being than at any time in its history. Prior to his election as president, Bill Clinton served five consecutive terms as Governor of Arkansas, a position to which he was first elected at the age of 32. He was the first Democratic president since Franklin Roosevelt to be elected to two full terms in office.

In foreign affairs, he helped bring about the historic peace accord between Israel and Jordan, and facilitated an unprecedented degree of cooperation between Israel and the Palestinians. His influence also helped promote the peace process in Northern Ireland. President Clinton dispatched American military troops to enforce agreements restoring the democratically elected government in Haiti, ending the civil war in Bosnia, and averting imminent genocide in Kosovo. On his orders, American military power was also used to disrupt terrorist activities in Sudan and Afghanistan.

Throughout the course of the Clinton administration, the United States moved from record deficits to record surpluses, enjoyed the lowest unemployment rate in modern times, the lowest inflation in 30 years, plummeting crime rates, and the highest home ownership rate in history — the strongest economy in a generation and the longest economic expansion in U.S. history.

When you accepted the Democratic nomination for president at the 1992 convention, you mentioned a favorite professor you had met at Georgetown, Carroll Quigley. How was he important to you?

Bill Clinton: Let me just say a word about Georgetown. I think it’s unlikely I would have been president if I’d never gone there. That’s how important it was to me. When I wrote my autobiography my editor made me take out 20 pages that I wrote about Georgetown, and there’s still about 20 in there. He said, “It’s impossible you remember all these teachers and all the questions on the exam there,” and I said, “No, it’s not. You have no idea.” For me, it was like the world was opened to me.

So Quigley taught a course called “The History of Civilizations,” and at the end, he said that the great gift of Western civilization to the human race was the idea of progress in a very specific way. He said it was the idea that the future can be better than the present and that every single person, not just the rulers, not just the elected leaders, not just the billionaires, every person has a personal moral obligation to make it so, to keep it going, to make the future better. And it resonated with me. I thought, “That’s the purpose of politics.” It made me really think even more than I had before that I might like a career in public service.

It also made me aware of why in the aftermath of something like the 2008 crash you are going to have so much disorientation and anger and frustration because too many people have gotten up every day, and some still do, and looked in the mirror and thought all their tomorrows were going to be like yesterday.

It’s the ultimate disempowerment. There’s nothing you can do for yourself, and even worse, for your family. It’s going to be all the same, and Quigley made us understand that our whole culture in Western civilization was designed to counter that, to believe that you personally could make a difference, and I never got over it. I still think about it. You’d be amazed. I still think about it. I think about a lot of things I learned in college, but that was very important for me.

While you were at Georgetown, you clerked at the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, headed by Senator Fulbright of Arkansas. How did that experience shape you?

Bill Clinton: I got the job because I needed the work. I needed the money. My stepfather got sick when I was at Georgetown, and I was afraid my family didn’t have enough money for me to stay, and so I needed to go to work, and Senator Fulbright’s chief of staff was close to a man that I had worked with. By then I was working campaigns and stuff in Arkansas, and he called me one day, woke me up out of a cold sleep, and said, “You can come here.” He said, “You can have a part-time job for $3,500 a year or,” he said, “you can work full-time” — and some people did and went to school at night — “for $5,000 a year.” And I was still groggy, and I said, “I would like two part-time jobs.” He said, “You’re just the guy I’m looking for. Be here Monday morning.” I’ll never forget it. It was Thursday morning. So I started packing, gassed up the car, got in on Saturday and drove up and showed up for work Monday.

My job was basically to be a delivery boy for all kinds of things, but they also — because I was at Georgetown and studying international affairs, I was assigned to read six newspapers a day and clip the most relevant articles. This is the technology we used. You couldn’t scan articles. There was no “online.” There was nothing, right? So I would read the newspapers, clip the articles I thought they ought to read, put them on a routing slip, which had on it the names of the senior staff of the committee and all the senators who were committee members. And I would send it to the senior staff, and they would decide whether to send any of them on, but I don’t think I’d have won a Rhodes Scholarship if I hadn’t been a clerk on the Foreign Relations Committee. Nobody else I was competing with read six newspapers a day, and they actually paid me good money to read The Washington Post, The New York Times, The Washington Star, which existed then, The Baltimore Sun, The St. Louis Post Dispatch, and then we alternated — and — oh, and The Wall Street Journal. We read them every day. Those were the six papers we read. I did, and then that’s what the senators got.

Bill Clinton: The Vietnam War hearings were going on. The Senate Foreign Relations Committee conducted these very serious hearings, and Senator Fulbright, the chairman, was opposed to our policy; and Dean Rusk, Secretary of State, was the spokesperson for it — President Johnson’s secretary of state. And I never will forget, I learned a lot about how Washington worked because on the days the committee was going to have a hearing, quite often Rusk would come in, 7:30 or 8:00 in the morning, and drink coffee with Fulbright to prepare for the hearings, knowing they were going to fight like cats and dogs. It was a different time. They still could be civil to each other, could listen to one another. And they — Fulbright didn’t want there to be any surprises in the hearings. He didn’t mind them knowing, you know, what they were going to ask about, who was particularly interested in this, that, or the other thing. It was fascinating. We brought in all these experts.

I loved it, and I learned so much. I also had to have a security clearance just to carry documents that were marked “secret” or “classified.” And I started my long education in the ins and outs of the classification system of the United States government when I was an undergraduate. And because Fulbright was the chairman of the committee he had an automated — some sort of automated device that allowed the Pentagon to send him, every day, a list of the people who’d been killed in Vietnam from Arkansas. So I would go check it every day. Four of my high school classmates were killed, including, as I said, the son of my guy who was my Sunday school teacher for nine years. And I also knew, because I had to carry the stuff around, that not everything the government was claiming about the progress on the battlefield was true, and it’s kind of a crazy burden for a kid my age. I felt guilty I wasn’t there, and it felt futile to go. It was an awful feeling.

Senator Fulbright was quite outspoken in his opposition to the war. How did that impress you?

Bill Clinton: He knew that it would be unpopular in Arkansas. You know, we’re just a state dominated by the Scotch-Irish, who provided 25 percent of all the soldiers who ever fought in uniform for America since the revolution. One of our counties had the highest fatality rate of any county in America in World War II. A lot of poor African American kids were in the military, and their parents didn’t want to know it was for nothing.

I mean it was like an across-the-board challenge, and he believed — he had a very clear view of it, and I thought it was unusual because Fulbright had been more willing than I wish he had been to trim his sails on civil rights for a long time. And he said, “Yes, I disagree with them on that too,” but he said, “If you want to be a representative, and they know something, as much about something as you do — and they do on this — sometimes you have to give in.”

“But on this, if I know more than they do, I am doing an immoral thing to preserve my political position at the expense of doing what’s right for their children over the long run.” And in the end, it played a significant role in the undoing of his career, but he did an enormous service to the country in the meantime. And I think — he lived to be 87 — he lived long enough for me to become president and give him the Medal of Freedom, and I think he died at peace with himself and the decision he made.

Looking back on your presidency with the hindsight of history, can you talk about some of the decisions people are still debating, such as welfare reform?

Bill Clinton: If I had to make the welfare decision again tomorrow, I’d sign it again tomorrow. We had a 60 percent reduction in the welfare rolls. We had an enormous percentage of poor people move into the workforce, start middle-class lifestyles, and when we had a brief tech recession of six months in 2001, after I left office, people who had moved from welfare to work were less likely to be laid off than the general working population. So I would do it again.

Now I did not foresee that we would move so far to the right as a country, mostly because Democrats started winning the popular vote in presidential elections, and so a lot of them just don’t vote at midterm when the governors, the state legislatures, and the congressional districts are decided.

If somebody told me that eight states would abolish cash benefits altogether I guess I’d have had to rethink it, but since the ‘70s there was no minimum welfare benefit. You just couldn’t go below where you’d been on the date certain. So, for example, when I signed welfare reform, a poor family of three on welfare got $655 a month in Vermont. They had the highest benefits, and $183 a month in Mississippi, Texas, and one other place. In other words, I think people had this idea that there was some national welfare system. There wasn’t. The national welfare system was, everybody gets Medicaid for their kids, and you get food assistance. The Republicans tried to get rid of that, and I vetoed those first two bills because I wouldn’t do that.

I knew what would happen then, that a lot of people would be in trouble, but I didn’t foresee that they’d get rid of that altogether. Also, the law, as written, said that states will continue to get, no matter how small the welfare rolls get, the same amount of money they got in February of ‘94 when the welfare rolls hit an all-time high. After I left office that requirement was not enforced.

So the real question is: Should every president walk around thinking, “No matter how good this bill is, I should think of the worst-case scenario, and if anything bad might ever happen after three more elections occur, I shouldn’t ever sign a bill.”? I don’t think you can do that.

What about the North American Free Trade Agreement — NAFTA?

If I hadn’t signed NAFTA it would have been worse. First of all, I made it better. We got more environmental protections, and we developed something called the North American Development Bank to promote more investment, particularly near the border where jobs were lost.

Secondly, if I hadn’t signed it — after the Mexicans and the Canadians thought, under President Bush before me, it would be the law and they had reached agreement — we would have had more undocumented people pouring in from Mexico. We would have had more drugs coming in from Mexico, and everybody in Latin America would have hated our guts for walking away from our future.

Now, what did I learn from it? I learned that there were people, mostly in the other party, who believe in free trade but didn’t really believe in doing anything for people who lost jobs. That is, every trade deal produces winners and losers, so this was going to work for us in a lot of ways because the Mexicans had much higher tariffs than we did. And because, if you’re a wealthy country, the jobs trade creates pay above the average wage, and often the jobs that are lost pay below.

But it’s always assumed that all those people will be retrained and that there will be incentives to invest within driving distance of where they live to create new jobs. And we lost the Congress in ‘94, and I couldn’t get the money, and there was no interest in it until my last year as president when we passed something called the New Markets Initiative. So if I had it to do again, I’d get the money on the front end, and I’d say, “No, no, no, no. I need more money to help the people who will lose the jobs.”

I just assumed, I think probably because I had — the Congress was the majority of our party, and also because the people that were for NAFTA, I couldn’t imagine that they wouldn’t want to help the people that wouldn’t be winners.

What do you think now about the decision to remove the Glass-Steagall restrictions that separated investment banking from commercial banking operations? Some people think that contributed to the 2008 financial crisis.

I don’t think the Glass-Steagall bill made any contribution to the financial crisis at all for a simple reason. The difference in investment banks and commercial banks had been abolished in the 1980s by rulings of the Federal Reserve. So the main practical impact of my signing that bill was to allow banks to offer certain kinds of insurance, which played no role in the financial crisis. That wasn’t a big problem.

There was another bill that I think did make a contribution to the crash that I wish I had vetoed for symbolic reasons. They would have overturned my veto. And that was a bill that allowed banks to engage in all these derivatives, like collateralized debt obligations, without sufficient collateral. Now, it passed overwhelmingly. Almost every Democrat voted for it, and we all wanted it because it reauthorized something I’ll call the Community Reinvestment Act. The Community Reinvestment Act, if the government enforces it, requires every bank in America to reinvest some money where they take deposits.

And we’ve got 800 billion dollars of investment under it when I was president. Ninety-six percent of all the money that had ever been invested under it, going back to the 1970s, was in those eight years. See, it was a goldmine of broad-based prosperity, and I wanted it badly, and a lot of other Democrats did, and we voted for it, but it would have been overridden, the veto.

And I wish I had vetoed it because I never believed — I had a big argument with Alan Greenspan. He said, “But these things only affect investors with 100 million dollars or more. They can take care of themselves.” I said, “Yeah, I don’t care if they lose 100 million, but you don’t understand. If 100 of them lose 100 million, or 1,000 of them lose 100 million, it can wreck the whole rest of the economy,” which is essentially what happened in the housing crisis. So I wish — it would have become law anyway. I wish I had vetoed that and sounded the alarm.

What are you most proud of having accomplished as President of the United States?

Bill Clinton: I’m most proud of the fact that we produced broad-based prosperity, where the incomes of the bottom 20% rose more percentage-wise than the incomes of the top 20%, about the same as the incomes of the top 5%. That was across all racial groups, all regional groups, and all income groups, and that we did it while eliminating 600 billion dollars in national debt. And I put America on a path to be debt free so that we’d be able to embrace the challenges of the 21st century, and I think that at a time of yawning inequality, having inclusive prosperity is very important to building support for inclusive societies. I’m very proud of the fact that we did it together, that there was — you know, I had the most diverse administration ever then, and we proved it, and they were good. Everybody was good at what they did. We all worked together, and we proved that diverse groups make better decisions than homogenous ones or lone geniuses. I’m proud of that, and lots of other things we did I’m proud of, but I would — I think it worked for ordinary people, the people that were paying the bill, the people that needed help, the people whose incomes went down in the 1980s, and I think it can be that way again.

I think we’re in a better position as a nation for the 21st century than any other major country, but if you want to take advantage of it you can’t fight all the time. You’ve got to cooperate. If you want to take advantage of it you have to see diversity as a massive asset. If you want to take advantage of it you can’t be anti-immigrant because the native-born population’s birthrate is static. And having lost it, I can tell you youth matters to the productivity of a country. Having a median age that’s fairly young matters. You can’t ignore the fact that immigrants are twice as likely to start businesses as the native-born, and that the crime rate among immigrants, including undocumented immigrants, is half that of the native-born. So to pretend this is some great criminal problem and a drag on the economy is the reverse of what is true. It may be good politics at a time when people are angry and looking for somebody to blame, but we need to make some decisions here about the definition of citizenship. What does it mean to be an American? What does it mean to have an American community? What are we going to do? But if you want it to work for everybody again, cooperation is a much better model than conflict. Conflict may work in certain election circumstances, but this country was built by “let’s make a deal.”